Displacement Inside and Outside: The Right to Remain in the Downtown Eastside

On March 6th, I attended the opening reception of The Right to Remain: A Creative Repossession of the Human Rights Legacies of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside at Gallery Gachet. Not being a resident of the Downtown Eastside, I went because I was invited by some of my friends who do.

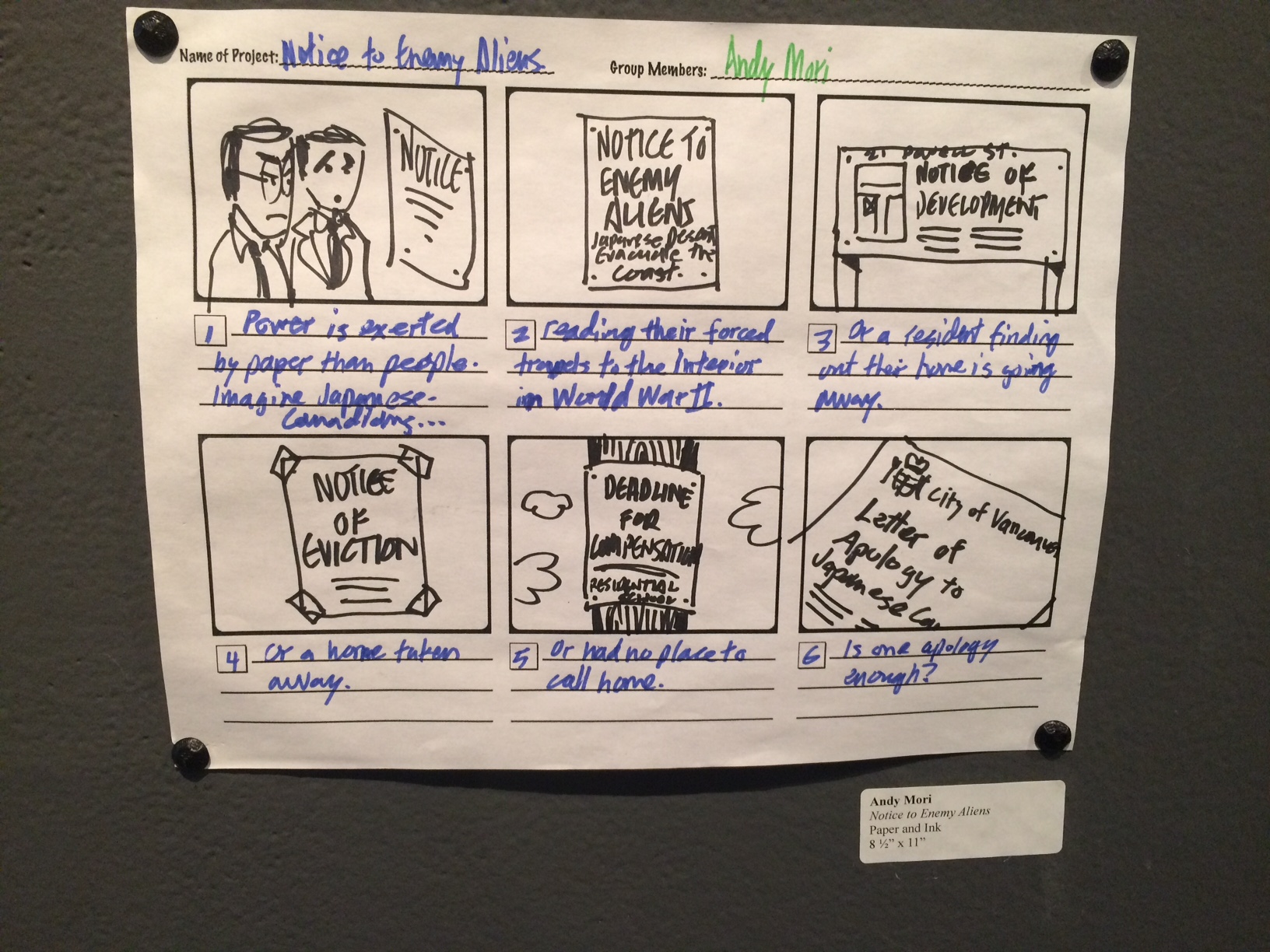

Gallery Gachet stands kitty-corner to Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre, on East Cordova, which is a block away from Powell Street. After Japanese Canadians were forcibly removed from their homes in Powell Street (and Steveston) during the Second World War, they return to find their properties sold—their lives doubly displaced.

Today, this racialized community’s history with displacement is a legacy the City of Vancouver continues to exploit and erase, by calling the encroaching wave of gentrification of the Downtown Eastside “Japantown,” and attempting to rebrand this low-income neighbourhood into a ‘Japanese’ village. As the first of two art exhibits coming out of the “Revitalizing Japantown?” research project, The Right to Remain aims to highlight community struggle and resilience against ongoing displacement, racism, and colonization. Implicit in this aim is to connect Japanese Canadians’ struggles for human rights inside and outside of Powell Street with the DTES community’s current struggle against gentrification, as they all take place in the context of ongoing colonial dispossession of Indigenous lands and peoples.

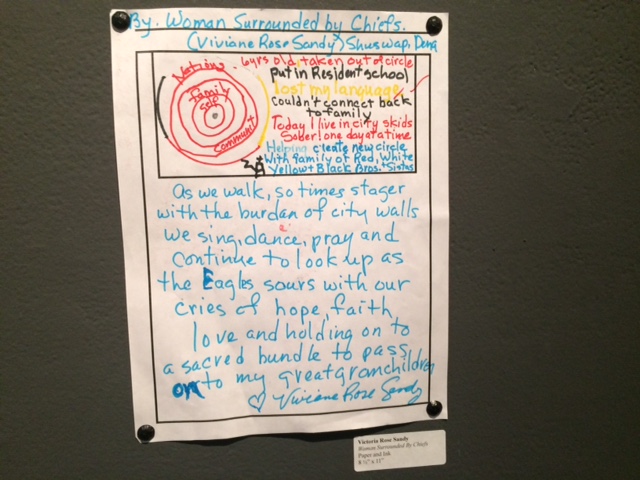

The walls and ceiling of the gallery are strewn with artwork from current and former residents of the Downtown Eastside, documenting their struggles from the standpoint of survivors. Hanging from the ceiling are fabric hangings featuring quotes from Nikkei elders and Downtown Eastside residents, and small cardboard circles with drawings and writings from community members.

Other pieces included a large colourful banner created by the DTES community, a series of photographs taking place in the DTES, a line of dioramas, strings of postcards visitors can also add to, and a series of bright abstracts by Michelle Tully. In spite of the subject matter being colonial and capitalist violence, these pieces—created from a series of facilitated arts workshops—each bring together a sense of community solidarity I rarely see in art galleries.

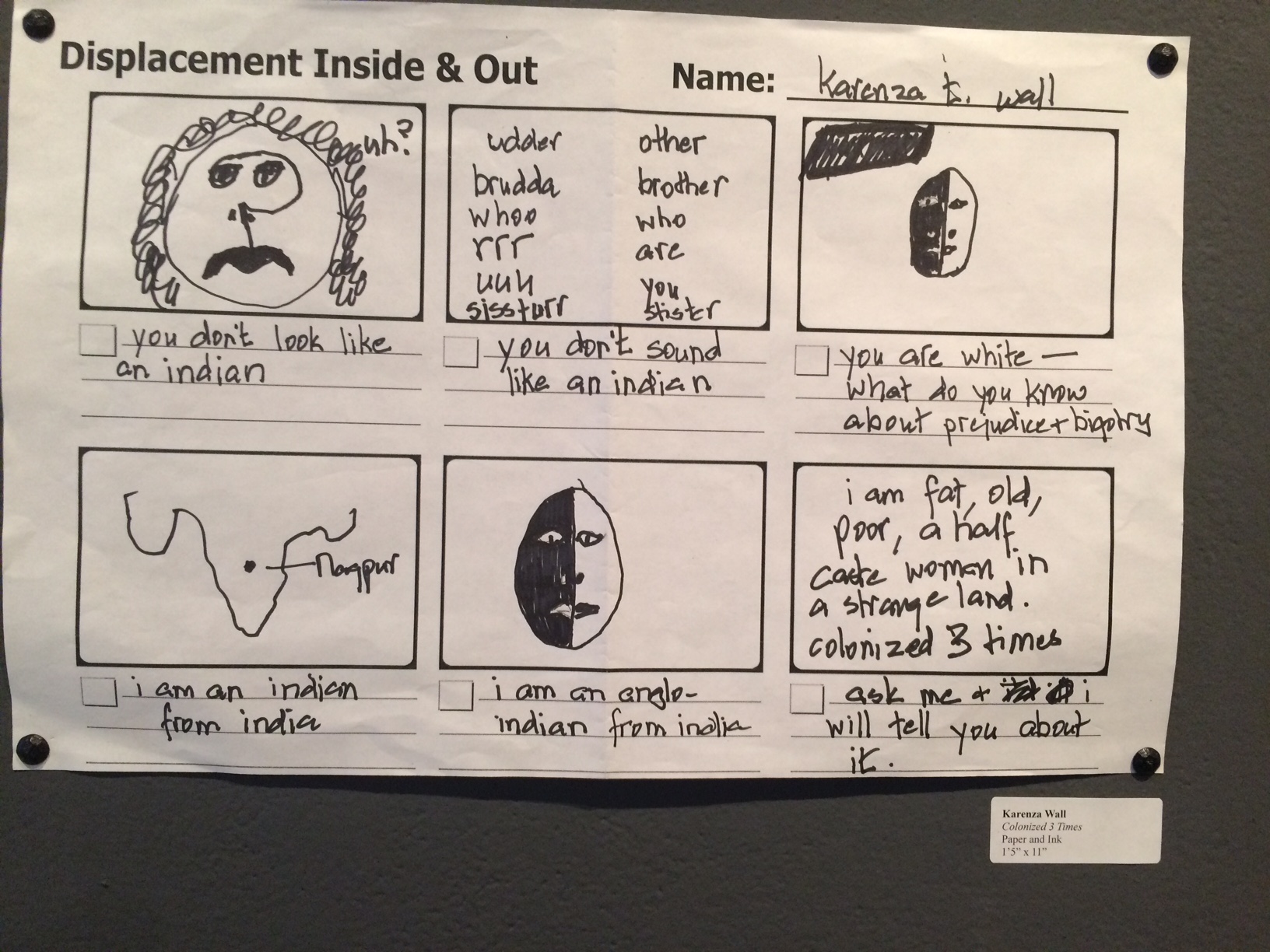

One of the most powerful sections of the exhibit is “Displacement Inside and Out,” a series of storyboards facilitated by Andy Mori during the project’s first Human Rights Art Workshop at Aboriginal Front Door. With the exception of a few single-panelled pieces, these storyboards involve six panels of images and written lines below, each drawn using felt markers on a photocopied worksheet.

These pieces suggest the beginning stages of a longer process of storytelling, each having the potential to become animated, filmed, or staged. In other words, the vivid stories of trauma told here are in process—testifying to an ongoing experience that can change drastically depending on what happens next.

Another way of reading these panels is to see them as submissions for an elementary school assignment, as comics exploring the art of storytelling. At the risk of infantilizing artists, this reading provokes a re-evaluation of what counts as teachable histories and narratives.

Instead of being hidden away and graded, these ‘assignments’ make each ‘student’ the knowledge-bearer, the creators of historical narratives that mainstream pedagogies fail to offer.

Works Cited

Masuda, Jeff. “The Right to Remain in Vancouver’s Nihonmachi/Downtown Eastside.” The Bulletin (2014): n. pag. Revitalizing Japantown. The Bulletin: a Journal of Japanese-Canadian Community,history + Culture, 8 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Sylwia. “The Right to Remain.” Gallery Gachet. Gallery Gachet, 25 Feb. 2015. Web. 16 Mar. 2015.