For this task, I was asked to come up two speculative narratives suggesting future relationships between education, technology, text, and media. As Dunne and Raby (2013) state, even though most future predictions of this nature are unlikely to come to fruition in a meaningful way, they can still be used “as tools to better understand the present and to discuss the kind of future of future people want” (p. 2). I have presented my narratives in slightly different forms below, with one focused more on presenting a potential new form of writing, and the other examining a subject (Alex) and the ways in which his career and life is being impacted by an increased prevalence of artificial intelligence.

Alternate future #1: TEXTOGRAMS

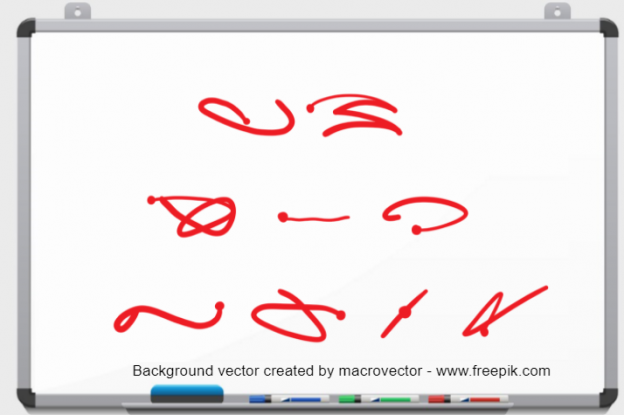

Typing skills for the English alphabet are taught as fluid motions and are studied/recognized as distinct entities in the same way as logograms.

In the year 2031, the majority of writing has gone digital. A decade prior, back in 2021, there was already a shifting emphasis away from handwriting and towards developing strong typing skills. As smartphones got cheaper and cheaper, and students at younger and younger ages were granted access to their own personal devices, new writing skills emerged. Soon, students were doing the majority of their writing simply with their thumbs. As fast as they were (indeed, it could be quite impressive to those non-digital natives) the speed with which they sent messages simply wasn’t as fast as previous generations using computer keyboards. To address that speed deficiency, a group of teachers in Vancouver, B.C. joined together to create a locally-developed texting course called “Intro to swiping – the texts of the future”. What started as a guide to faster texting evolved into an entirely new way of looking at the English language, through the use of logograms (characters representing whole words), similar to what is seen in eastern cultures. Now, alongside courses in typing, the majority of English-speaking countries have courses devoted specifically with learning this new way of texting, as well as the study of the characters (uncreatively called “Textograms”) that have resulted from this new form of writing.

Shown below is a greeting projected onto the board of a typical introductory course teaching Textogram writing. See if you can decipher it, check out the slideshow that helps explain the meaning behind each Textogram. As a minor hint, the dot on each Textogram (aside from for those symbols representing single letter words like “a” or “I”) represents the beginning of the swiping motion required to form each word.

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1CWpYlrQU1ghoxV-GcFHvSd_uFg_KcEWQeP1ZVsrdaEU/edit?usp=sharing

Alternate future #2: PRESCRIPTIVE TEXT

It’s been a tough few years for Alex. With the ever-changing job market due to the rise in automation, he has struggled to find a role that he can stay in long term. He knew graduating with an arts degree might not have been the wisest choice in the current climate, but he just couldn’t see himself sitting behind a computer coding all day – like the majority of his more successful friends. The irony then is that his current role has him working so closely not only with computers, but with the automation that is making him feel so obsolete.

What does he do, you ask? For the last three months, Alex has been working behind the scenes of Google’s latest initiative – Prescriptive Text. Think of the automated replies and autocomplete suggestions you get in g-mail. It’s like if those two features had a baby with the love child of greeting cards and mad libs – thoughtfully worded messages provided for the user without the care and attention previously required for such things. The eventual goal of Prescriptive Text is to allow users to select a set of emotions and general ideas that they want to convey, and in return they are provide with a set of messages they can use. Automatic replies in g-mail are part way there already, but they lack certain levels of human emotion and rely on too many clichéd and painfully obvious stock responses.

Alex’s job is to bring the humanness to the texts being prescribed. In essence, he has been tasked with creating a database of new turns of phrase for both generalized and specific situations so that the artificial intelligence managing the Prescriptive Text doesn’t sound so, well, artificial. Google’s two-fold goal is to have a rich enough database within the next two years (by 2028) that all writing within the Google suite of products will have the option of being written by Prescriptive Text, and that such messages will be near-impossible to decipher from original, fully user-generated content.

With that timeline, Alex knows that his current position is limited. His only hope at extending this position beyond the two-year timeline is to bring something invaluable to the table. This has meant hours upon hours of researching the latest slang and studying speech patterns of different social groups. His hope is that he will snag a position in the smaller contingency group planned to address the changing needs to the database as the English language continues to evolve. His great fear though – one also expressed by others in his department – is, ironically enough, that if Prescriptive Text becomes too widely used, it may slow down the evolution of language to the point that the contingency group is rendered unnecessary.

References

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

James,

Really creative ideas here! I thought your Textogram speculative future was very interesting – I’ve anecdotally noticed a divide in smartphone users who type on a keyboard and magically swipe to create words. I thought it was very creative to appeal to the idea of logograms. Very, very cool. Alternatively, I also appealed to a similar idea in my narrative: where jobs are taken by AI-enabled machines, however, some jobs remain – the ones that do the programming, code the algorithms, and manage the implementations of the machines themselves.

Thanks, Carlo, but I think your Speculative Narratives take the cake when it comes to creativity.

I really like the connections you made to language in both your scenarios, but especially in scenario 2. Scenario 2, reminded me of the pre made report card comments that teachers can use with students. I think it’s very fair speculation that presecriptive text would lead to a static language, and homogenize ideas and style in the written word.

Thanks, Dierdre.

I definitely think that the more we reply on prescriptive text, the less imaginative and personalized our conversations will be. Report card comments is a perfect example of that. I rarely use the pre-made ones because I want more personalization and I feel like they often just aren’t quite the right fit. I always want to tweak enough that it just makes sense for me to write them myself.

Hey James,

Wow, you invented a whole new language system! I really like the creativity behind that one and the connections to the early modules on the invention of text. I suppose in the course, Intro the Swiping, students would be taught the standard way of swiping so that these logograms would appear somewhat uniform between different writers? I imagine that some people would take a curvey route from one letter to the next, while others might take a straight route. It’s a bit like deciphering cursive writing, I suppose, where the letter shapes from writer to writer have differences.

Hi Ying,

Absolutely I think that there would be stylistic variations in the ways that people would write the logograms similar to the way that different people print and handwrite. The true test on whether a student has written a logogram correctly would be to implement the movements on a keypad as see if they result in the desired word. I think within there, there is a lot of room for creativity and variation.