We began this unit by discussing assumptions and differences that we carry into our class. In “First Contact as Spiritual Performance,” Lutz makes an assumption about his readers (Lutz, “First Contact” 32). He asks us to begin with the assumption that comprehending the performances of the Indigenous participants is “one of the most obvious difficulties.” He explains that this is so because “one must of necessity enter a world that is distant in time and alien in culture, attempting to perceive indigenous performance through their eyes as well as those of the Europeans.” Here, Lutz is assuming either that his readers belong to the European tradition, or he is assuming that it is more difficult for a European to understand Indigenous performances – than the other way around. What do you make of this reading? Am I being fair when I point to this assumption? If so, is Lutz being fair when he makes this assumption?

In “First Contact as Spiritual Performance,” Lutz explains that “one must of necessity enter a world that is distant in time and alien in culture, attempting to perceive indigenous performance through their eyes as well as those of the Europeans” (32). Although it may seem at first that Lutz is reinforcing differences between indigenous and European perspectives, this is in fact a false dichotomy which Lutz is quite cognizant of and latter collapses. Lutz argues that the first and ongoing contacts between indigenous peoples and Europeans as spiritual as well as material encounters.

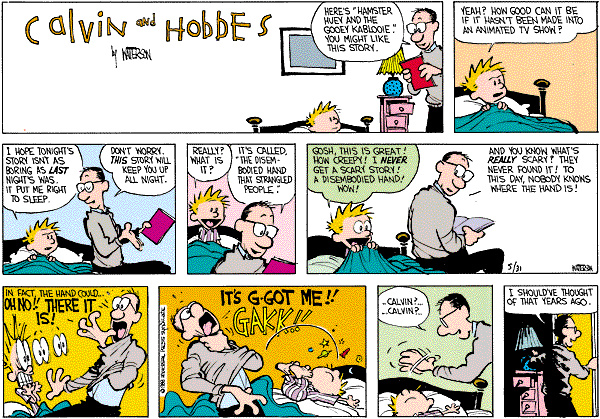

Lutz cautions against the downplaying of indigenous belief systems by pointing out how “the attribution of rationality to other peoples [is] a projection of European ideas to the rest of the world.” Many indigenous accounts of first encounters reveal how Native peoples linked the arrival of Europeans and their ships with the supernatural world. The Gitxaala, for example, protect themselves from supernatural beings by rubbing themselves with urine, which is why the native fisherman in the story doused himself in pee when a strange vessel landed on a beach sacred to the transformer Raven (featured image: the only Raven Transformer I knew of before “First Contact”).

But Lutz argues that Western explorers, merchants, and missionaries were equally influenced by spiritual motivations. He writes, “a closer look at the Europeans shows that their rational behavior [too] was determined… by their non-rational spiritual beliefs” (32). A prime incentive for Spanish exploration was evangelism, and Enlightenment Christianity saw science as a way to appreciate God’s creation while seeking to justify the superiority of European Christians to pagans.

At the end of the day, these narratives of first contact reveal how both indigenous peoples and Europeans demonstrate Anthony Pagden’s principle of attachment. Instead of immediately destabilizing traditional beliefs, they interpreted their encounters as ongoing proof of these beliefs, processing the new through the familiar.

Remarkably, Lutz himself forms assumptions about his audience. In asserting that “one must of necessity enter a world that is distant in time and alien in culture [and] perceive indigenous performance through their eyes as well as those of the Europeans,” Lutz assumes his readers belong to the European tradition. This is ironic because this text not only seeks to dismantle the binary between “mythic and historical modes of consciousness” in first contact stories but also in the reader. Lutz calls for the audience to “step outside and see one’s own culture as alien and to discern the mythic in the performances of one’s own histories” (Lutz 32), while himself falling trap to the assumption that it is more difficult for Europeans to understand Indigenous performances, thereby reinforcing the Eurocentricity that he criticizes other cultural scholars of.

At the same time, Lutz’s assumption may be grounded in historical fact. Over the past century, around 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend residential schools.

Residential schools were established with the assumption that aboriginal culture was unable to adapt to a rapidly modernizing society. It was believed that native children could be successful if they assimilated into mainstream Canadian society by adopting Christianity and speaking English or French. Students were discouraged from speaking their first language or practicing native traditions. (“A History of Residential Schools”)

Perhaps this period of cultural genocide and forced assimilation has in some way made indigenous people more comprehending of (if not sympathetic to) Western ideologies than vice versa. One question I have for Lutz–and you–is where people who come from neither Western nor indigenous culture stand. Are we lumped in with the Europeans? Or, more generally speaking, do you think it is more difficult for Westerners to understand Indigenous performances?

———————————————————————————————————-

Works Cited:

“99 Golden Facts About Urine.” Random Facts. 2012. Web. 19 Feb. 2016

“A History of Residential Schools in Canada.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 07 Jan. 2014. Web. 12 Feb. 2016.

Lutz, John. “First Contact as a Spiritual Performance: Aboriginal — Non-Aboriginal Encounters on the North American West Coast.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indigenous-European Contact. Ed. Lutz. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. 30-45. Print.

Pagden, Anthony. European Encounters with the New World. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1993.