History of potato stamps

Potato stamps originated in the early 1900s when North America was seeing an influx of white European settlers and Indigenous peoples wanted to cater to this increased “tourism” by decorating their woven baskets (Made by a Potato, 2022). A cubism art movement was sweeping across Europe and these basket decorating techniques seemed to catch the attention of passing tourists, using vegetables such as potatoes and squash and herbal dyes on ash splint baskets (Bruchac, 2015). Interestingly enough, this practice of weaving and designing baskets emphasized the importance of oral storytelling in Indigenous cultures (connecting to Task 3).

Challenges

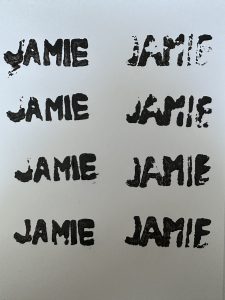

Embarrassingly so, I created the first stamp backward and had to redo it. I had one of those moments where you cannot believe how silly you were…like duh! And then I had another moment where I realized that maybe each letter needed to be on its own potato and that we needed five stamps and not two stamps of the full word. But alas, I’ll speak to what I know and did in this circumstance.

Time taken

I think from the very beginning (full potato) to stamps on the page, my guess would be about 25 minutes. I used a kitchen knife to cut the potato in half and cut out the letters, I kind of thought after that it may have worked better if I used my art knife (but we’ll never know now). I tried to use multiple writing tools to write the letters on before cutting, but nothing seemed to stick (sharpie, marker, pencil), so I had ultra-light markings to follow when cutting.

Letter choice

The curves of the J and the inside space of the A were particularly challenging to cut. I found the little space I had to work with it made all of the letters difficult to define and refine, the M and the E had a lot of middle spaces that I was worried I would chop off one of their “limbs”.

Mechanization of writing

I thought it was a lot of fun to do a hands-on activity, it was at times calming and almost meditative, this was a first for me in the program. However, my stamps look like garbage, they took quite some time to create and prepare, and they made quite a mess with potato chunks, juice, and paint. I had read somewhere that some people have used cookie cutters to create shapes in the potato, pressing it into the open half and cutting around – this sounds like a fun way to do crafts with kids as well. This may be what I reserve this for, a fun activity to do with kids around the holidays to make cards and build some motor skills along with creativity.

I do recognize that historically it may have been a low-cost alternative to produce a repeated pattern or message, so it would have been more efficient and quicker than writing or drawing by hand. Appreciatively it was an important step towards more advanced practices and technologies for printing and the way we share information.

As I watched the short film on letterpress technology I almost found it such a beautiful art form. Efficient, no, not in this day and age as it is time-consuming and the actual technology of the press is so dated it is hard to find and/or replace parts, but an enchanting operation. Once textual bodies are all perfectly pieced together, it is impressive how fast it does in fact make copies with the rolling mechanisms. An acceleration of 200 pages to 768,000 pages an hour is a fascinating statistic the printing press holds, it is no wonder it transformed societies (Innis, 2007). My work of potato art was not so transformative!

References

Bruchac, M. (2015, May 5). Potato Stamps and Ash Splints:

A Narrative of Process and Exchange. https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/potato-stamps-and-ash-splints/

Danny Cooke Freelance Filmmaker. (2012, January 26). Upside down, left to right: A letterpress film [Video]. YouTube.

Innis, H. (2007). Empire and communications. Dundurn Press.

Made by a Potato. (2022, November 4). The History of Potato Stamps. https://madebyapotato.com/blogs/news/the-history-of-potato-stamps