“Algorithms are nothing more than opinions embedded in code.”

(Cathy O’Neil in Talks at Google, 2016)

“A machine-learning algorithm can’t tell the difference between being morally good, neutral or unjust forms of bias, so that’s something humans have to be much more careful about.”

(Shannon Vallor in McRaney, 2018)

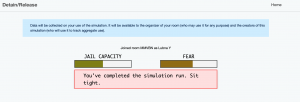

The Detain/Release simulation was a fascinating yet unsettling and disturbing task that revealed much about how flawed the judicial system seems to be.

While going through the simulation, I had many questions and needed more information on individual cases. For example, if the crime was theft, then of what exactly? What was the nature of the robbery? Not all offences are of the same rank, as the case of the 18-year-old who tried to ride a six-year-old’s bicycle to school, demonstrated in the McRaney (2018) podcast. How was the level of expected violence or crime of the defendants determined? What factors determined the recommendations of the prosecution? So much critical information related to the context of these human lives was missing. I also became more acutely aware of my own biases, releasing women (perhaps they were mothers?) and instinctively assuming they were ‘less dangerous’ than men.

Each click to Detain or Release was burdened by the idea that these decisions would have far-reaching effects on real human lives.

The process raised the question: Can machine code integrate human context and compassion critical to these decision-making processes? The answer is no, so these algorithms must be used cautiously, with wisdom and ethically-guided human supervision.

From the podcasts I listened to this week, much stood out. Now that algorithms are becoming pervasive in virtually every sphere of life, from banking, shopping, policing, and transportation to education etc., then Data Ethics – a super-critical domain today – must be prioritized. Transparency must be demanded.

“Before we start talking about machine morality, we have to think about human morality, that is, the morality of the people designing the machines..”

(Shannon Vallor in McRaney, 2018)

References:

McRaney, D. (Host). (2018, November 21). Machine Bias (rebroadcast) (no. 140). [Audio podcast episode]. In You Are Not so Smart. SoundCloud.

Talks at Google. (2016, November 2). Weapons of math destruction | Cathy O’Neil | Talks at Google. [Video]. YouTube.