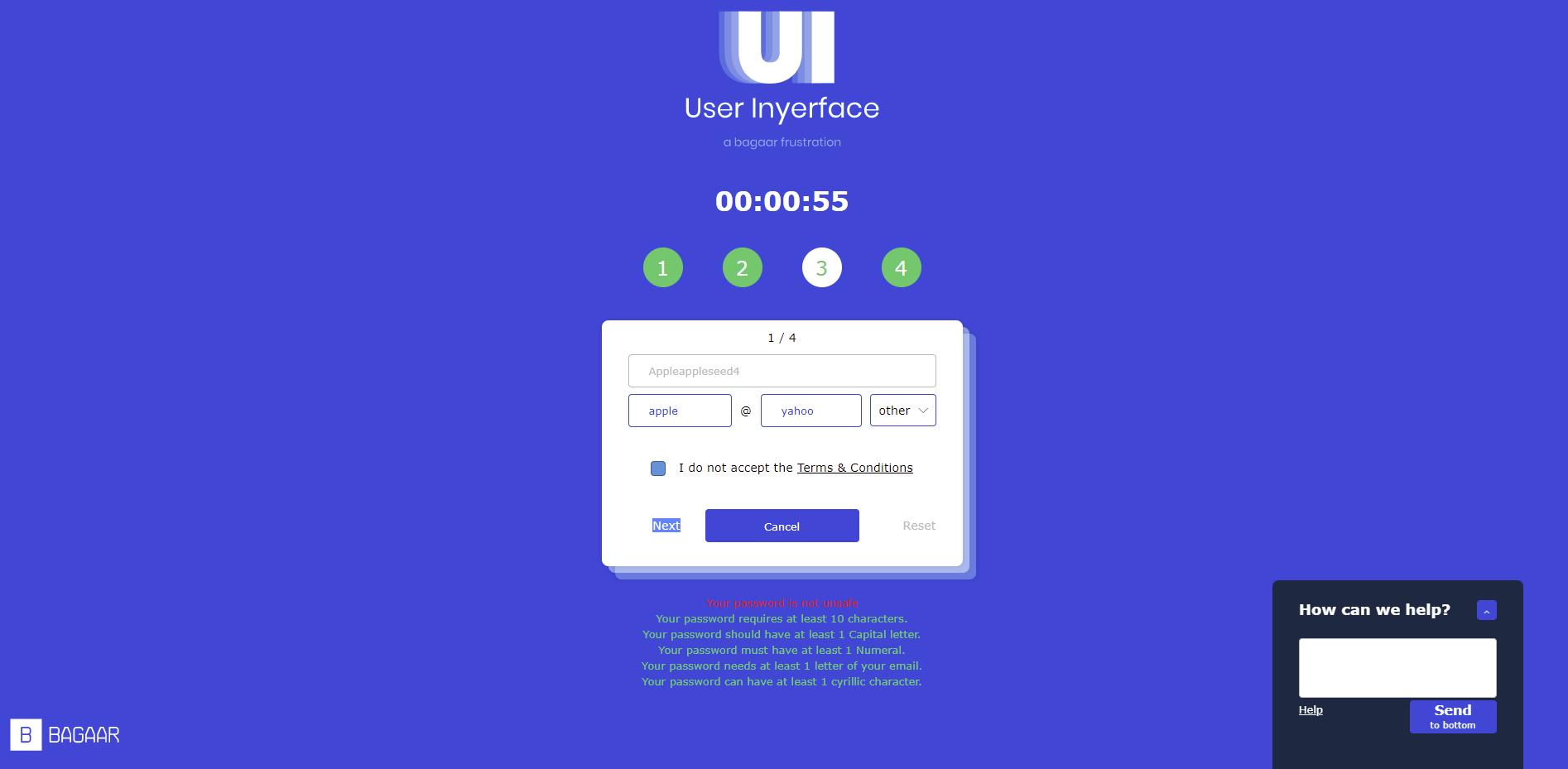

When I played the User Inyerface game, I felt proud to have gotten to the forth page! Unfortunately, I was using a new screen shot app that didn’t autosave, and I was left with only the very first image I took with my old screen capture tool. Let’s just call this photo, “The beginning of frustration”.

Interacting with this interface reminded me ALOT of how I feel when I try to use Glassdoor.com. When ever I attempt to read any employee reviews of their jobs at particular companies, a shield moves down to cover all of the information. This has forced me to get an account, and even after I did, I was then prompted to enter my salary information before I was allowed to see any of the reviews. As I played User Inyerface, I realized that no matter how much I clicked in the ‘expected’ locations, the actions I wanted to execute did not happen. I continued anyways, as “The problem with addiction is that it deprives the victim of agency, even when an addict understands the potential for harm, he or she cannot help but continue the activity” (McNamee, 2019). Only after many errors did I figure out that I had to arbitrarily click on random places to move to the next screen or to close unwanted pop-ups.

One of the ways my attention was being directed by the interface was through the necessity to make rash decisions based on time. This feeling of hurriedness existed even though the loss of time, indicated by the the pop-up clock and syncopated seconds, lead to no consequence. I was not kicked off, and I never actually ran out of time. What did happen, is that I felt disorientated and continued to click randomly around, just to accomplish something. What that was, I still don’t know. I also entered an email and password with a shared letter, even though I knew that it was the wrong thing to do. I did it merely to move on!

One of the other devices used to capture my attention, was a slow response time. When I chose the option to send the ‘help’ box down to the bottom of the page, it moved very slowly. I stared at it wishing it would go away. When I tried to use the ‘help’ box for actual help, it auto filled my question to some strange word. Maybe it was only put there to collect my data? When I opened the ‘terms of agreement’ window, the scroll bar felt heavy and I had to drag my hand super hard for it to move anywhere. I could see on the side that it was quite long, and this filled me with dread, thinking how much effort it would take to read these terms. Like Harris (2017) mentioned, I was reacting from my lizard brain. From the way I was interacting with this site, it was difficult to know whether or not I was in fight or flight.

When the interface told me that I was almost finished, I felt a mix of relief and disbelief. I spent a little bit longer than I wanted to, trying to choose the correct pictures to prove that I wasn’t a robot. I did this despite the fact that I knew there wasn’t enough circles to indicate my selected photos. Was I choosing the images on the top or the bottom of each circle? I gave this page about 7 or 8 passes, because 1) I am stubborn and 2) I was being persuaded to spend more time on screen (Harris, 2017). In the end I was left wondering if it was all just a rouse, and if there really was a next page, as there were too many ways to interpret each option, and no way out. Tufeki stated that “We know longer know if we are seeing the same information…”(2017). When considering this ‘non-robot validity test’, what do people in other countries see if on the same website. Do they also have to choose between multiple homonyms? If I use glasses to see and someone else uses glasses to drink, would I have to develop a matrix of answers before being able to prove I am human? The promise of a reward kept me clicking.

Harris, T. (2017). How a handful of tech companies control billions of minds every day. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/tristan_harris_the_manipulative_tricks_tech_companies_use_to_capture_your_attention?language=en

McNamee, R. (2019, January, 17). I mentored Mark Zuckerberg. I loved Facebook, But I can’t stay silent about what’s happening. Time.com. https://time.com/5505441/mark-zuckerberg-mentor-facebook-downfall/

Tufekci, Z. (2017). We’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads. Retrieved from (Links to an external site.)https://www.ted.com/talks/zeynep_tufekci_we_re_building_a_dystopia_just_to_make_people_click_on_ads?language=en (Links to an external site.) (Links to an external site.)