The History of Google Translate

Machine Translation (MT) and discussion regarding its use in language learning dates as far back as the 1980’s (Garcia & Pena, 2011). Today, the application Google Translate (GT) is ubiquitous within these discussions, and for good reason. In celebrating the 10-year anniversary of its 2006 release, GT Product Lead Barack Turovsky boasted of the incredible reach of the application; among the notable accomplishments highlighted were the range of languages the app supported (103), the staggering number of users (500 million+), and the incredible number of words translated daily (100 billion+) (Turovsky, 2016). Originating as a webpage, the Machine Translation (MT) software is now available as a smartphone application for use by language learners and those navigating language barriers in everyday life (Bin Dahmash, 2020). Ever-improving, a new version utilizing artificial intelligence – the Google Neural Machine Translation (GNMT) – was launched back in 2016 (Tsai, 2020). Even before the introduction of GNMT, the grammatical aspect of the app’s English translations would likely have satisfied the minimum language requirements for many English-speaking universities (Mundt & Groves, 2016).

To view the most recent updates to GT, view Google’s official blog.

Affordances of the Technology

To understand the potential impacts of GT within literacy and education, we need to first look at the designed affordances – what is the technology meant to do? Using a variety of input options – typed text, handwritten text, and voice input (including its conversation feature) – GT offers translations along with both definitions and audible pronunciations. It will also allow you to save translations into your own personal phrasebook for future reference, and for a select set of languages (ten at the time of posting this article), the software will create translated transcriptions that you can also save. Probably the most advanced feature to date, however, is the ability to hover your phone’s camera over a piece of text and have a translation superimpose itself over that text using augmented reality.

It should be noted that the level of support and sophistication varies from language to language. Not all supported languages are available to download for offline use, and less in-demand languages are missing certain functionalities. Additionally, due to structural differences between languages, the app works better for some language combinations (like Spanish and Italian) compared with others (like English and Arabic) (Garcia & Pena, 2011; Läubli & Orrego-Carmona, 2017).

Though a robust tool for providing language translations, the original intention of MT systems like GT was not for language learning (Tsai, 2020), much in the same way that dictionaries are not meant to teach literacy but rather act as a supportive resource. However, the current iteration of GT is a far cry from the early MT systems of the 1980s and according to Bin Dahmash (2020, p. 228), “how people utilize the built-in features of the app to fulfill their unique purposes might not match the original designers’ intentions”.

Within Education and Additional Language Literacy

So what are the implications of GT use within education? For starters – barring some unforeseen circumstance – the app will undoubtedly be heavily utilized by language learners for years to come. Anecdotal evidence compiled by Bin Dahmash (2020) in their study of Arabic-speaking English language learners in Saudi Arabia showed that students initially encountered GT through a variety of sources outside of the classroom including online advertisements, search engines, and close relations. Already viewed by students as a valuable resource before entering the classroom, there is no denying the likelihood of the assumption made by Mundt and Groves (2016), that GT “will be used by student writers, either openly if sanctioned by institutional policies or clandestinely if not” (p. 388). With that assumption, they surmise that universities (which can conceivably be extended to include other types of learning institutions) should develop a set of best practices for integration of the technology into language learning, and establish guidelines for acceptable use.

So how are language learners currently using the GT in ways one might deem worthy of promotion and inclusion within curriculum? Before answering that, let us make a distinction between the tasks of learning another language and being able to produce written work in that language. While there is intersection between the two, they can still be seen as different entities needing distinction.

As previously stated, GT translations can be accessed using various modes of unput. Bin Dahmash (2020) noted that within their study, a determining factor for method of input was the length of text, with learners typing in short sections of text by hand, and utilizing their phone’s built-in camera for longer passages. Students in this study also accessed translations using GT’s conversation feature, which would transcribe and translate conversations between two or more parties from one language to another (in this case, between English and Arabic) (Bin Dahmash, 2020). Through use of GT, students have been able to improve their vocabulary, pronunciation, spelling, grammar, and reading (Bin Dahmash, 2020; Tsai, 2020). It should be highlighted however that the extent to which pronunciation is improved may vary drastically depending on the chosen language and whether Google has invested in human recordings of the language, or if a robot-voiced version is provided as a cheaper alternative.

Regarding writing, Tsai (2020) acknowledges the importance that learning to write in a new language has on language learning due to the indispensable nature of how writing shares “feelings, thoughts, ideas, comments and experiences with others,” (p. 1). In a study looking at the effectiveness of using GT to improve the writing performance of Chinese students studying English, Tsai (2020) found that students could benefit from using GT-produced translations as a resource to improve texts initially self-written in English and then edited with the aid of the translation. His study observed both lower – non-English Major (NEM) – and higher-proficiency – English major (EM) – English language learners. He found that both groups were satisfied overall with the provided translations, both groups successfully improved their writing as a result, and there was a noted appreciation among both groups for the opportunities it afforded them for improved vocabulary use. However, he reported that the levels of satisfaction were significantly higher among the lower-proficiency NEM students, and these students expressed a greater willingness to continue using GT in their writing.

A similar study was conducted by Garcia and Pena (2011), looking at whether MT could aid in the development of writing skills for English-speaking beginner/early intermediate Spanish language learners. Their study worked with a GT-supported program that allowed users to write in English, view the real-time translation of that writing in Spanish, and then perform both pre-edits (to the English) or post-edits (to the Spanish) in an effort to improve their Spanish writing output. Unsurprisingly, they arrived at a similar conclusion, suggesting that “MT helps learners to communicate more, probably in a way that is inversely proportional to their actual mastery of the language: the lower their mastery, the greater the help provided by the MT draft” (Garcia & Pena, 2011, pg. 478).

As suggested by Tsai (2020), “Google Translate can play a role of a second ‘audience’” (p. 15) for language learners as they practice their writing, providing them with advice on both word usage and sentence structure. In language classrooms where students may have limited opportunities to practice their writing and receive meaningful individualized support from teachers, this additional feedback from GT helps students to revise and improve their writing (Tsai, 2020). As helpful as this may be for writing, Garcia and Pena (2011) shared that some students were skeptical about the ability of GT to actually help them learn the language, with concerns regarding overdependence on the technology. Students were also skeptical about just how good the GT translations were, especially among the beginner group (Garcia and Pena, 2011). Tsai (2020) addresses this issue, stating that students need to build up language skills well enough “to read and understand what is translated by Google Translate” (p. 16), especially considering GT still has limitations and students may be hesitant to rely on it too heavily due to grammar issues prevalent within earlier versions.

These studies (Bin Dahmash, 2020; Garcia & Pena, 2011; Tsai, 2020) help show the power of using GT both for learning and writing purposes, but also point to limitations. In doing so, they seem to concur with the sentiment expressed by Mundt and Groves (2016) that if “used carefully, and with imagination, the software can be used to aid the language learning process, not replace it” (p. 398). Put another way by Garcia and Pena (2011) who use the analogy of using a Global Positioning System (GPS): “one might note that while it certainly helps you reach your destination, it does not train you how to get from Point A to Point B autonomously” (p. 486).

What all of that taken into consideration, what if one’s main objective is not language learning but rather communication? To play back to the analogy, what if you are comfortable always using GPS to reach your destination? What possibilities are opened if mastery of a new language is no longer required to study in that language? Mundt and Groves (2016) suggest that as MT technology furthers in its development there may be potential for students to bypass the need to comprehensively learn a new language in order to study in that language, and that schools may need to consider whether language requirements are still necessary. Regardless of whether or not this becomes the case, schools will need to be clear in their guidelines for acceptable use, especially when it comes to cases of plagiarism. While it is an obvious violation to take work from another language and present a translated version as one’s own, there is a question of whether writing in one’s own language and presenting the GT version might also be considered as plagiarism, as “the work they are submitting is theirs, but could not be truly said to be theirs on totality” (Mundt & Groves, 2016, pg. 395).

Conclusion

So what is the future of language learning, and what role will MT systems like GT play? How important will language learning become as communication barriers continue to fall? Mundt and Groves (2016) believe that “GT clearly has an effective part to play in the future of transnational education, and can help students and staff cross linguistic boundaries more easily and faster” (p. 398). The extent to which that happens will undoubtedly depend on how advanced these systems become and how widespread their acceptance is. While it is difficult to see MT systems completely replace the need to learn new languages – or replace the need for professional translators for that matter (Läubli & Orrego-Carmona, 2017) – they are no doubt on their way to leaving a lasting impact on both language learning and interlingual communication.

References

Bin Dahmash, N. (2020). ‘I can’t live without Google Translate’: a close look at the use of Google Translate app by second language learners in Saudi Arabia. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume, 11. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no3.14

Läubli, S., & Orrego-Carmona, D. (2017). When Google Translate is better than some human colleagues, those people are no longer colleagues. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-147260

Garcia, I., & Pena, M. I. (2011). Machine translation-assisted language learning: writing for beginners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(5), 471-487. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2011.582687

Mundt, K., & Groves, M. (2016). A double-edged sword: the merits and the policy implications of Google Translate in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 387-401. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2016.1172248

Tsai, S. C. (2020). Chinese students’ perceptions of using Google Translate as a translingual CALL tool in EFL writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-23. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2020.1799412

Turovsky, B. (2016, April 28). Ten Years of Google Translate [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.blog.google/products/translate/ten-years-of-google-translate/

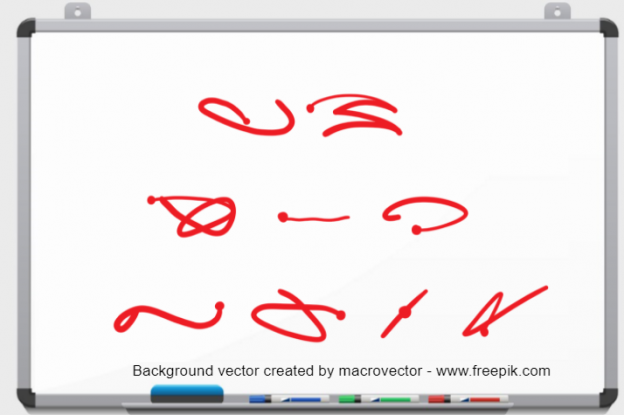

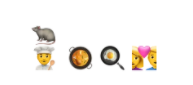

Lion + crown –> has to be Lion King

Lion + crown –> has to be Lion King “Small” + city, cornfields + aliens –> gotta be Smallville

“Small” + city, cornfields + aliens –> gotta be Smallville rat + chef –> As another classmate put it, there aren’t a lot of movies about rats and chefs…definitely Ratatouille.

rat + chef –> As another classmate put it, there aren’t a lot of movies about rats and chefs…definitely Ratatouille.