Tabrizi’s “Crossed”: Language and Diasporic Communities by Andrei Rizea

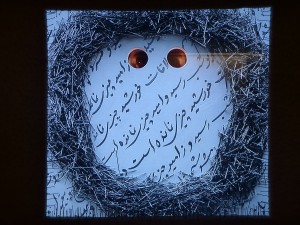

Tabrizi’s art exhibit located at the Grunt Gallery in Vancouver (350 E 2nd Ave – Unit 116 ) titled Crossed, depicts “thirty-eight framed framed photographs…arranged in a partial grid, [where] the warmly lit eyes of the artist are pictured behind cool white panels incised with circular layouts…[composed of] heaped dressmaking …[and] beneath the layer of pins, Farsi script tilts diagonally, while English words are rendered on top of the photograph, in dripping red cursive placed where the mouth should be” (Brown, 2014). The exhibit also features “an accompanying video, [where] Tabrizi’s voice speaks what at first seems to be a translation of the Persian poem that someone is singing in the background, in the classical style” (Brown, 2014). For the purpose of this review, I will focus on the phonetic aspect of the exhibition.

What striked me as a key theme to this exhibition upon coming across the Farsi characters in stark contrast with the visually striking blood red English words, and more significantly, the audio presentation, was the notion of language and its discursive properties, not only as means to communicate thoughts, but as a form of miscommunicate in terms of language and cultural barriers.

As I entered the studio, after becoming disoriented with the deceiving apartment-like façade of the gallery, I stumbled upon a room that was entirely white, split on two levels, and leading to a dimly lit corridor and space at the back of this exhibit. Consequently, the sheer vastness of the whiteness that seemed to engulf all of the space and render it infinite through the indistinguishable corners, evoked a sense of limitlessness, purity and a cold tone of formality. At this moment, the very discourse of architecture and space became a part of the languages inscribed upon the photographs.

In addition, the first thing that triggered my sensory perception was sound: the viewer is greeted with the sound of a doorbell, followed by an non-comprehensible looping ‘Middle Eastern’ male voice singing in the background (assuming you are not of Iranian descent), and out of perpetual surprise (as it seems you are alone at this point), you’re immediately draw back into a more familiar Anglicised world through the ‘re-assuring and comforting’ voice of a supervisor somewhere off in the distance, eventually revealing itself and easing one’s confusion and eerie vibes.

Although appearing to be simply an austere experience of visiting the exhibition, this ‘staged-like’ performance on the part of the gallery is exactly what I believe this exhibition is about: our inability to cross certain cultures, to become accepted within diverse normative groups, and the lost/discomforting feeling accompanying it by not being able to really see who or what is behind that foreign voice. The visitors become the ones marginalized this time.

After coming across the asymmetrical grid of repeated photographs, I was guided to a small open space at the back of the, where the singing was coming from as described earlier on. There, I saw the same photograph, but this time the eyes seemed to be moving. Tabrizi’s face was inaccessible to the public, where the dictation of a Farsi poem, interwoven with a voice-over of Tabrizi speaking English was presented in a rather powerful concoction of emotions: the viewer becomes unable to distinguish the difference between Farsi and English, where the two languages seem to flow out of one another, becoming one seamless entity. The separation between receiving dominant societies and incoming diasporic communities are erased. Tabrizi presents forth this unison of cultures in a strong, stern and impactful tone, alternating in between a tone of acceptance through a dissatisfied and frustrated tone.

In sum, the viewer enters Tabrizi’s world: we become a society that doesn’t fit, that is viewed as ‘different or as an outsider,’ and we even begin to feel this pain from the inside as we stare into the hardships of Tabrizi’s eyes. However, we become aware that at the core, the essence and centre of our psychological make-up, we are all the same. Language becomes universalised rather than exclusive.

Source: Brown, Lorna. In Your Face. 2014. PDF.