Two years ago in the summer of 2012, I visited the Army Museum and paid particular attention to the exhibition of the two world wars. At the time, modern history became exceedingly interesting to me. But of course, then, I was naive about what history was. Now, after my second year at UBC, being familiar with “the historian’s craft” and having explored the question of what is history, my redux at this exhibition has not only been reflection of my own growth of understanding the discipline but also a consciousness of being able to interrogate texts for which historical narratives are written, organized and compiled.

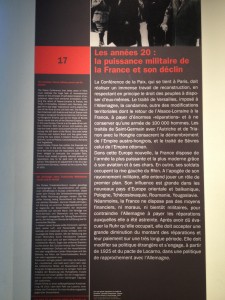

Of course, this is a museum in France; thus my primary question is: How does an author write about the events of the first half of the twentieth century? What information is being emphasized, chosen to be included, omitted, briefly highlighted? These subtle intricacies explain the sorts of intentions, motivations and perhaps political agendas that the author either unconsciously or intentionally strives to pursue.

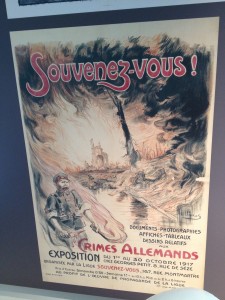

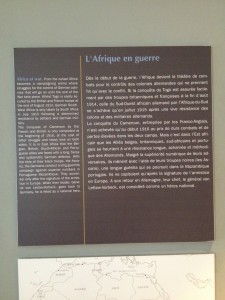

With a fresh understanding of E.H. Carr and Robert M. Stein’s exploration of the interaction between the historian and their facts as well as the linguistic turn which implemented new strategies of literary criticism, I read carefully the descriptions/histories written by the authors/editors of the museum. Whether it be surprising or not, French colonialism, imperialism and its “scramble for Africa” was depicted solely through propaganda posters of rallying its colonial peripheries to participate in war and fight for the Empire’s cause. Though I was not expecting a full holistic description of the social ramifications of European colonialism within marginalized colonies, I found it quite disturbing that the museum elected to make no mention about it. Instead, the average spectator would instead leave the museum with the impression that Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany were the defects of this so-called picture-perfect, “absolutist” history of the world, given that the ambiance within which the two countries were exhibited had a deliberate feeling of darkness, evil and a sense of blame for the casualties of world war two.

Despite endless examples, the notable ones include: The causes of War and who was to blame; the omission of other genocides (other than the holocaust) and civilian tragedies that were committed by the “Allies”; and the deliberate inclusion of adjectives and adverbs to distort certain events, etc.

Two years ago, I read texts uncritically, absorbed information within questioning its origins and believed in truth claims from its face value. Rather than be judgmental of the museum’s authorship, it is necessary to be aware that popular history is, from my understanding, a commonly present pursuit not only in newspaper articles, magazines, but now, also in museums.