“You will honour us to become witnesses”: c̓əsnaʔəm, the city before the city

I would like to acknowledge that this review is written from the perspective of first-generation settler who studies and lives on unceded Musqueam territories. I am ever grateful for this opportunity.

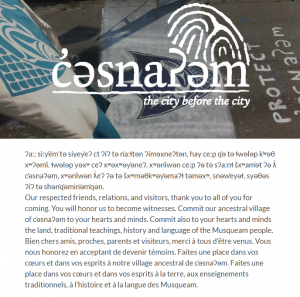

A trilingual invitation welcomes visitors to “c̓əsnaʔəm, the city before the city,” a three-part exhibition resulting from the partnership between UBC’s Museum of Anthropology (MOA), the Museum of Vancouver, and the Musqueam First Nation (fig. 1). The exhibition at MOA, in particular, focuses on “Musqueam identity and worldview. It highlights language, oral history, and the community’s recent actions to protect c̓əsnaʔəm” (MOA n. pag.). To do this, several interactive exhibits creatively connect Indigenous orality with digital technologies.

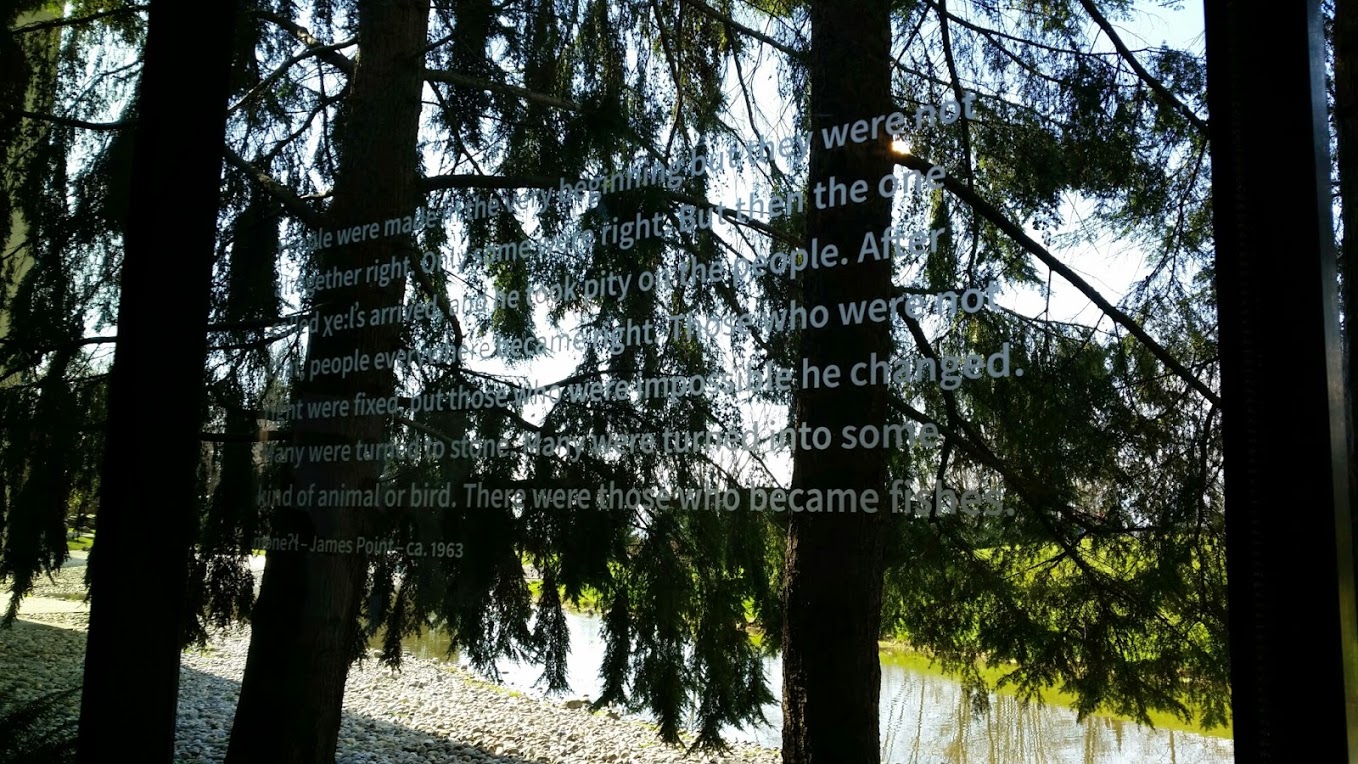

The gallery is arranged with screens that stream videos of water lapping at rocks, distant shorelines, or animated etchings of First Nations objects and peoples, which play automatically or after manual prompting. Each one is overlaid by a Musqueam speaker who narrates a story about place names or personal experiences, while English subtitles translate the account. On one of the posters that wrap around the walls of the gallery, bright blue letters firmly assert: “Our stories are our truths.”

I watched the camera pan across an urbanised Vancouver skyline, metal skyscrapers beckoning to trawling cargo ships, as məṅeʔɬ James Point mumbled in my ears: “[That maiden] faced the water and cried every day. When the xet’l arrived, she was the first person they spoke to. . . . She then became nothing. Only her name remained. Just like the Indian name for that place.” Through the combination of videos and storytelling, I saw seemingly different places emerge and overlap: the recognisable edge of modern-day Coal Harbour, the site of the maiden’s prophetic grief, and məṅeʔɬ’s resonant metaphor on the loss of personhood that is inadequately buttressed by the remainder of a name. Reclaiming place names—like c̓əsnaʔəm—recognises the loss of identity, not replaces it. Language, land, and identity are inexorably tied; to express that, technology is inventively applied to facilitate “Musqueam ways of educating” (MOA n. pag.), to great success.

Thus, what happens to identity when neither land nor language are available? How does displacement affect identity formation? The innovative “tangible table” explores these questions by attempting to bridge the past and the present. It juxtaposes contemporary icons and objects with Indigenous ones to unsettle our understanding of how colonial structures have manifested in the present day. Coke cans, house keys, quarters, and identity cards can be placed into a ring that reveals a passage on the object’s colonial connections once paired with the appropriate Indigenous token (fig. 2). Each item ties directly to government mandates on Indigenous identity, emblems of unequal trade markets, and/or lost cultural practices. The activity exposes the culture of capitalism as a form of violence, for the passages detail how innocuous symbols can obscure histories of oppression, persecution, and brutality.

“c̓əsnaʔəm, the city before the city” at the MOA is an engaging and humbling experience, one that inspires visitors to leave with more questions than when they entered.

Works Cited

MOA. “c̓əsnaʔəm, the city before the city.” MOA Exhibitions. Vancouver: MOA, Jan. 2015. Print.