Write a blog that explains Sparke’s analysis of what Judge McEachern might have meant by this statement: “We’ll call this the map that roared.”

As a child, I dreaded September—not for a lack of love for learning—but because I would have no swashbuckling vacation tale to flaunt on the school playground. While my peers came back with camp songs, road trip souvenirs, and great tans, my routine summer “pastime”, if it could so be called, was studying for RCM music exams. Needless to say, no one else was moved to tears by the too-young death of Franz Schubert or the fugal genius of J.S Bach’s Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. My story was soon lost in the cacophony of excited classroom chatter.

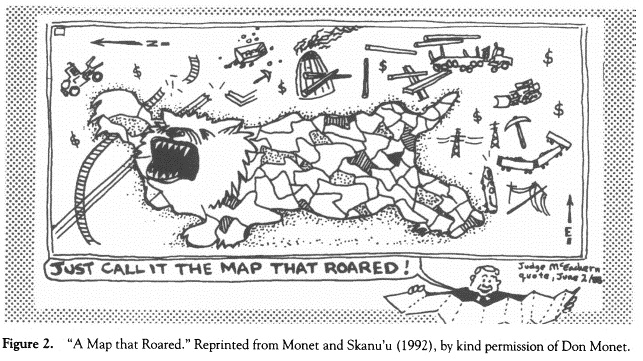

In his article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation,” Sparke also pays attention to another voice drowned in the clamour of opposing historical perspectives. Overlaying musical and geographical metaphors, the author imagines Canada’s heterogenous past as a polyphonic composition. No story other than that of the Gitxsan people’s attempt to outline their sovereignty in a way the Canadian court might understand better captures Spark’s reimagining of Canadian history as “contrapuntal cartography.” He writes, “the contrapuntal dualities of Delgamuukw v. the Queen made the location of national discourse a contentious question through a repeated return to maps” (468). While unfolding a map of traditional Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en territory, Chief Justice Allan McEachern was alleged to have declared, “We’ll call this the map that roared.”

There are many layers to Judge McEachern’s seemingly innocuous quip. Taken at face value, he may have been gesturing to the colloquial term “paper tiger,” a popular contemporary reference to large sheaths of paper. The First Nations map under scrutiny was indeed a large one. Sparke also considers a more weighted reference to the film “The Mouse that Roared” (1959), a Peter Sellers film that satirized Cold War politics. Read in this light, this statement may imply that that the Gitxsan were a pathetic, backward nation.

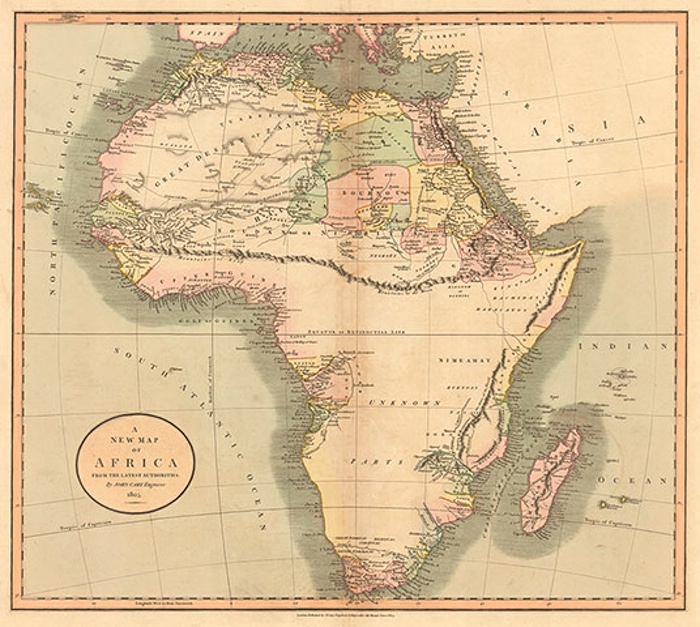

Finally, the Gitxsan people’s contrapuntal cartograph or roaring map evokes the idea of loud resistance or dissent. During the 1800’s, mapmakers often left maps unprinted where the topography is unknown to European. Globe owners often subscribed to updates provided by their local print shop as European cartographers filled in more details of parts of the world previously uncharted by Europeans. The updates were pasted over the existing surface of the model globes. This concrete representation of terra nullius no doubt reinforced the popular conception of spaces unvisited by Europeans as “blank spaces.”

Given this history, the Gitxsan were cognizant of that politics was at work even in geographical boundaries. Remapping the land demonstrated a “refusal of the orientation systems, the trap lines, the property lines, the electricity lines, the pipelines, the logging roads, the clear-cuts, and all the other accoutrements of Canadian colonialism on native land” (Sparke 468). It was an effort, first, to “white out” the arbitrary lines in the sand that White people had laid down as law. Having chased “white out,” however, the Gitxsan were wiser than to let the map stay blank. Subscribing to place names outside of the Western geographical canon was the Gitxsan’s assertion of a countersubject that sought to drown out the voice of the dominant discourse.

Each community has an intimate connection with place, which affects the relationships between community members, their sense of responsibility for their environment, and collective memory. As Wallace Stegner puts it, “no place is a place until the things that have happened in it are remembered in history, ballads, yarns, legends, or monuments.” For the Gitxsan, these maps were transliterations of their adaawk, stories that inscribed the land with the history of the Gitxsan peoples. “Reading maps that chart territory,” writes Dr. Erika Patterson in Lesson 2.3, “we are in a contact zone that stretches across the disjunction of time and history.” I would argue that these maps served as bridge that connected the Gitxsan nation to both their past and future. Not only were the Gitxsan reaching into the past to affirm their right of place in the present, but they were thinking proleptically, imagining a future for themselves based on the past—a future when they would no longer be governed by white laws, names, or maps. So, while unlike the Rastafarians, the Gitxsan do not make up their stories—their adaawks are true—by creating these maps, they too participate in storytelling that will “bring them back home while they wait for reality to catch up to their imaginations” (Chamberlain 77).

McEarchern’s offhand remark is a simultaneous dismissal and recognition of the Gitsxans’ claim. By recognizing, albeit disparagingly, that he heard a noise, McEarchern allowed that the Gitsan people did have voice and agency—and a strong and roaring one indeed. In doing so, McEarchern unsuspectingly affirms and welcomes the Gitsan’s songs and stories into the complex contrapuntal fabric that makes up Canada’s history—a history that neither begins nor ends with European Native first contact, a history whose voices are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and contour, and finally a history which is beautiful and alluring precisely due to its perpetual cycles of dissonance and resolution.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, Edward. If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. AA. Knopf. Toronto. 2003. Print.

Glenn Gould. The Well-Tempered Clavier. Youtube. Web. 02 Mar. 2016.

“Our Land” Gitxsan First Nations. Web. 02 Mar. 2016.

Patterson, Erika. “Lesson 2.3.” ENGL 470A: Canadian Studies. Web. 02 Mar. 2016.

Rogers, Simon. “Africa Mapped: How Europe Drew a Continent.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 2012. Web. 02 Mar. 2016.

Sparke, Mathew. “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88.3 (1998): 463- 495. Web. 04 April 2013.

Stegner, Wallace. “The Sense of Place.” Random House,1995. Web. 02 Mar. 2016.