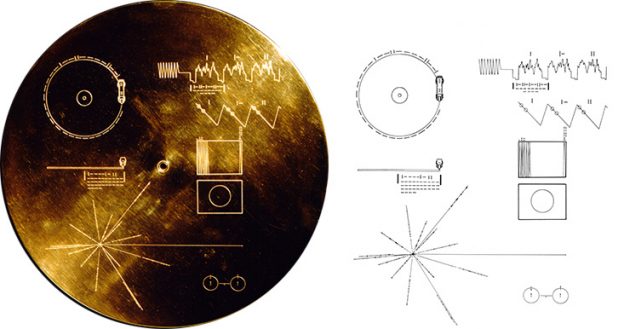

For this task, I was required to curate a set of 10 songs from the 27 included on the Voyager spacecraft’s Golden Record. Below you will find the full list of songs, with my selections indicated in red (alongside an *), along with a brief rationale for my choices:

- Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement, Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor. 4:40

- Java, court gamelan, “Kinds of Flowers,” recorded by Robert Brown. 4:43

- Senegal, percussion, recorded by Charles Duvelle. 2:08

- *Zaire, Pygmy girls’ initiation song, recorded by Colin Turnbull. 0:56

- Australia, Aborigine songs, “Morning Star” and “Devil Bird,” recorded by Sandra LeBrun Holmes. 1:26

- Mexico, “El Cascabel,” performed by Lorenzo Barcelata and the Mariachi México. 3:14

- *”Johnny B. Goode,” written and performed by Chuck Berry. 2:38

- New Guinea, men’s house song, recorded by Robert MacLennan. 1:20

- Japan, shakuhachi, “Tsuru No Sugomori” (“Crane’s Nest,”) performed by Goro Yamaguchi. 4:51

- Bach, “Gavotte en rondeaux” from the Partita No. 3 in E major for Violin, performed by Arthur Grumiaux. 2:55

- *Mozart, The Magic Flute, Queen of the Night aria, no. 14. Edda Moser, soprano. Bavarian State Opera, Munich, Wolfgang Sawallisch, conductor. 2:55

- *Georgian S.S.R., chorus, “Tchakrulo,” collected by Radio Moscow. 2:18

- Peru, panpipes and drum, collected by Casa de la Cultura, Lima. 0:52

- *”Melancholy Blues,” performed by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven. 3:05

- *Azerbaijan S.S.R., bagpipes, recorded by Radio Moscow. 2:30

- Stravinsky, Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance, Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Igor Stravinsky, conductor. 4:35

- Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Prelude and Fugue in C, No.1. Glenn Gould, piano. 4:48

- *Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, First Movement, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Otto Klemperer, conductor. 7:20

- Bulgaria, “Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin,” sung by Valya Balkanska. 4:59

- *Navajo Indians, Night Chant, recorded by Willard Rhodes. 0:57

- Holborne, Paueans, Galliards, Almains and Other Short Aeirs, “The Fairie Round,” performed by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. 1:17

- *Solomon Islands, panpipes, collected by the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Service. 1:12

- Peru, wedding song, recorded by John Cohen. 0:38

- China, ch’in, “Flowing Streams,” performed by Kuan P’ing-hu. 7:37

- *India, raga, “Jaat Kahan Ho,” sung by Surshri Kesar Bai Kerkar. 3:30

- “Dark Was the Night,” written and performed by Blind Willie Johnson. 3:15

- Beethoven, String Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Opus 130, Cavatina, performed by Budapest String Quartet. 6:37

(available from NASA, n.d.)

I chose these recordings based on a few criteria. First and foremost, I wanted recordings that were pleasant to the ear and showed impressive levels of talent, treating the record like a showcase of what humans are capable of (hence my selection of the Mozart piece with its impressive singing and my exclusion of Men’s House Song, which I found it be irritating). I also wanted to include examples of different languages, especially those in great contrast to each other (like with Johnny B Goode and Jaat Kahan Ho). It was important to include some non-Westernized music and their accompanying instrumentations, to help express the fact that there are many different cultures on earth, but in a small enough proportion to express that there is a shared experience central to a large population here on earth. I also wanted to express a sense of community – an important component to humanity – which is why I chose pieces with multiple instruments and/or singers, like in the case of Tchakrulo.

These selections were also informed by the idea that in preserving this record of humanity, we need to be careful not to present a monoculture representative only of the governing body involved (Brown University, 2017). I also placed an emphasis on attempting to provide as much variety as possible, which was part of the goal of the original curation of 27 pieces (Taylor, 2019). For that reason, I eliminated some songs, like the Peruvian panflutes, because of the similarities they shared with others (the panflutes from the Solomon Islands). Overall, my goal was to preserve as much of the original intent of the record as possible in a compressed format.

References

Brown University. (2017). Abby Smith Rumsey: “Digital Memory: What Can We Afford to Lose?”

NASA. (n.d.). Golden record/what’s on the record: music of earth. Jet propulsion laboratory – California institute of technology: voyager. https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/golden-record/whats-on-the-record/music/

Taylor, D. (Host). (2019). Voyager Golden Record [Audio podcast episode]. In Twenty Thousand Hertz. https://www.20k.org/episodes/voyagergoldenrecord