Explain why the notion that cultures can be distinguished as either “oral culture” or “written culture” (19) is a mistaken understanding as to how culture works, according to Chamberlin and your reading of Courtney MacNeil’s article “Orality.”

In his influential work, Wealth of Nations, published 1776, Adam Smith introduced the idea of stadial history, which assumes that all civilizations will develop in the same manner: from pre-agricultural (aka “savage”), to early-agricultural (aka “barbaric”), to industrialized (aka “civilized”). According to this line of thought, an explorer such as George Vancouver who “discovered” the Maori in New Zealand would really be meeting a version of his great-great-great-great-great… grandfather. (Remarkably, this mode of thinking—also called, unilinearism—has influenced non-European writers themselves—most notably black abolitionist Equiano, who argued in The Interesting Narrative (1789) that emancipated Africans would be a greater benefit to the British economy, since the entire continent of Africa would inevitably “adopt the British fashion, manner, and customs.”

Stadial, or conjectural, theory has been a key culprit in reinforcing the false dichotomy between oral and written culture. In her article “Orality”, Courtney MacNeil details how oral cultures have traditionally been associated with tribal groups while written cultures are ‘proof’ of more ‘advanced’ civilizations. Both MacNeil and J. Edward Chamberlin cite the Toronto School of Communication as a major advocate of the primacy of the written word and the “primate-cy” of the spoken word.

In his book If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories?, however, J. Edward Chamberlin, takes a different stance. He collapses the binary between oral and written traditions:

All so-called oral cultures are rich in forms of writing, albeit non-syllabic and non-alphabetic ones… On the other hand, the central institutions of our supposedly ‘written’ cultures… are in fact arenas of strictly defined and highly formalized oral traditions… (Chamberlin 19)

Chamberlin argues that every culture’s are invested in both oral and written elements, which are inextricably “entangled with each other” in our stories and songs. I can attest to the fact that this certainly holds true in Chinese culture. In our 5000 years of recorded history, we have accumulated a rich literary (poems, ancient texts, calligraphy) and oral (folk songs, operas, chants) repertoire. Oftentimes, these interface and overlap. For example, operas are written down so that they can be performed; books of poems, vice versa, are committed to memory in school.

Today, digital “literature” also upends common assumptions about and blurs the lines between these two types of media. For example, audio-recording sites like Youtube preserve orality by allowing them to be replayed while instant messaging and social media prove that text-based communication no longer holds permanence. Even the existence of this online classroom—ENGL 470A—is proof that “technological advances in communication have been part of the impetus to rethink the divisive and hierarchical categorizing of literature and orality” (Paterson). Our “lectures” are have once again come back to the original sense of the word—to read—what Professor Paterson had to “say” about Lesson 1.3. (Her introductory vlog, on the other hand, is oral.)

Instead of distinguishing culture as either oral or written, we might think dialectically of culture as both. Courtney MacNeil is careful to make a distinction between and oral and orality, however. Borrowing from Meschonnic, she writes, “orality is not the opposition of writing, but rather a catalyst of communication more generally, which is part of both writing and speech” (Orality). Orality is a means of communication, a means of accessing collective memory or innate human truth, and oraliture, coined by Edouard Glissant, a repository of both written and verbal arts.

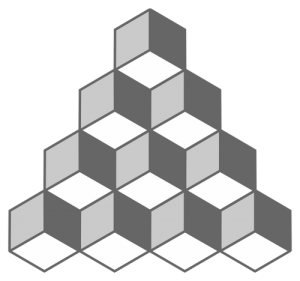

One last point: the principle of superposition within quantum theory posits that something can exist in multiple states at the same time. (For example, are these cubes facing in or out? Both.) The truth about stories is that they can be both oral and written. Like this optical illusion, however, sometimes it’s difficult to recognize its dialectical nature. In the rest of his book, Chamberlin goes on to deconstruct other dichotomies—home and homeless, reality and imagination—and helps us see that these contradictions can coexist symbiotically. It is only when we can come to terms with these states of superposition that we will be able to participate in these “ceremonies of belief” and enter into one another’s stories.

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Reimagining Home and Sacred Space. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2004. Print.

Necker Cube Illusion. Digital image. Web. 23 Jan. 2016. <publicdomainvectors.org>

MacNeil Courtney. “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. Uchicagoedublogs. 2007. Web. 19 Feb. 2013.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 1.3.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies: Canadian Literary Genres. University of British Columbia, 2013. Web. 6 Jan. 2014.

Hello Beatrice, thanks for the wonderful post. I do agree with Chamberlin that distinguishing culture as either “oral culture” or “written culture” is mistaken. Even though oral elements are dominant in societies that are not civilized, written elements are also present in such societies. In fact, oral and written cultures are intertwined. The example you give is testimony to this: “I can attest to the fact that this certainly holds true in Chinese culture. In our 5000 years of recorded history, we have accumulated a rich literary (poems, ancient texts, calligraphy) and oral (folk songs, operas, chants) repertoire. Oftentimes, these interface and overlap. For example, operas are written down so that they can be performed; books of poems, vice versa, are committed to memory in school.”

Some facts about African countries show clearly that Adam Smith’s idea of stadial history, “which assumes that all civilizations will develop in the same manner: from pre-agricultural, to early-agricultural, to industrialized” is untrue. According to Back History Studies,

21. In around 300 BC, the Sudanese invented a writing script that had twenty-three letters of which four were vowels and there was also a word divider. Hundreds of ancient texts have survived that were in this script. Some are on display in the British Museum.

47. Many old West African families have private library collections that go back hundreds of years. The Mauritanian cities of Chinguetti and Oudane have a total of 3,450 handwritten mediaeval books. There may be another 6,000 books still surviving in the other city of Walata. Some date back to the 8th century AD. There are 11,000 books in private collections in Niger. Finally, in Timbuktu, Mali, there are about 700,000 surviving books.

48. A collection of one thousand six hundred books was considered a small library for a West African scholar of the 16th century. Professor Ahmed Baba of Timbuktu is recorded as saying that he had the smallest library of any of his friends – he had only 1600 volumes.

49. Concerning these old manuscripts, Michael Palin, in his TV series Sahara, said the imam of Timbuktu “has a collection of scientific texts that clearly show the planets circling the sun. They date back hundreds of years . . . Its convincing evidence that the scholars of Timbuktu knew a lot more than their counterparts in Europe. In the fifteenth century in Timbuktu the mathematicians knew about the rotation of the planets, knew about the details of the eclipse, they knew things which we had to wait for 150 almost 200 years to know in Europe when Galileo and Copernicus came up with these same calculations and were given a very hard time for it.”

According to the above facts, writing existed in Africa long before Europe. However, African culture is mostly oral in nature. That cannot be said to be a result of writing ignorance or slow rate of civilization. In my opinion, the African societal order and system made oral systems more relevant. In most African communities, the most important role of parents and grandparents was to pass down their traditions and cultures to their children and grandchildren. The system was so effective that it rendered writing, as a means of storing information, almost useless.

work Cited

“100 Things That You Did Not Know about Africa: African History Facts, Black History Facts, Little Known Facts.” 100 Things That You Did Not Know about Africa: African History Facts, Black History Facts, Little Known Facts. Web. 25 Jan. 2016.

Hi Minkyo!

Thanks for your very informative comment. Alas, I must profess to knowing even less about Black history than Native history, so the link was greatly appreciated! I think your bringing in of African culture to the discussion really enriched our dialogue. I especially appreciated your words, “According to the above facts, writing existed in Africa long before Europe. However, African culture is mostly oral in nature. That cannot be said to be a result of writing ignorance or slow rate of civilization. In my opinion, the African societal order and system made oral systems more relevant.” My only concern would be that we need to be careful about what we mean by “Africa” in order to avoid statements like “African societal order” that might come across as homogenizing. It’s important to recognize that there are many different tribes and cultures within the continent–each with their own oral and writing traditions. Perhaps a writing, and not an oral, system is the dominant in Timbuku.

Thanks again,

Bea

Hi Bea!

I was very tempted to write about this topic, but I’m glad that I have your post to read instead.

In particular, I was really intrigued by your discussion about digital literature. You were careful to say that this mode does not seem to overwhelm the literary space and instead, “blurs the lines.” This point resonates with and recalls Courtney MacNeil’s article, where she writes: “the computer does not initiate the dominance of one media form over another, but rather encourages their fusion within the pluralistic realm of the ‘global village.'”

The computer or the digital realm is not a domineering force, but rather becomes a different vehicle for stories to thrive in. Furthermore, it facilitates the creation of new modes of story telling, ones that do not solely depend on the medium of text.

I have a question. What do you believe are the limits to this “digital medium?” Audiobooks and videos of storytellers may exist, but is there something that is lost in the process of transitioning to the virtual realm? I have some thoughts of this of my own, but I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the matter.

Thanks for the lovely post!

Brendan

Hi Brendan,

Thank you for the thought-provoking question–I see you have your teaching hat on, and it fits! I think for every change in medium there will be give and take in terms of what is communicated about a story. Walter Benjamin was struggling with a similar question 80 years ago when he wrote about the loss of “aura” in his groundbreaking essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In this essay, he talks about how technological reproduction makes art accessible to masses but also loses something magical or original in the process. I highly encourage you to check it out if you haven’t yet come across this essay! (www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm)

In regards to storytelling in the digital realm (you’ll notice that I’ve narrowed down your question), what first comes to mind is that the physical immediacy or stage presence of the storyteller is lost during the transition to virtuality; even in a video, the orator is shrunk down to the size of a Borrower on your laptop screen. There’s also a certain rigidity to recordings too that snuffs out the magic of storytelling as a performative act–a listener cannot interrupt, and the storyteller cannot shape his/her tale to fit the audience.

Now that you’ve opened this can of… tuna, I’m interested to hear your reflections.

Thanks,

Bea

I forgot to respond to this!

What you’ve just written perfectly reflects my own thoughts on the matter too. I love the analogy to The Borrowers, by the way. One other element I think is lost is the ability for the performer to adapt to his or her audience. Without knowing who is on the other side of the screen, and considering how broad this potential demographic may be, the performer may have to tailor their oral tradition to become a more general story. Orators from long ago included references to other stories to bring about certain moods, thoughts and morals to their main narrative and the audience would understand these allusions.

Thanks for the insightful reply. Always appreciate it!