Assignment 3.3: Write a blog that hyper-links your research on the characters in GGRW according to the pages assigned to you.

Assigned pages 156-171 1993 version (pages 187-206 in 2007 edition)

Note: I will be referencing page numbers for the 2007 edition of the novel

The complexity of King’s interwoven plot continues to surprise me as I work through this novel. There are so many different elements at work in just the 15 pages I am analyzing and hyper-linking. First I am going to break down the allusions of the major character that appear in these pages, and then I will discuss some of the underlying themes the characters are connected with.

Main Characters:

Buffalo Bill Bursum

This character is an allusion to two historical figures: Holm O. Bursum and Buffalo Bill (Flick 148). Holm O. Bursum was a Senator from New Mexico and is most known for his controversial land bill that would have taken Pueblo land away from these people while concealing that this was the bill’s purpose. The second figure this character alludes to is the famous Buffalo Bill (William F. Cody). Cody exploited ‘Indians’ for entertainment in the 1860s and 70s with his touring Wild West shows (Biography.com Editors).

Changing Woman:

The Changing woman is a character taken from Navajo mythology. She is a deity and often represents the power of the earth and the ability women have to create and sustain life (Flick 152). She also ages with the seasons in a cycle that never ends(grows old and then young again). One interesting aspect is that in the passage I was assigned Changing woman and Moby-Jane are alluded to as lesbians.

Ahab, Ishmael, and Queequeg:

These three characters are references to fictional characters in the novel Moby-Dick. Ahab is the captain obsessed with catching the white whale Moby-Dick While Ishmael and Queequeg are part of his crew. Ishmael has a close friendship with Queequeg who is a stereotypical representation of an indigenous person in Moby-Dick – cannibalistic tendencies and all (Flick 142). An interesting was to see Ishmael throughout the book is a character who has assumed an identity to overcome societal prejudices (Maithreyi 5). He hides his identity in some way by saying ‘call me Ishmael’ rather than ‘my name is Ishmael. An article by Maithreyi suggests King uses Ishmael’s hidden identity to show the dualities are linked to the dualities in North American land (5).

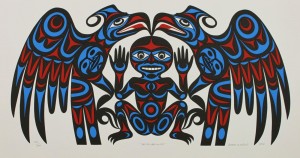

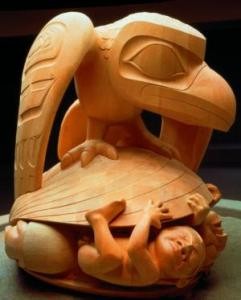

Coyote:

I don’t need to spend long on Coyote because we have looked at his symbolism throughout this course. He is a prominent figure in Native storytelling traditions and religion. He is a trickster figure who seems to have no restrictions placed on him as he jumps time periods or changes shape often. He even will directly influence the other characters.

Eli Stands Alone:

Eli is likely a reference to Elijah Harper who was a Canadian Oji-Cree politician who is most famous for opposing the Meech Lake Accord in 1990 (Marshall). Harper grew up in a residential school, went on to university then began a career in politics. Upon his death “hundreds lined up to pay their respects to the man who said ‘No'” (Marshall). Eli Stands alone said says ‘no’ to a project to build a dam that would flood native land. This fictional dam project alludes to a very real one called the Great Whale Project in Quebec that the Cree spent fighting for many years.

The De Soto:

The rental car Eli Stands Alone drives to the Sun Dance Festival is named after the famous explorer Hernando de Soto. Hernando is famous for his role in the conquest of Peru and he went on to explore the southeastern U.S destroying countless Native tribes along the way.

Underlying Theme:

There are many connections, allusions, and underlying themes throughout these pages in GGRW, but the one I want to focus on is how King shows that the Settlers history dominates Native history every time. Starting on page 187 (2007 edition) Bill Bursum complains how all “Indians [are] the same way”: against progress and overly sensitive. Eli Stands Alone held up the dam on “some legal technicality” and now Bursum’s lakefront property has gone to waste. These two pages are filled with so much meaning. Bursum criticizes Charlie and Lionel for adapting to Western society saying “they weren’t really Indians anymore” (187). This shows how many First Nations people are criticized by Westerners for adapting to society. Their First Nations heritage in societies mind stops counting. They can either be white or Indian – not both. Native people also criticize their people who integrate into Western society. Further along in my assigned section of pages Eli Stands Alone returns home with Karen for the Sun Dance Festival. His sister Norma does not say anything directly but she does not approve of his adaption to Western society. She shakes her head at the De Soto rental car which can be seen as a representation of cultural destruction (see description of the De Soto above). Eli doesn’t fit in with his relations anymore and as soon as he leaves “he never looked back” (206). But in the first part of the novel we learn that Eli did come back to his Native culture and “that’s the important part. He came home” (King 63).

The end of Bill Bursum’s pages also mentions how he loves to watch Westerns. This ties in to pages 189 – 193 where Christian asks Latisha “how come the Indians always get killed” (192). Latisha answers that it wouldn’t be a Western if Indians didn’t get killed. Taking this statement at face value it is true, but I think it can be analyzed even further. I think King uses ‘Western’ as a word play. Westerners invaded and colonized North America and defeated the Native people just like the movies depict. That’s the story of colonization played over and over again. Bill Bursum loves them because he has no respect for First Nations history or culture. The Westerns retell and reaffirm the Western perspective after all “if the Indians won, it probably wouldn’t be a Western” (King 193).

I could go on and on about all the connections and allusions in these pages, but I will have to save the rest for another blog post.

Works Cited:

Biography.com Editors. “Buffalo Bill Cody.” Bio. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

Biography.com Editors. “Hernando De Soto.” Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

“BURSUM, Holm Olaf.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. New Mexico State University, n.d. Web. 27 Mar. 2016.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Pueblo Indians.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Nov. 15. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.”Canadian Literature 161.162 (1999): 140-72. 1999. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

“The Grand Council of the Crees.” (Eeyou Istchee) Cree Regional Authority Environment Cree Legal Struggle Against the Great Whale Project. The Grand Council of the Cree, n.d. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto, Ont.: Harper Perennial, 2007. Print.

Marshall, Tabitha. “Elijah Harper.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 31 July 2013. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

“Navajo Legend – Changing Woman.” Native American Art. N.p., 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2016.

Power, Chris. “Baddies in Books: Captain Ahab, the Obsessive, Revenge-driven Nihilist.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 30 Oct. 2014. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.

Welker, Glenn. “Coyote Stories/Poems.” Coyote Stories/Poems. N.p., 19 Nov. 2015. Web. 28 Mar. 2016.