I’m David Jalsevac, an English Language and Literature teacher at Victoria Shanghai Academy in Hong Kong. What follows is my contribution to the “What’s in my bag” exercise, completed on January 19 2025.

This picture was taken after returning from the Hong Kong Public Library after going on a marking tear marking student exams. These are the last formal in-school exams for Year 12 before they write their IB exams. However, because I teach them tomorrow, I was marking Year 11 papers, these are their FIRST in-school formal exams of the Diploma Programme.

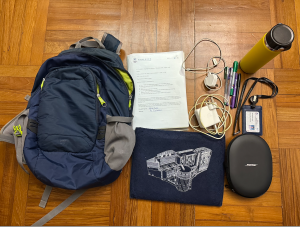

The pens in purple, green and black ink of various thicknesses are significant – they are chosen in different colors to contrast with the student’s blue or black. The best pen I’ve found is a uniball Signo 0.7 which feels smooth to write with and does not bleed excessively through the paper like the thicker zebra two-sided markers.

My half-full hydroflask water bottle bears my last name printed in permanent marker by my mother – I have to keep reminding myself to drink during the workday and end up not doing so at all. I took one sip as I left the library today.

My laptop rests in a felt case bearing a digitally rendered image of our school campus – one of hundreds distributed when our new building wing opened. There’s something telling about seeing these identical cases everywhere on campus, each teacher toting the same mechanically reproduced image of our shared space. The usual accessories trail along: laptop charger, iPhone cable, and my Bose Quiet Comfort headphones that help maintain focus during marathon marking sessions.

My staff identity hangs from a replacement lanyard (the original lost en route to ball hockey) – a white digital card with a laminated overlay. The overlay displays my photo, name, and role as “Secondary Teacher,” with the school’s identity presented bilingually in English and Traditional Chinese, accompanied by our accreditation markers (IB, CIS, NEASC). This card mediates access to the school’s electronic gates and secondary staff room, and lets me print at any of the school’s printers.

Colleagues view me as an AI enthusiast, but I see it more as a practical compulsion, no different from any other teacher’s methodological preferences. A deeper tension lies in my linguistic limitations – despite two decades of intermittent life in Hong Kong, I remain stubbornly monolingual. In our English-privileged educational environment this rarely creates practical issues, but it marks a personal shortcoming I’m acutely aware of.

Speaking of bilingualism, I carry a secret shame that I’ve lived here on and off for over 20 years now and I am still a monolingualist. In the environment I’m in which privileges English above Chinese this doesn’t matter, but they don’t see someone who views himself as linguistically lacking.

The exam papers follow a consistent format: booklet-style papers with front matter covering course details, instructions, and academic honesty declarations. Inside, students analyze a blog transcript, mirroring the structure of the IB Paper 1 exam. Their responses are written on lined paper embossed with our school crest, in blue or black ink.

Text Technologies

Since the most significant contents of my bag reflect my marking practice – the exam scripts, pens, and AI-equipped laptop – I’ll focus on how these tools represent my evolving assessment process.

My marking process has evolved significantly. What began as purely individual analysis has transformed into a collaboration with AI. I feed selections from student scripts into Claude-3.5-sonnet, offering my initial thoughts and seeking validation of my feedback (it is very agreeable). I often get it to adjust its responses to a Year 12 comprehension level. These comments often expand to 1000-1500 words – multiplied across 28 students in two classes, it represents a substantial body of detailed feedback.

Let me share a typical example of how AI assists my marking process. When evaluating a student’s podcast analysis, my initial thoughts often emerge as a stream of questions and potential feedback points:

I basically agree with this analysis

Does she need to be more explicit about linking the point about enjoyment to change, by saying that it makes the listener more amenable to the ideas presented to them

She doesn’t have to say that it is stypical of podcasts to use a conversational tone, that’s kind of robotic – “The text is a podcast, which uses a conversational tone” She could simply mention that THIS podcast is conversational

Shoudl I point here, This analysis is fine, but also consider the conversational dynamic between Robin Chatterjee, how they pass each other off as quite convivial (is there a more Y12 friendly word than that), as though they are long-time friends, which also makes readers more susceptible of the message

She could specify that the phrase “Yeah Right” is a colloquial phrase, the colloquialism creates the informal tone

It’s also kind of robotic that she says “as opposed to “yes, I agree”

Should I give her checkmark when she says – or is it better to say it creates an atmosphere of intimacy/familiarity

Grabbing readers’ attention is superficial – should I say that?

When the student says “nformal tone and enthusiastic language can not only make the podcast more engaging, but also create a positive relationship between the listener and the topic of wealth. – Should I say good connection to the guiding question

This positive interaction gives a positive association with wealth – should I say here Specify that this is Sharma’s expanded concept of wealth, not your garden variety wealth = money kind of wealth

Through AI collaboration, these scattered thoughts transform into focused, student-friendly comments:

“No need to generalize about podcasts – focus on how THIS podcast uses conversation”

“Good observation. You could specify that this is colloquial language, which creates the informal tone”

“Consider also how Robin and Vishen interact like friends – their rapport makes listeners more receptive to the message”

“✓ Good connection to guiding question”

There’s an odd tension in how we approach AI in education. While we encourage students to think critically about technology, there’s still an unspoken expectation that teachers should maintain the illusion of purely human assessment. The IB’s stance remains notably vague and non-committal. I find myself in an odd position – knowing that AI-assisted feedback often provides clearer, more consistent insights, yet feeling pressure to downplay this tool’s role in my process.

While AI assists my process, it hasn’t fundamentally changed my commitment to thorough assessment – I can take up to three to four hours on a single script when needed. But now that time is spent differently. Instead of struggling to articulate feedback, I’m collaborating with AI to refine and perfect it. Even my teaching materials evolve through this human-AI partnership, with Claude helping to shape class discussion slides.

Fifteen years ago, my toolkit would have been simpler – pens, notebooks, but no exam scripts as teaching wasn’t yet my profession. Looking at these tools now – the colored pens, the paper scripts, the laptop with AI assistance – they represent a transitional period in education. While younger students increasingly prefer keyboards to pens, showing the digital shift in progress, there remains something uniquely valuable about the physical act of writing and marking on paper. Perhaps that’s why, even as digital assessment becomes more prevalent, these tangible tools persist in our practice.