Visualizing a Culture for Strangers: Chinese Export Painting of the Nineteenth Century

This exhibit presents a selection of Chinese paintings from Chinese artists who use “Western spatial form and perspective methods” to paint Chinese sceneries. These Chinese artists were asked by the European commissioners to employ Western techniques in order to produce paintings that “[the Westerners*] could relate to and understand.” These Chinese export paintings gained considerable popularity in Europe because, the curator tells us, they were able to “satisfy a Western curiosity and appetite for stereotypical images of the cultural life of China,” and the curator adds that, in Europe, “there existed a fascination with every aspect of Chinese life, from birth to death.”

The Westerners’ extraordinary eagerness to learn about “every aspect” of Chinese culture from “birth to death” is interesting. It seems that we can attribute their eagerness to appreciate another culture to commendable values such as cosmopolitanism and a willingness for intercultural understanding. But is such an interpretation accurate—the interpretation of their motivation for consuming Chinese export paintings?

The Westerner’s interest in Chinese culture, as stated, is problematic if not self-contradictory. They appear to be eager to appreciate every aspect of Chinese culture but, at the same time, they readily rejected the Chinese aesthetic norm (by choosing the Westernized export paintings over the traditional Chinese paintings) which is an important aspect of Chinese culture.

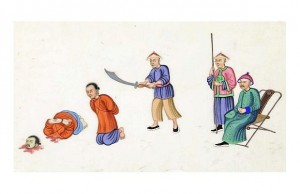

The curator’s statement that the Westerners were “fascinated with every aspect of Chinese life,” therefore, needs to be scrutinized. Certainly, the scope of their self-proclaimed interest in Chinese culture is not holistic but restricted to only certain aspects. In particular, the majority of the paintings at the exhibit highlight the themes of court punishment, public festivals, sightseeing and so forth—themes that appeal to entertainment values more than anything else. Those paintings therefore are superficial and narrow depictions of Chinese culture; certain more important aspects of Chinese culture, such as the aesthetic norm for painting, were ironically neglected if not rejected by Western audiences. Their preference of the Westernized export paintings over the tradition Chinese paintings, therefore, is telltale of the narrowness in their interest in Chinese culture; that is, they were “fascinated” by Chinese culture only to the extent that it was entertaining for them.

The Westerners’ “fascination” with Chinese culture could be more appropriately described as touristic curiosity than humility for intercultural understanding. In additional, their eagerness to consume the export paintings also seems to be associated with a sort of colonial satisfaction which was validated by the colonial culture predominant in Europe at the time. This colonial satisfaction is gained when the Westerners—no matter how superficially or misled—“familiarized” themselves with Chinese culture by looking at the Chinese export paintings, as the grasp of exotic Chinese culture may give them a sense of colonial “conquest” over it. Their motivation for learning about Chinese culture, therefore, was constituted by their colonial consciousness and their search for entertainment. In contrast, their motivation shows little sign of cosmopolitanism or a willingness for intercultural understanding.

The emergence of Chinese export art paradoxically reveals the lack of interest in intercultural understanding of nineteenth-century Western audiences. However, the intent here is not simply to criticize the nineteenth-century Westerners. The emergence of “export paintings” also reflects something that we all experience: the tension between the drive of curiosity and conformity to the norm, the desire for novelty and the desire to stay the same. One could, interestingly, be curious about an exotic culture and yet be completely non-serious about appreciating it deeply. How often are we willing to surrender our own cultural identity and immerse ourselves in a different culture?

————————–

*The phrase “Western audience” is of course over-generalizing. From the clues I could get from the curator’s blurb, the phrase seems to indicate the 19-century mid-class Europeans who had some travelling experience in China, people like “foreign dignitaries, businessmen, merchants, traders,sailors,and missionaries..”

![image[2]](https://blogs.ubc.ca/engl464k/files/2015/03/image21-300x225.jpeg)