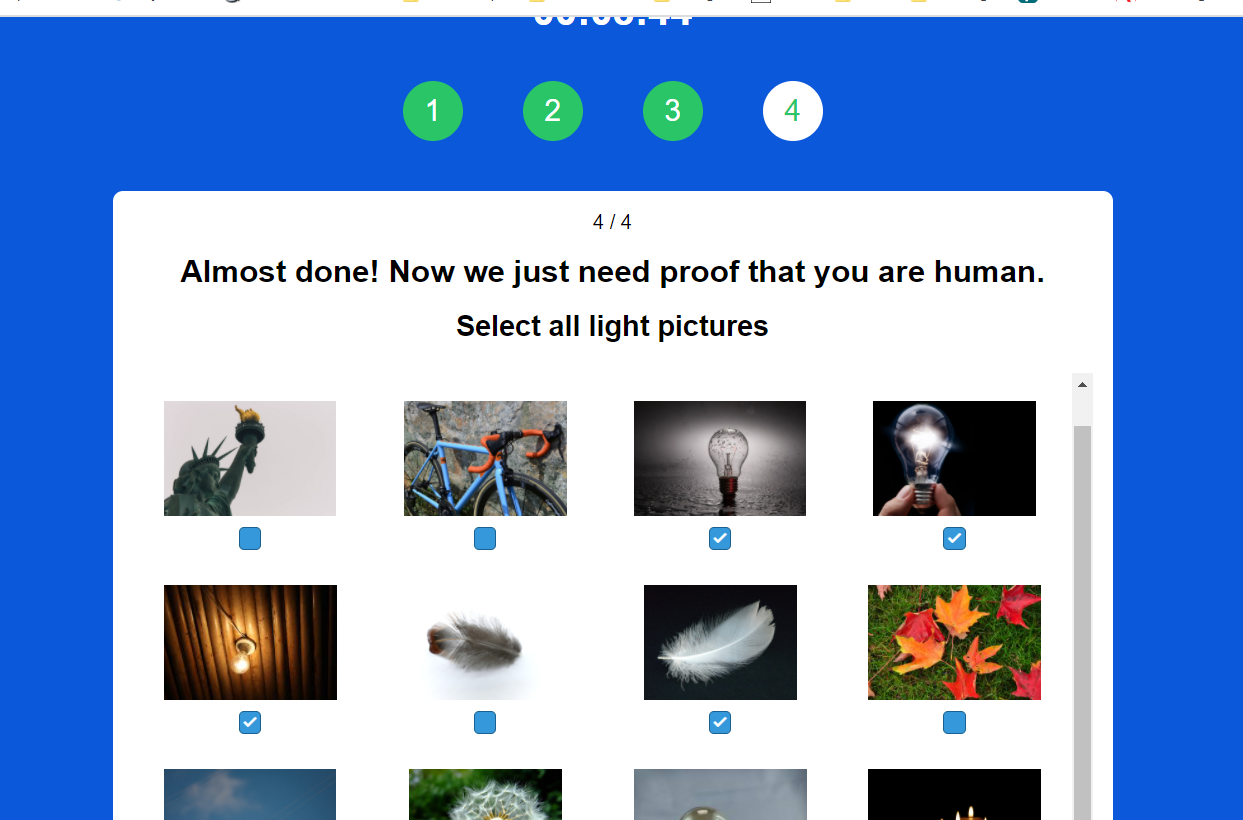

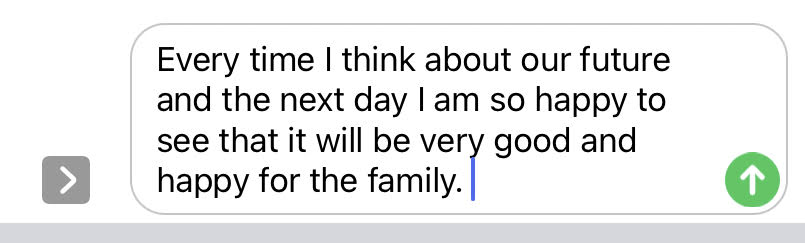

I decided to go with three prompts for this exercise and the results are as follows:

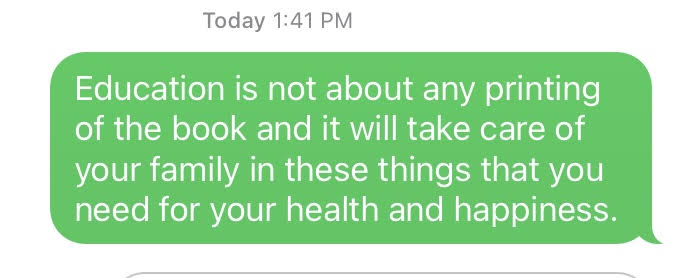

In both scenarios, even though the content sounds correct, the messaging is not what I had intended. For the first prompt “Education is not about…” I was hoping to write something based on the different learning theories, but the message I ended up with was more existential in nature. In the second message, ideally, I would have written something about the future of our society or humanity as a whole, but again due to the nature of the predictive text, I ended up with messaging that was too generic and limited to the personal context of my family.

I saw a lot of similarities in the predictive text suggestions that popped up no matter the prompt I used. For example, in the above scenarios, even though the prompts are different it is interesting to see how words like “happy or happiness” and “family” pop up despite the theme of the prompt. These are clearly based on the words and phrases that I have been using a lot in my general messages, and the predictive text algorithm clearly picks up and shows these words based on its probability.

Here’s another one that I tried!

Again, this is not something I would have consciously thought of or written if it had not been for the predictive text.

In all of the examples above, I feel the ‘voice’ sounds very stilted and not like my own. It either sounds too affected or overly prescriptive—and not reflective of what I really intended to communicate.

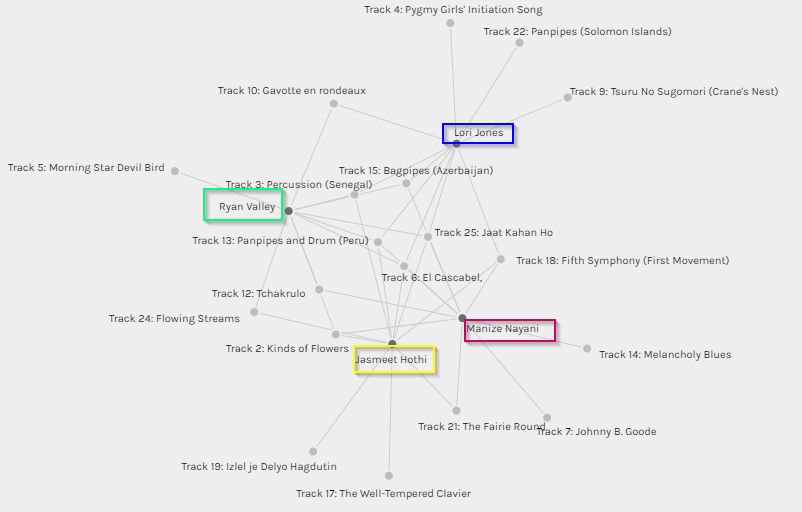

Regarding AI algorithms, I agree with Vallor (Santa Clara University, 2018) that these algorithms are good when it comes to automating routine, predictable tasks. But the minute we introduce real-world problems, or anything nuanced, these automations become an issue. This is evident in the predictive text microblogging exercise. I have used the automated predictive text feature in Gmail for writing every generic, standard responses and this feature has worked well. But the minute we try to talk about opinions, ideas or something complex and abstract, the predictive text feature falls severely short. Vallor further states that every AI is a mirror of our society. In such a scenario what is fed into the algorithm will determine its output. For example, words and phrases that I use frequently while messaging shows up in my predictive text while others do not. The output, therefore, is at times reflective and at other times distorted.

Another dark aspect of algorithms is the secrecy involved in sharing the data, something Dr. O’Neil addresses in her Google Talk (2016). During her talk, Dr. O’Neil mentions about personality tests that major companies deploy when hiring new staff. The scores and the result are never shared. I could connect to this example very well. In my personal experience, I once applied for a job in a Vancouver-based company. I completed five out of six rounds of interviews and tests. The sixth and final round was a personality test (similar to the Myers-Briggs but not quite). The options were vague, and I was not sure what was expected of me. After the sixth and final round I was rejected based on the outcome of the test. The analysis was not shared with me—the only thing I was told was that based on the results of the test I was not “a good fit”. Prior to the test, I had been interviewed by everyone from HR, to the reporting manager to the CEO and I passed all those interviews. But, when it came to a machine-based test, I failed. As Dr. O’Neil says, I was not even aware that I was being scored, and the unfairness of it all made me livid. It also made me wonder if the algorithm designed to provided ‘objective assessment’ in the test was fair and if it in fact superseded the subjective assessments of everyone who had interviewed me prior to the test.

Objective algorithms aren’t as objective or fair as one would like to believe. As Vallor says biases and prejudice are a part of our social data and one cannot separate the creators of these algorithms from the product. Plus, many of these algorithms have the potential for inflicting social harm. Dr. O’ Neil gives an example of algorithms that spread fake news that have the potential to affect a country’s democracy. The many examples provided by Dr. O’Neil validate the fact that the world of ungoverned algorithms has been going unmonitored for a very long time. It is time to take into account the political, ethical and social consequences of algorithms used for dubious, nefarious and at times downright illegal purposes.

References:

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy (First edition). New York: Crown.

O’Neil, C. (2017, July 16). How can we stop algorithms telling lies? The Observer. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/16/how-can-we-stop-algorithms-telling-lies (Links to an external site.)

Santa Clara University. (2018). Lessons from the AI Mirror Shannon Vallor.

The Age of the Algorithm. (n.d.). In 99 Percent Invisible. Retrieved from https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/the-age-of-the-algorithm/