Hypertext, the World Wide Web, and indirectly, the Internet, have played a part in remediating print in significant ways for over 20 years, and will continue to do so. This remediation has allowed writers and users of print and other forms of digital media to work towards accomplishing many long standing goals of sharing and collaboration, digital storage, and hypertextual linkages and dissemination in multiple forms. Regardless of this apparent advancement, one particular computer visionary, the man who coined the term “hypertext,” Theodore Nelson, believes that the World Wide Web has missed the mark; that it has replicated everything we could already accomplish with paper, books, catalogues and indexes, but has not truly captured the power and possibility of global computer networking. Theodore Nelson’s “Xanalogical structure” goes beyond creating an online digital library (which he equates with the Web), and proposes a system that aims to change established norms of hypertextual association that is transmitted via the Internet. Nelson’s vision aims to revolutionize how the Internet is used with regard to hypertextual print. To date this is a revolution that the computer world has not been ready to accept, though Nelson and his colleagues have been championing their cause for over forty years.

In his article, “Xanalogical structure, needed now more than ever: Parallel documents, deep links to content, deep versioning and deep re-use,” Theodore Nelson writes, “the World Wide Web was not what we were working toward, it was what we were trying to prevent. The Web displaced our principled model with something far more raw, chaotic and short-sighted. Its one-way breaking links glorified and fetishized as ‘websites’ those very hierarchical directories from which we sought to free users, and discarded the ideas of stable publishing, annotation, two-way connection and trackable change” (Nelson, 1999, Pg 3). To understand Nelson’s seemingly jaded perspective of the World Wide Web, we must step back to understand the short history of the Internet, as well as the tensions between philosophies as to how the Internet should be utilized with regard to print.

We commonly use the terms Internet and World Wide Web interchangeably, but we must be careful to make the distinction between the two. The Internet refers to the basic infrastructure that ties computer networks together around the world. In the early 1960’s the United States Department of Defence established the ARPANet — Advanced Research Project Agency Network. This was the first iteration of what was envisioned to be a national and someday international network of computers that would continue to function, even if some part of the network was destroyed in a nuclear attack or natural disaster. Over the course of the next 40 years, the ARPANet evolved to the Internet, utilized first by the military, but gradually by government and academic institutions to share and communicate electronic information. The Internet was opened to public and commercial users in the early 1990’s. At that time one of the pet names for the Internet was the “information superhighway.” The superhighway as a metaphor implies a main thoroughfare (the Internet) with a vast network of side roads (links to servers and individual computers around the world).

international network of computers that would continue to function, even if some part of the network was destroyed in a nuclear attack or natural disaster. Over the course of the next 40 years, the ARPANet evolved to the Internet, utilized first by the military, but gradually by government and academic institutions to share and communicate electronic information. The Internet was opened to public and commercial users in the early 1990’s. At that time one of the pet names for the Internet was the “information superhighway.” The superhighway as a metaphor implies a main thoroughfare (the Internet) with a vast network of side roads (links to servers and individual computers around the world).

Like any highway, the vehicles driven on the road are determined by the utility, preference, availability, cost, marketing, design, regulation and ultimately, choice of the users. A number of institutions, corporations and individuals recognized the potential of the Internet and began creating these vehicles. Among them Theodore Nelson proposed the Xanadu system (beginning in the early 1960’s), and Tim Berners-Lee and his collaborator’s developed the World Wide Web in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. By the mid 1990’s the computer world, and the world in general, had chosen to “drive” the World Wide Web on the Internet instead of the Xanadu system, though the latter had been in formation for almost thirty years previous to the conception of the Web. Why the choice of a recent upstart versus one of the pioneering systems of hypertext and hyperlinks?

I think the answer lies in the way people generally take up new technology. We tend to assimilate the technology vehicle that makes us more efficient in our current ways of knowing and doing, as opposed to those technologies that require a significant shift in our thought processes and product. We tend to try out technology that is affordable and prolific enough that we can own it ourselves, and find the help and support required to learn and use it. The World Wide Web served these ends; the Xanadu system did (does) not.

The World Wide Web connects documents, videos, sound files and images together utilizing hyperlinks and URL’s (Uniform Resource Locators), and navigates to these using specialized software called Web Browsers. Writing in 2001, Bolter makes a case for the World Wide Web having become “the great book,” a massive encyclopaedia or library of indexed information. Bolter writes, “the World Wide Web considered as an encyclopaedia is an utterly eclectic collection of texts and images” (Bolter, 2001, pg 90), and in terms the Web having become a metaphoric library, Bolter alludes to many individual library collections finding their way onto the Web in order to further the greater goal of a universal library (Bolter, 2001, pg 94).

The World Wide Web was computer technology’s answer to collecting and collating a world of text, images and digital media and making them widely accessible. On the Web, URL’s essentially replaced library call numbers, while portal websites became analogous to shelves full of books on all topics and search engines became the card catalogue. When we navigate the web we are directed to, or choose to travel to, an author or visual designer’s writing space, but it is up to us to glean and sort the information that is present, much like we find our ways to books in a library using indexes and database searches, and pick and choose what we want from them. And, like a library, web links and pages can we lost and discarded as easily as books are weeded from the shelves. While Nelson views this arrangement as “raw, chaotic and short-sighted,” the simplicity of navigation to web pages and various forms of digital media and the ease of uploading and downloading content were relatively easy concepts for people to grasp, manipulate, and use; hence the ease and rapidity of uptake for this technology.

The World Wide Web was computer technology’s answer to collecting and collating a world of text, images and digital media and making them widely accessible. On the Web, URL’s essentially replaced library call numbers, while portal websites became analogous to shelves full of books on all topics and search engines became the card catalogue. When we navigate the web we are directed to, or choose to travel to, an author or visual designer’s writing space, but it is up to us to glean and sort the information that is present, much like we find our ways to books in a library using indexes and database searches, and pick and choose what we want from them. And, like a library, web links and pages can we lost and discarded as easily as books are weeded from the shelves. While Nelson views this arrangement as “raw, chaotic and short-sighted,” the simplicity of navigation to web pages and various forms of digital media and the ease of uploading and downloading content were relatively easy concepts for people to grasp, manipulate, and use; hence the ease and rapidity of uptake for this technology.

Xanadu is not as easy for all computer users to grasp and apply. Nelson’s Xanalogical system demands a shift in thinking about how writing, text and information in general would and should be shared and associated via the Internet, both technically and with respect to attribution to the authors and creators (copyright). Xanadu was and is a difficult concept to explain, given there are limited working models for people to try and assist in its development and implementation. Unlike the Web, which in a few short years was packaged with personal computers and used widely by a wide cross section of users (including both open sources program developers and major computer companies), Nelson and his colleagues maintained strict creative control on the Xanadu system and the technology industry passed them by, creating a vacuum of working prototypes and access to the core technology which would allow the system to evolve. As a result, Xanalogical structure languishes in obscurity having never made it to the mainstream, much to Nelson’s dismay given his perspective on the limitations of the Web.

Nelson disparages the Web as nothing more than a disorganized digital library, that lacks the ability to fully access and arrange it contents. Nelson sees this as a missed opportunity as text and digital media is still being trapped in the old structures of “hierarchical directories,” in files, and outdated and forgotten web pages. He scoffs at the use of formats such as the “Portable Document Format (PDF),” as a way of preserving text, given its fixity, which works against querying and citing specific information. Nelson’s Xanalogical structure calls for the storage and protection of all versions of all hyper textual documents in fixed locations; the ability to work with and link parallel documents (documents that are based on or derived from each other); the ability to utilize methods of “deep linking” to an array of content, not limited by any artificial indexes or topical categories; the ability to establish “deep versioning” to preserve all iterations of the ev olution of a document, so that the past is preserved while the current insights and understanding of topics is presented; and the function of “deep re-use,” where all versions are available for inquiry and reuse, as opposed to only the most recent version.

olution of a document, so that the past is preserved while the current insights and understanding of topics is presented; and the function of “deep re-use,” where all versions are available for inquiry and reuse, as opposed to only the most recent version.

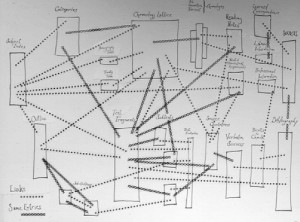

Nelson’s Xanadu project calls for a much more integrated arrangement of elements on the computer screen, whereby associative links between ideas and works are central to the concept. These links are bi-directional, and information is not lost when links are severed (in contrast, for instance, with lost information on the Web when websites are shut down). Nelson’s Xanological structure goes beyond the straight pathways and linear connections of the World Wide Web. To stretch the methaphor of the web to include Xanalogical structure, Xanadu could have an infinite number of webs, layered on each other, with cross connections at any point between the layers of webs. At the base layer of the webs is the permanently stored and shared data. A user or contributor on this system would be able to see all related topics and information for almost any strand of text or thought, linking deep down to the base (the primary documents or other types of data), or linking to any of the data that is stored in outer layers. In the following video, Theodore Nelson himself explains Xanological space (Nelson, 2008, September 6): T. Nelson explains and demonstrates Xanadu .

If it were to be realized, I believe Xanadu would go beyond remediating text to revolutionizing how text is created and shared. To be truly revolutionary, there must be a drastic and far-reaching change in ways of thinking and behaving. The World Wide Web and Xanadu represent a divide between technology being a tool to more efficiently do what we have always done, and a technology that radically changes what we do. In agriculture, for instance, farm machinery allows traditional methods to be done more efficiently, whereas genetically modified food offers methods that fully revolutionize the production of food. Do we want or dare choose the latter? What are the implications? When we focus on writing, we see a progression of technologies that have lead to increasing efficiencies – papyrus, quill & ink, scrolls, codex, manuscripts, paper, the first printing press, moveable type-set, steam presses, typewriters, word processors, the World Wide Web. These and many more technologies have added efficiency and proficiency to the act and art of writing, but were they truly revolutionary? In method of production, yes. In the fundamental act, not as much.

The Xanadu system’s impact on writing and print would be revolutionary. It could result in the melding of the world’s collective thought, layer upon layer, so that all creative work would eventually be interconnected with all other work. Why, then, hasn’t it caught on? Likely because it is not truly what we want, or at very least, are ready to accept at this point in history.

Writing has had a dualistic role in human thought throughout history. On the one hand it is meant to bring together the wisdom and knowledge of communal thought so that it can be shared in common. On the other hand, it is intensely individual, allowing for lone writers to create fully personal and intensely unique creations that define them as thinkers and philosophers. While writing is being remediated in many ways by technology, the underpinnings of the act of writing are still individual, and are still valued for being so. Xanadu appears to promote writing as a fully integrated and communal act, whereby one writer’s thoughts can be linked with another’s, and with the thoughts and understandings of every person that gradually becomes absorbed by the technology. There is a certain discomfort that comes with this loss of personal control — control handed over to the machine — which may very well contribute to the World Wide Web being retained as the Internet’s hypertextual vehicle of choice for the near future, regardless of its limitations and imperfections. However, Xanadu does offer many benefits around permanence of information and possibilities for digital authors to be recognized and compensated for their contributions that the current iteration of the Web cannot. If Xanalogical structure takes hold in software tools such as “token_word (Rohrer, J., 2000)” or “XanaWord (Di Iorio, A. & Vitali, F., 2003),” and people come to accept their loss of autonomy in favour of the benefits of rich collaboration and melding of print; or if Xanadu finds its place in the FreeNet world where more people can tinker with it and realize its power and potential, maybe then the computer world and the world at large will allow another revolution of print to come to pass.

Writing has had a dualistic role in human thought throughout history. On the one hand it is meant to bring together the wisdom and knowledge of communal thought so that it can be shared in common. On the other hand, it is intensely individual, allowing for lone writers to create fully personal and intensely unique creations that define them as thinkers and philosophers. While writing is being remediated in many ways by technology, the underpinnings of the act of writing are still individual, and are still valued for being so. Xanadu appears to promote writing as a fully integrated and communal act, whereby one writer’s thoughts can be linked with another’s, and with the thoughts and understandings of every person that gradually becomes absorbed by the technology. There is a certain discomfort that comes with this loss of personal control — control handed over to the machine — which may very well contribute to the World Wide Web being retained as the Internet’s hypertextual vehicle of choice for the near future, regardless of its limitations and imperfections. However, Xanadu does offer many benefits around permanence of information and possibilities for digital authors to be recognized and compensated for their contributions that the current iteration of the Web cannot. If Xanalogical structure takes hold in software tools such as “token_word (Rohrer, J., 2000)” or “XanaWord (Di Iorio, A. & Vitali, F., 2003),” and people come to accept their loss of autonomy in favour of the benefits of rich collaboration and melding of print; or if Xanadu finds its place in the FreeNet world where more people can tinker with it and realize its power and potential, maybe then the computer world and the world at large will allow another revolution of print to come to pass.

Gordon Higginson, ETEC540 Major Project, Fall 2010

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Di Iorio, A. & Vitali, F. (2003). A Xanalogical collaborative editing model. University of Bologna (Italy). Available: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.105.7423

Nelson, T. (1999). “Xanalogical structure, needed now more than ever: Parallel documents, deep links to content, deep versioning and deep re-use.” Available: http://www.cs.brown.edu/memex/ACM_HypertextTestbed/papers/60.html

Nelson, T (2008, September 6). Ted Nelson demonstrates Xanadu Space. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=En_2T7KH6RA. Citation in text: (Nelson, 2008, September 6)

Nelson, T. (2010, October 23). Ted Nelson’s Homepage. Retrieved from http://ted.hyperland.com/ . Citation in text: (Nelson, 2010)

Rohrer, J. (2000) token_word: A Xanalogical Transclusion and Micropayment Method. University of California Santa Cruz. Dept. of Computer Science. Available: http://hypertext.sourceforge.net/token_word/token_word.pdf

Backgrounding information about the Internet and World Wide Web, retrieved November 28, 2010 from:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet#History

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_superhighway

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARPANET

Revolution definition, retrieved November 28, 2010 from: http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=revolution

Image of Xanadu Space retrieved November 30, 2010 from: http://www.futureofthebook.org/blog/archives/2007/10/ted_nelsons_still_on_the_job.html

Image of Internet Cloud retrieved November 30, 2010 from: http://www.unc.edu/~unclng/Internet_History.htm

Iamge of Xanadu hyperlink diagram retrieved November 30, 2010 from: http://www.xanadu.com.au/ted/zigzag/xybrap.html

Image of Internet cartoon retrieved November 30, 2010 from: http://free-mail.co.za/new/index.php/a/2006/10/17/we_deleted_the_internet_google_cartoon

Image of writing and computer retrieved November 30, 2010 from: www.ccp.edu