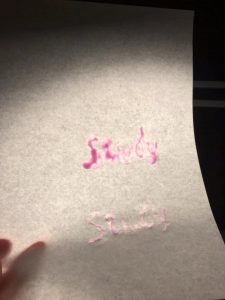

To be honest, I initially thought making potato stamps would be a piece of cake. The video didn’t seem to be difficult to follow. But when I started to carve the potato, I realized it takes more much effort than it seems to take. It was especially difficult to carve the curved part of the letter without breaking other letters. It took me several attempts, two potatoes, and two hours to finish the stamp. After I used it on a piece of paper, I realized I did something stupid and awfully wrong: I didn’t reverse the letters so that the stamped letters are reversed. I had to flip the paper and see through it from the reverse side to have the view of my word “Study”. The whole process was not as interesting as what the video showed at all. Applying the fabric paint on the potato stamp was challenging as well, probably because I didn’t have a brush. The paint I bought says that I can just squeeze the paint on the surface with the tip it includes. But I don’t think that worked. The paint was uneven and made my stamp even worse. This activity provided me a brand-new perspective on writing and printing. I didn’t expect printing to be so difficult since Gutenberg’s idea sounds very straightforward to me. After this activity, I realized the difficulty to carve woods and even metals in Gutenberg’s printing press innovations. I also realized how easy writing is compared to printing using carved metal blocks. However, writing is impossible to be standardized and mass-produced. As the podcast “The Printed Book: Opening the Floodgates of Knowledge” suggested, books produced by hand-copying are very costly in terms of labor and time, prone to mistakes, and very expensive. Printing using carved metal blocks, although extremely difficult, provided a massive amount of space or media for knowledge transmission.