A bit of a digression…

I decided I would give this potato printing activity a try because I regularly write with a pen / pencil on paper, and am very aware of how much more I remember when I write things down in cursive form compared to mechanically typing into a digital device. I am in the camp that believes part of being literate means knowing how to write cursively (hand-written text), not just typing into a keyboard. I know digital writing, even for taking notes in class, is ubiquitous but if we agree with the argument that writing changed human cognition, this was based on the hand-brain connection of cursive writing, not typing mechanically into a computer. Yes, this mechanization of writing is all around us, and I appreciate the accuracy and efficiency of the printed word, and I must type up my ‘formal’ essays and any text I want to share digitally, but I don’t feel the personal connection or find it as easy to remember, in comparison to the text I write with my own hand. I’m also old enough to have used a typewriter in the first years of my undergrad, and felt the same way about the text I created, or perhaps even less attached to that text (because I hated typing on a typewriter – so many errors, WhiteOut and corrective tape!). So, to end this digression, I chose to try to find out how difficult it would be to create a printed word with potato stamps because I don’t remember ever trying to print something on to a page.

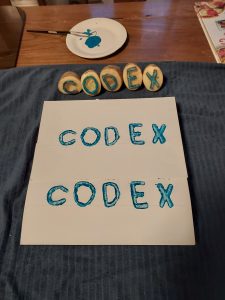

Preparing, Crafting and Producing my word: CODEX (I wonder how many others chose the same word? 🙂

Preparation: After watching the Youtube video a few times, I purchased 6 big cooking potatoes, found a fruit knife and a steak knife (in case I needed different types of cuts?), raided my daughter’s art supplies boxes for: 2 pieces of good art paper (heavy weight, made for painting and printing), a red marker, a small-tipped paintbrush and a tube of blue acrylic paint (I realized water colour would not work with a wet potato). Put everything on to my coffee table and began my work at 4 pm, Oct 1.

Crafting: Following the instructions on the video was fairly easy, but I found it a challenge to get a marker that would deposit its ink onto the potato. Something about the mix between liquid that oozes from a cut potato and any kind of marker I could find in my house caused the ink to stop producing. Long story short: I went through 10 markers (about 2 for each outline) before finishing the outlines for my five letters! The other challenge was to try to create letters to that were: 1. approximately the same size (C being the same size as O, being the same size as D, etc.), and 2. identifiable as the letters I intended them to be (the difference between a D and an O is not as big as I thought before trying to create these stamps).

My process to keep everything similar across my prints was to go through each step at once, so once I cut up all my potatoes into halves, I outlined all my letters in one round (approximately 30 minutes). One letter was outlined onto one potato half (as instructed). I then began cutting out each letter, and progressed from the first word, beginning with C and ending with X (for CODEX). The cutting of each letter was the most challenging part of this process for me because I wanted to create a large enough space on each potato stamp so ink could saturate it then transfer later to my paper when I printed it. This process took me over 60 minutes. I have experience using chisels and files to create stone and wood sculpture, so I know about the ‘give’ of a substance when trying to create or release a shape. In fact, I think if I had tried to create wax or dry clay versions of these letters as I imagine medieval monks or scholars (or accountants!) might have done, I believe there would have been more room for error and more ‘give’ to these substances. Potatoes are wet, mushy and fairly unforgiving when trying to create anything more than a simple shape (for me, anyway). So, I chose to simplify the crafting process by creating the upper case versions of each letter in CODEX. I didn’t choose letters for this word because they were simple, but definitely felt that using the larger upper case versions would enable me to create more long, straight lines that were easier to carve out.

Producing: After all my letters were carved on their 1/2 potato wedges, I moved to our kitchen table, placed a hard box under each of my pieces of paper, then using a ruler and a pencil, mapped out on each piece of paper where I would put each stamp to create the word so the word would be relatively identical on each paper. The final stage was to paint each letter with the blue acrylic paint (unaffected by the potato liquid luckily!) and place the stamp in its correct spot. I began from the left to right, first I painted then stamped C on to one paper, then repeated the process with C on the second paper. I followed this process for all of my stamps to create the word. I noticed the pressure of my hand made a big difference in how much paint and even the size of the outline of some letters. This was very difficult to control! This affected my O and E prints. This process was fairly quick, perhaps 15 min.

Reflection: I can’t imagine trying to create cursive script stamps on potatoes, or worse still – Chinese traditional characters on potato stamps! Certainly I can see that if words and books are an extension of the human mind, an external hard drive for our brains, at the level of creating stamps to illustrate the mechanization of writing, the person who creates the stamps is not very related to the person who writes the text to be printed. Or at least, the time and effort to create a stamp for each letter would distract or dismay most writers! Instead, as a result of this task, I have a richer understanding of why before Gutenberg’s creation of his printing press, only those trained to write (which involved literacy) or people with a great deal of time on their hands who could carve stamps would have the opportunity to create or document much writing. Gutenberg’s printing press also allowed whole words to be printed onto a page, rather than having to painstakingly press each letter, one at a time. This would have reduced the inconsistencies and potential inaccuracies (what if a printer forgot to put the ‘letters’ in the correct order when printing?). Also, it’s so interesting that Gutenberg’s original typefaces were cursive!

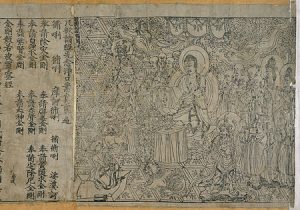

Certainly the mechanization of writing was one major step that changed history, and has made disseminating information more efficient and accurate. We are now in the age of digital communication where the printing press is almost going out fashion in the push for everything to be shared digitally. It’s an interesting mental activity to learn how difficult it would be to create stamps that could be used to create printed words. This makes me look at the Diamond Sutra print with more interest, for one because it is obviously a beautiful example of what is acknowledged as the oldest dated printed book (as a scroll, not a codex). But also I learned that this sutra is a Buddhist text, which according to Buddhist belief copying images or words of the Buddha would have been seen as a good deed, and it is likely that monks would have unrolled this sutra and chanted the sutra out loud, which links back to my previous ramblings in Task 3 about the importance of oral literacy.

From the Smithsonian Magazine (digital version!), I learned one quote from the Diamond Sutra about the passage of life that is timeless (translated by Bill Porter, or “Red Pine”):

So you should view this fleeting world –

A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream,

A flash of lightening in a summer cloud,

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

It was part of the oldest printed book, but would this be better spoken or read?

ping cao

October 23, 2021 — 11:36 pm

What caught my Diamond Sutra part because I don’t recall a famous quote related to the English version I saw in your post, so I did some digging. Here is what I find, the Chinese version of Diamond Sutra was “一切有为法,如梦幻泡影,如露亦如电,应作如是观” (金刚经 第三十二品 应化非真分).

Both are translated by the meaning, and both were using a poem format. It is amazing how both English and Chinese translators decided to translate Diamond Sutra with the most beautiful expression they could find in the language. It is also challenging to understand if you have no references.

To answer your question, I think printed text and the “spoken or read agree” proposed by your both have their advantages. On the one hand, Diamond Sutra is the record of conversations between Tathagata Sakyamuni and the elder Subhuti and other disciples when he was alive, so reading would make sense to reenact that scene. On the other hand, Diamond Sutra is so rich and deep in meanings, so I agree with Hass’ argument that “written texts foster contemplation, analysis, and critique” (2013, p9), and it also makes sense for us to view the written text to analyze what are the multilayers of meaning.

atrainor

December 4, 2021 — 11:57 pm

Hi Delian,

I very much enjoyed your “Little bit of digression…” and share your value of hand-written cursive. I enjoyed this module’s video “Upside down, left to right: a letterpress film”, and connected to how “cursive”, like forms of pressing, might now be seen as an art.