“In order to address this question you will need to refer to Sparke’s article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” You can easily find this article online. Read the section titled: “Contrapuntal Cartographies” (468 – 470). Write a blog that explains Sparke’s analysis of what Judge McEachern might have meant by this statement: “We’ll call this the map that roared.””

Cartography is succinctly defined as the science and art of map-making. This vague description, however, does not fully communicate the power that exists behind a map.

A common theme in Geography is everything exists somewhere. Everything in the world has a location and a value, which we rely on to understand the environment around us. Except, this reliance can lead to a power imbalance for the makers and holders of the maps, being that maps are an abstraction of reality.

Not only can maps be inherently deceitful, but they are also inherently a colonial tool. On first arrival in Canada, European explorers and settlers brought with them centuries old knowledge of cartography that began with the Ancient Greeks. To the Indigenous populations the colonists then encountered, this would have been a new and very different perspective on the Indigenous pre-colonized worldview. Even today, maps convey the fundamental colonial notion of a “singular national origin” and “heterogeneous past” (Sparke 468), omitting the other origin stories present within Canada.

That is why, when two First Nations (the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan) came forward with their own cartographic evidence of their sovereignty in 1987, the judge presiding over the trial, Chief Justice Allan McEachern, described one of their maps as “the map that roared” (Sparke 468). Matthew Sparke (1998) suggests in his article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation”, that a possible interpretation of McEachern’s statement is a reference to the colloquialism, “paper tiger” (468).

A “paper tiger” is something which externally appears to be powerful or dangerous, but in actuality is internally weak or ineffectual (Merriam-Webster). Initially, the judge found these maps to be threatening. In an attempt to frame their sovereignty in a way that the court may understand, the First Nations utilized cartographic tools, which naturally carry a colonial understanding of the world. However, to the Chief Justice, their integration of traditional knowledge into a tool that historically only ever carried the knowledge of the colonial origin story, implied to him that the First Nations were attempting to undermine the world view that he understood. Additionally, he could not fathom the power and knowledge that the map was trying to convey, as he lacked an understanding of the duality of Canada’s origin stories. Therefore, he dismissed the map, finding its traditional knowledge of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan to be ineffectual in placing their “ownership and jurisdiction within” the Canadian context (Sparke 463).

Sparke also connects McEachern’s statement to a political satire called “The Mouse that Roared”, in which a small European country, whose pre-industrial economy relies on wine exportation, wages war against the United States after a California winery causes the small country’s economy to collapse (Wikipedia). This reference, on one hand, characterizes the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan as archaic through the comparison to the pre-industrial, and therefore backwards, European nation. On the other hand, however, this reference also implies the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan’s resistance and “roaring refusal of the…accoutrements of Canadian colonialism on native land” by equating the First Nations’ fight for sovereignty to the European country waging war against the U.S. (Sparke 468). This implies almost a sense of foolishness on the part of the Indigenous peoples for even trying to fight against the colonial worldview and further added to the Chief Justice’s disregard of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan’s battle for “agency and territorial survival” (Sparke 470). Therefore, Chief Justice Allan McEachern dismissed the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan’s case on the basis of questioning the colonial worldview.

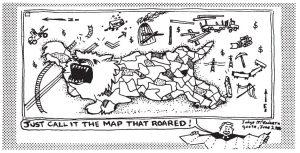

“A Map that Roared.” Reprinted from Monet and Skanu’u (1992), by kind permission of Don Monet. From Matthew Sparke’s “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation”.

References:

Gartner, Georg. “The Relevance of Cartography.” ArcNews. Esri, 2013, https://www.esri.com/esri-news/arcnews/winter1314articles/the-relevance-of-cartography. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

“Paper Tiger.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/paper%20tiger. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

Sen Nag, Oishimaya. “What is Cartography?” Worldatlas. n.p., 17 Aug. 2017, https://www.worldatlas.com/what-is-cartography.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

Sparke, Matthew. “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada,

Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88:3 (1998): 463-495. Taylor and Francis Online, https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00109. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

“The Mouse that Roared.” Wikipedia.com. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mouse_That_Roared#Film_adaptation. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

Hi Casssie,

I really enjoyed your detailed and thoughtful analysis of Matthew Sparke’s article. You expressed the connection between cartography and colonialism in a way that I noticed but found challenging to articulate. In particular, I found your description of maps as an “abstraction of reality” that can be manipulated to propagandize certain ideologies helpful in conceptualizing how maps have been used to assert dominance and power throughout history. I was wondering if, given the way you’ve drawn connections between maps, power, and “paper tigers”, you could expand on the idea of the “map that roared” as a tool for resistance. What is the significance of this particular form? Did the Judge’s dismissal represent a disregard for the indigenous argument, or is his dismissal also in some ways an attempt to delegitimize an otherwise powerful and legitimate form of resistance?

Secondly, I noticed you said maps are “inherently colonial”; this really interested me, because although I also recognized the ways in which maps had been used throughout colonial history to craft imperialist and ethnocentric propaganda, I hadn’t considered whether or not the form itself is inherently colonial. I would certainly say all maps are biased as they are, by necessity, representative, but I had never considered whether they are inextricable from their colonial history. Could you expand on this?

Hi Charlotte,

In response to your first question, my answers are yes and yes. By dismissing the map, the judge was dismissing the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan’s case and knowledge as well as devaluing their resistance against a sole creation story, which their map was undermining.

As for your second point, as you point out, “maps had been used throughout colonial history to craft imperialist and ethnocentric propaganda”. If this is so, then how would you ever remove this context from maps? Maps are another form of media (particularly older cartography traditions) and can you ever really remove any media from its context without losing its meaning? I think if you remove a map from what it was made and used for, you lose the map’s story and therefore it becomes unreliable. In geography, we are required to take GIS classes (essentially digitally mapping spatial data to solve a problem) and one of the most important things you learn is the value of metadata in any data set you obtain or map you make. The metadata tells you how reliable the data in the map is, and therefore how reliable the map itself is. If you remove this metadata – the story – then it’s really difficult to trust that what the map is saying to you is the truth. So, I think it is impossible to remove the colonial context from maps and cartography, because by doing so, you’ll be losing the map’s story and reliability.

Hi Cassie,

I answered the same question as you and in reference to “The Mouse that Roared” I learned that a lot of the context had to do with the Marshall Plan which was an economic aid program by the US towards Europe to help fix damage caused from WWII. In this case, I think Sparke’s could be noting Judge McEachern’s dismissal of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan map since he believed they were looking for compensation or aid since their land had been colonized.

What do you think about this? Do you see any connection to the Marshall Plan?

Cheers,

Kynan

Hi Kynan,

Thanks for your insight into the Marshall Plan. Your interpretation of the connection between “A Mouse that Roared” and the judge’s statement could be one of many possible interpretations of the reference. It makes me wonder if Sparke was trying to be ironic by including the reference in his analysis, since the US was willing to give aid to any war-torn country who requested it, while the judge did almost the exact opposite.

Hi Cassie,

I was really intrigued to read your response to this question – I have answered the same question in my blog but am impressed at the point of view that you have taken – the reference to colonialism as the “paper tiger”. I agree with you that maps are, ultimately, a colonial tool and that cartography, as you so well explain it, in this case worked in favour of colonial politics.

How much, in your opinion, colonial cartographers managed to erase “local differences” by imposing the map that covers the indigenous territory in such a different way?

Cheers and thanks,

Dana

Hi Dana,

Thanks for your question! I think colonial cartographers almost completely managed to erase the features in Canada that already existed, but which the colonial settlers chose not to see. Canada was viewed as a blank slate of sorts, and when mapped as such, completely failed to recognize the already existing indigenous territorial system that had been in place. Over the years, these maps have been reiterated over and over again, passed down to our children as they learn in school. This has now created a situation where indigenous peoples fighting for their land have to prove that their land is in fact theirs, all because colonial cartographers failed to map their indigenous boundaries.

Hi Cassie,

Thank you for your post! Colonialism and mapping have always been seen to be related, in the sense that cartography was a huge part of Colonial times. It’s interesting as to how skewed something that is seemingly as sound as mapping can be, given the bias that goes into making them. If we were to compare Indigenous maps with Colonial maps today, do you think there would be any stark differences besides the markings of boundaries?

Hi Katrina,

Thank you for your question! I think that the first thing that has to be considered is whether Indigenous people actually partake in cartography. In the court case which Sparke analyzed, the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan made maps to support their case because they thought that the judge would better understand their perspective if it was in format which he was familiar with. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that Indigenous peoples partake in mapping their knowledge regularly. And as we have learned in this class, many Indigenous cultures are oral. So I can’t say for certain whether Indigenous peoples have ever mapped their traditional knowledge to the same degree to which Western societies have or if it has always been solely passed down through oral tradition.

It does seem though, that Indigenous knowledge is being mapped by non-Indigenous people (with the support of Indigenous groups). In particular, I found this article very interesting and relevant to the topic: https://ipolitics.ca/2018/10/22/new-indigenous-map-makes-parliamentary-debut/

Hi Cassie,

I really enjoyed reading your blog post. I was especially interested by the comment that you mentioned about “The Mouse That Roared” in which a small European country’s pre-industrial economy relies on wine exportation.

Can you think of any other comparable examples between McEachern’s eurocentrism and events in today’s society?

Hi Alexandra,

Thanks for your question! There are honestly so many examples of similar instances to McEachern’s dismissal of the Indigenous maps in terms of a Eurocentric world view dominating in the minds of many Canadians. For example, I think Islamophobia could be considered an example. People are viewing a religion that they do not understand from the outside, and with some events that have occurred from 2001 till present, some people wrongly view Islamic people as a group who will harm the “Canadian way of life”. Really, it all seems to come down to a lack of understanding of other world views and a lack of ability or want to shift the Eurocentric world view to accommodate an Indigenous (or Muslim) world view.