Pages 174 – 186

Please note that as I have chosen a section with overlapping narratives, I have opted to pull each narrative out into their own section. Hence, why the page numbers appear to overlap drastically.

Alberta, Pursuing a Baby (Pages 174-179)

Alberta is determined to have a baby, and considers Artificial insemination. (175) Worried that the experience would be too similar to what she had seen of cows going through the process, she decides to gather information about it, but through cursory research is only able to find places that inseminate animals. The further she dives in to learn about this process, the more bureaucracy and push back she receives. (176) Throughout the course of the ~15 month process outlined in this chapter, Alberta faces aggressive, round-robin operator transfer loops; road blocks in the form of morality clauses in clinic procedures; (177) outrageous and inaccurate waiting periods; (178) canned responses at her inquiries; agents at these clinics telling her “If I got [a form] like that, I’d be tempted to toss it out and forget the whole thing;” and departments not recording notes or communicating with each other, leading to dead ends in support. (179)

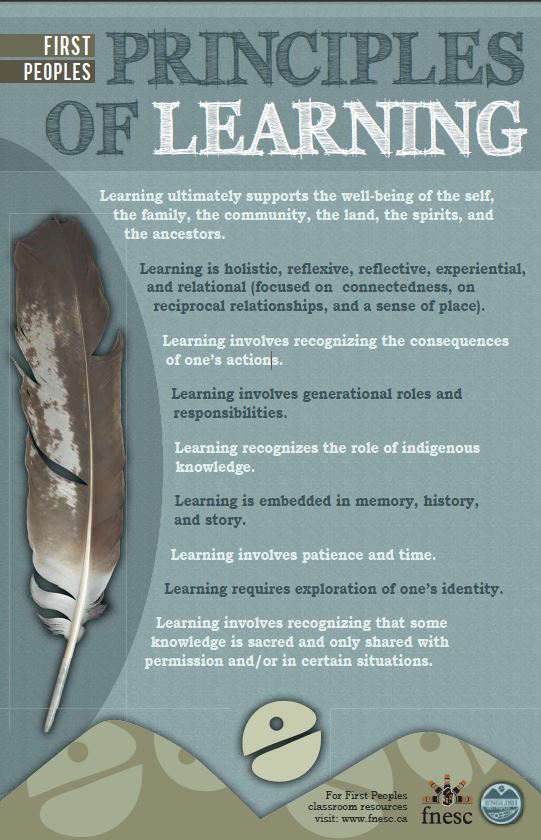

This whole saga highlights the Kafkaesque processes of bureaucracy that Alberta faces in the laws surrounding colonized healthcare, specifically reflecting relentless bureaucracy within the process of providing healthcare to indigenous communities, much of this bureaucracy and inaction echoed in the pages of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 calls to action.

Alberta, Westerns (Pages 175-179)

This segment of the book discusses how Westerns misrepresent indigenous people. Throughout the history of film in North America, Indigenous and Native American peoples have been represented in deeply dishonest and damaging ways. The common practice in these films to cast white actors in brown make up to play native characters, made it clear that the interest in having indigenous characters in these films was not with the indigenous people, these characters represented. Further, the often ‘savage’ description of the natives in the stories, or otherwise overly romanticized versions of ‘Native Warriors’ or ‘Indian Princesses’ created a representation of indigenous people as non-characters within the story.

Alberta arrives at her room at the Blossom Lodge, turns on the tv searches the TV for something to watch. (174-177) The only thing that is on is an old western, which fills her with disgust. While watching a white woman being held captive by an Indian — a captivity narrative common in older films about native and settler conflicts — she ponders what to get Lionel for his birthday. (178-179)

Charlie, Westerns (Pages 180-185)

John Wayne was a very popular actor and filmmaker who’s career spanned from the silent era, into the 1970s, acquiring 179 roles. His significance within this book and especially this passage is that a large number of his most popular films were westerns. Specifically westerns that pitted white men against native Americans, often painting the latter as savage warriors who cause problems for and initiate aggressions against the settlers. Even more troubling are the harsh racist views that John Wayne held and openly shared throughout his career.

Despite this dark history, Charlie seems to have a begrudging but passive nostalgia for Westerns. (182) Unlike Eli, who has an open fascination with western novels and movies within this book, Charlie’s interest in and knowledge of the films seems to mostly come from his father’s involvement in them.

Portland’s Past (Pages 180-186)

Charlie’s father, Portland, moved away from Hollywood with Charlie’s mother, Lilian, when she became pregnant. (180) During this time he worked for the band council and shared is knowledge of working with horses with Charlie, and the local kids. When Charlie was 15 Lilian got sick and died, and Portland, in grief, stopped going to work.

Portland mostly stayed home and fixed things, but then began watching television and falling deep into nostalgia. (181) He would watch old westerns and retell his memories to Charlie of working on some of these sets. He told Charlie about his friend C.B. Cologne, who was an Italian actor friend of his that would get all of the best Indian roles in those movies. This act of hiring non-indigenous actors to play indigenous roles was incredibly popular in these old movies, often persisting into the present.

Portland tells Charlie all about his adventures with the “Indian” stars of the day:

- Sally Jo Weyha

- Polly Hantos

- Frankie Drake

- Sammy Hearne

- Johnny Cabot

- Henry Cortez

- C.B. Cologne

- Barry Zannos

Notably, where the men mentioned in this list of actors are all named after explorers from Europe who came to colonize the americas, the women are named, instead, after historical indigenous women who were enslaved by European settlers and helped them in their quests. Sally Jo Weyha is named after a common mispronunciation and misspelling of Sacagawea who helped the Lewis and Clark expedition in establishing trade with the Shoshone. Polly Hantos, is similarly named after Pocahontas, the nickname of a native girl named Amonute from the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia in the 1600s. Amonute became famous after reportedly ‘saving’ explorer John Smith from what he described as an execution, and allying with him and the European colonizers. I use careful language here, as this account is heavily disputed, and yet has been routinely reenforced and re-popularized by the deeply problematic film depictions throughout the 20th Century, more recently by the 1995 Disney movie, Pocahontas.

This division among gender within these characters serves to highlight the segregated roles that these actors would have had within the narratives of these films. Where the men are driving the action, the women are in place to support the ‘explorers,’ or else be routinely misunderstood.

After showing Portland and Charlie to the studio and introducing Portland to people in the industry, CB suggests finding some work at a steakhouse they know called Remington’s, seemingly named after Frederic Remington, a western-style painter from the old west who had a tendency to paint natives in a stereotypical manner. (185) CB later mocks Portland’s protest by suggesting it was “better than Four Corners,” a burlesque club that offers entertainment in the form of painfully stereotypical native performances. The name “Four Corners” seems to be ironic, referring to Navajo and Ute land where the borders of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona meet. This cross section of different states, converging on native land, with intersecting cultures is heavily contrasted by the flat, dark, tacky, and harmful portrayal of “Princess Pocahontas” being “captured” by a “savage” that is later depicted in this book. (211)

“Adoption Myths.” Canada Adopts, n.d., https://www.canadaadopts.com/hoping-to-adopt/adoption-myths/King, Thomas. “Green Grass Running Water” HarperColins Publishers, 1993.

Buckley, Jay H.. “Sacagawea.” Britannica, 3 Feb 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sacagawea accessed 29 Mar 2021

Duca, Lauren. “A Brief History Of White Actors Playing Native Americans.” Huffpost, 13 Mar 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/white-actors-native-americans_n_4957555 accessed 29 Mar 2021

Flint, Valerie I.J.. “Christopher Columus.” Britannica.com, 11 Feb 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christopher-Columbus accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Four Corners Monument.” Utah.com, n.d., https://utah.com/four-corners accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Giovanni da Verrazzano Biography.” Biography.com, 2 April 2014, https://www.biography.com/explorer/giovanni-da-verrazzano accessed 29 Mar 2021

Gouldhawke, Mike. “The Failure Of Federal Indigenous Healthcare Policy In Canada.” Yellowhead Institute, 4 Feb 2021, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2021/02/04/the-failure-of-federal-indigenous-healthcare-policy-in-canada/

“Hernán Cortés.” New World Encyclopedia, n.d., https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hernán_Cortés accessed 29 Mar 2021

“John Cabot Biography.” Biography.com, 2 Apr 2014, https://www.biography.com/explorer/john-cabot accessed 29 Mar 2021

Mackinnon, C.S.. “Samuel Hearne.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol 4, n.d., www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hearne_samuel_4E.html accessed 29 Mar 2021

Mansky, Jackie. “The True Story of Pocahontas.” Smithsonian Magazine, 23 Mar 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-pocahontas-180962649/ accessed 29 Mar 2021

O’Dea, Meghan. “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Has a Race Problem.” Medium, 7 Mar 2015, https://medium.com/@emmieodea/the-unbreakable-kimmy-schmidt-has-a-race-problem-4465102f3173 accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Pocahontas Was a Mistake, and Here’s Why!.” YouTube, uploaded by Lindsay Ellis, 16 Jul 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ARX0-AylFI

Price, David A.. “Pocahontas.” Britannica.com, 25 Feb 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pocahontas-Powhatan-princess accessed 29 Mar 2021

Rosenberg, Eli. “’I believe in white supremacy’: John Wayne’s notorious 1971 Playboy interview goes viral on Twitter.” LA Times, 20 Feb 2019, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-john-wayne-playboy-interview-20190220-story.html accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Sacagawea, Sakakawea or Sacajawea?.” Sacagawea Historical Society, n.d., http://www.sacagawea-biography.org/sacagawea-sakakawea-or-sacajawea/accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Sir Francis Drake.” History.com, 9 Nov 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/sir-francis-drake accessed 29 Mar 2021

Tavare, Jay. “Hollywood Indians.” Huffpost, 18 May 2011, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/native-american-actors_b_846930 accessed 29 Mar 2021

Treuer, David. “‘The Searchers’ by Glenn Frankel falters in its portrayal of Native Americans.” Chicago Tribune, 22 Feb 2013, https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/books/ct-prj-0224-searchers-glenn-frankel-20130222-story.html accessed 29 Mar 2021

“Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf Accessed 29 Mar 2021.

Vassar, Shea. “‘The Searchers’ Makes a Joke of Native Women.” Film School Rejects, 20 Aug 2020, https://filmschoolrejects.com/the-searchers-native-women/accessed 29 Mar 2021

“What makes something “Kafkaesque”?.” YouTube, Uploaded by TED-Ed, 20 Jun 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wkPR4Rcf4ww

(76)

(76)