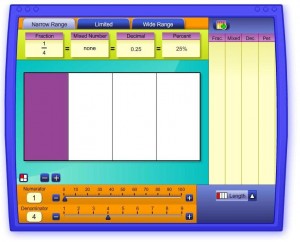

In their investigation into the effectiveness of computer simulations, Finkelstein et al. (2005) concluded that “the conventional wisdom that students learn more via hands-on experience is not borne out by measures of student performance on assessment of conceptual understanding” due to their findings that “properly designed simulations used in the right contexts can be more effective educational tools than real laboratory equipment, both in developing student facility with real equipment and at fostering student conceptual understanding”. Providing students with opportunities to explore concepts in a variety of contexts enriches the learning environment and diversifies instruction to better meet student needs. In the mathematics lesson below, the concept of fractions is embedded in inquiry-based activities to help students visualize this concept while exploring selected interactive applets. Reflection plays a key role in the intended abstraction as a means of guiding students through a process of self-assessment to better understand their conceptual understanding.

In their investigation into the effectiveness of computer simulations, Finkelstein et al. (2005) concluded that “the conventional wisdom that students learn more via hands-on experience is not borne out by measures of student performance on assessment of conceptual understanding” due to their findings that “properly designed simulations used in the right contexts can be more effective educational tools than real laboratory equipment, both in developing student facility with real equipment and at fostering student conceptual understanding”. Providing students with opportunities to explore concepts in a variety of contexts enriches the learning environment and diversifies instruction to better meet student needs. In the mathematics lesson below, the concept of fractions is embedded in inquiry-based activities to help students visualize this concept while exploring selected interactive applets. Reflection plays a key role in the intended abstraction as a means of guiding students through a process of self-assessment to better understand their conceptual understanding.

| Illuminations Lesson for Fractions (click link above for lesson) |

Rationale

By Grade 7, students are expected to have a basic, but solid, understanding of fractions so that they can proceed with more in depth explorations of relationship comparisons and eventually addition and subtraction operations. Unfortunately, this is often not the case and measures need to be taken to assist students’ conceptualization of fractions in preparation of their extensive use in math strands in successive grades. Much of the problem seems to lay with students’ misconception and simplification of fractions down to sets of rules to be committed to memory creating inaccurate mental models. It’s not surprising then that they are frequently unable to adapt strategies they have used in one context to fit a new situation. Their knowledge of fractions remains superficial and does not lead them to a deeper understanding of what fraction symbols communicate as a representation of a whole. When learning abstract concepts, such as fractions, students must understand the fallacy of focusing on memorization as it “leads to ‘inert knowledge’ that cannot be called upon when it’s useful” (as cited in Edelson, 2001) resulting in a poor or non-existent transfer of skills.

Using Illuminations activities provides students with a “variety of visual cues in the computer simulations [to] make concepts visible that are otherwise invisible” (Finkelstein et al., 2005) or at least more difficult to visualize. When integrated into an inquiry-based framework, they can be used to enhance students’ abstraction of fraction concepts while promoting the acquisition of adaptive expertise and thinking skills.

Intertwining the constructivist principles of the Learning for Use framework and T-GEM instructional model provides and impressive foundation for math explorations. The GEM cycle stages of Generate – Evaluate – Modify are complemented by the 6 tenets of LfU, motivate, elicit curiosity, observations, knowledge construction, refine and apply. While collecting information and generating ideas, curiosity and motivation are provoked as students realize what they do not yet know, but need to in order to be able to complete the task. Through key observations, students construct knowledge as they begin to evaluate their assumptions around relationships between variables. As students work to modify their original theories, they need to refine and apply new understandings that have arisen from their investigation. Applications of the LfU and T-GEM frameworks to instructional design presume that overlaps in each of the stages will occur as they both involve a cyclical process of exploration and inquiry. In fact, several cycles may be needed due to the incremental nature of learning; however, the order of the stages remains a critical factor. In the lesson outlined above, two complete cycles of T-GEM and LfU can be observed.

British Columbia Grade 7 Math Learning Outcome (Number – A7)

- compare and order positive fractions, positive decimals (to thousandths) and whole numbers by using

- benchmarks

- place value

- equivalent fractions and/or decimals

Comparing percent to fractions and decimals is a Grade 6 outcome, but by Grade 7 this is consistently not understood well so it needs to be re-taught in preparation for Grade 8 expectations with percent (greater than 100% and fractions of percent between 0 and 1) providing students with a more substantive opportunity to understand the overriding relationships between all three values; therefore, in this activity, this Grade 6 learning outcome will be reinforced as an integral component of the task.

Grade 6 Math Learning Outcome (A6): demonstrate an understanding of percent (limited to whole numbers) concretely, pictorially, and symbolically.

Before beginning lessons involving self-directed exploration of Illuminations activities, students must possess sufficient background knowledge to prepare them for success with the simulation activity. If the expectations for student learning are high given their current context, they will have difficulty navigating the activity (Kalyuga in Srinivasan, S. et al, 2006) and finding the necessary motivation to learn what they need to know to be successful. In this scenario, essential prior knowledge includes an understanding of:

- numerator, denominator, common/proper fraction, improper fraction, mixed number, whole number, simplest form, equivalent fractions, multiple, factor, benchmark fractions/decimals/percents, addition equations equaling 1 whole, decimal place value (tenths, hundredths), parts of one, relating fractions to decimal place value, percent

Along with having prior knowledge, students must be able to access and activate it; therefore, the initial introductory task is intended as a revision of fraction concepts and relationships, which become essential elements, within the subsequent scaffolded activities.

(This post serves as further reflection on the application of knowledge representation and information visualization as it applies to my future personal practice and includes the alternate activity requested in lieu of directly related papers on the use of Illuminations)

References

Edelson, D.C. (2001). Learning-for-use: A framework for the design of technology-supported inquiry activities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching,38(3), 355-385. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1098-2736%28200103%2938:3%3C355::AID-TEA1010%3E3.0.CO;2-M/abstract

Finkelstein, N.D., Perkins, K.K., Adams, W., Kohl, P., & Podolefsky, N. (2005). When learning about the real world is better done virtually: A study of substituting computer simulations for laboratory equipment. Physics Education Research,1(1), 1-8. Retrieved April 02, 2006, from: http://phet.colorado.edu/web-pages/research.html

Khan, S. (2007). Model-based inquiries in chemistry. Science Education, 91(6), 877-905.

Srinivasan, S., Perez, L., Palmer, R., Brooks, D., Wilson, K. & Fowler, D. (2006). Reality versus simulation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(2), 1-5

After reading the articles this week, I find myself contemplating GEM in my planning … a lot. I am excited to try and implement this model of inquiry as it seems to be what I’ve been looking for. While I think I have been incorporating aspects of it already, it has given me a better foundation to reflect on my efforts to help my students develop key processes of inquiry, not just in science and math either … everywhere. I realize I need to put more effort into using “modeling and inquiry [to] facilitate the development and revision of abstract concepts” (Kahn, 899) in my classroom.

After reading the articles this week, I find myself contemplating GEM in my planning … a lot. I am excited to try and implement this model of inquiry as it seems to be what I’ve been looking for. While I think I have been incorporating aspects of it already, it has given me a better foundation to reflect on my efforts to help my students develop key processes of inquiry, not just in science and math either … everywhere. I realize I need to put more effort into using “modeling and inquiry [to] facilitate the development and revision of abstract concepts” (Kahn, 899) in my classroom.