As an avid read and writer of fiction, what I found particularly thought provoking in the readings of the third module was the exploration of the effect of writing and subsequently print on style, plot structure, and characterization in narrative. Ong (1982) aptly describes how narrative is the “elemental way” in which to process and express human experience (p. 137).

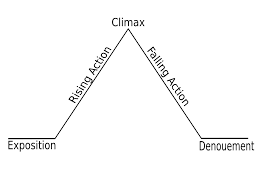

Narrative is of particular importance to oral cultures as a method to store and communicate knowledge in a largely durable format. Ong again emphasizes the need for noetic structures in oral cultures to assist with recall and memory, relying on “remembered traditional formulaic and stanzaic patterns” (p.142). Instead of narratives designed with a climactic linear plot, such as those that utilize Freytag’s Pyramid, oral narratives instead hasten into the action. Ong argues that this was the “original, natural, inevitable way to proceed for an oral poet approaching a lengthy narrative” (p. 141) I have a hard time accepting this structure as wholly natural and inevitable, while excluding consideration for thoughtful developments to assist a medium that did not have the benefits of writing.

Ong uses the Illiad and the Odyssey as examples, pointing to their episodic narrative structure that suggest “boxes within boxes created by thematic recurrences” (p. 141). Modern narratives do not always follow a linear, formulaic plot structure, however, as the medium continues to evolve and authors experiment in narrative structure. Some are even structured in ways that share traits with the oral narrative structure. For example, Steven Erikson’s series Malazan Book of the Fallen drops readers into the middle of a long-standing conflict with opening chapters that are climactic in nature, leaving it up to the reader to piece together the unwritten narrative that has come previously. The series continues by spanning multiple continents, cultures, and millennia in an episodic, non-linear fashion that eventually connects together. Each entry in the series, however, displays clear climactic sequences, but are depicted by jumping between multiple characters’ viewpoints.

The oral poet and modern author in a literate society are clearly two distinct roles related to story telling, as Ong contends that the oral epic was not related to creative imagination as we typically attribute to written narrative. Ong argues that an absence of a linear plot in oral narrative is not a conscious decision, but rather a concept that is not available without writing, and goes so far as to state it is not conceivable in oral culture (p.140). I find this assertion problematic as Ong again creates a strong dichotomy between the ways in which oral and literate cultures are capable of thinking. Oral and written narratives are ultimately distinct mediums of story telling that are influenced and limited by available technologies. I certainly cannot imagine distinguishing what I know of plotting and writing fiction from writing.

Ong’s characteristics of the written narrative structure reflect his arguments for the effect of writing on the human thought process. The characteristics include the decontextualization of the reader and writer by distancing them, the possibility of revisions, and the written text as a self-contained and permanent unit, all of which influence the development of a tighter plot structure. Ong argues that for the author, this lead to increased originality and creativity. While this may be true that compared to oral poets authors are not re-telling stories, they tend to also be avid readers and are thus almost always influenced by other literary works, while attempting to avoid clichés and stereotypical character designs. The widespread use of print further cemented the linear plot structure, creating a consistent standardized body of text that promoted private and individual reading, altering the relationship of reader and the text, and shifting focus from the producer to the consumer (p.120). Concepts such as the tone, style, and viewpoint of the written narrative would develop, and considerations of the physical layout of the text as well as narrative rhythm (when to give readers natural break points or hook them to continue to continue reading) would need to be considered.

The ability of an author to plan, edit, and revise a written text allows for meticulous plot structuring. Modern epic fantasy series such as George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire certainly would not be possible without the aid of writing, not only for the sheer length of the narrative, but for the meticulous research, planning, outlining and world building required as the narrative shifts between numerous character viewpoints; although, interestingly, George R. R. Martin claims to be largely a “discover” writer. The advent of the word processor made the planning and revision process even easier as writers could instantly erase or move text, and digitally search throughout an entire document. Texts such as Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange or the works of Tolkien in which fictional slang or entire languages are invented no doubt would not be possible without the ability to document and store information in a written format.

Modern authors such as Vladimir Nabokov have toyed with the idea that written text is a distinct self-contained unit that does not and cannot represent reality. In Lolita Nabokov carefully constructed a novel that blends a fully realized world that exists in a fictionalized plane of reality within an unreliable narrator’s subjective fantasy. Written narratives may be meticulously constructed and in this sense unnatural, but so too was the oral epic, only in a different format.

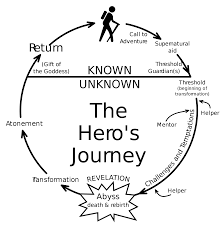

Ong briefly acknowledges there are numerous other societal factors that have influenced the evolution of narrative structure throughout time, but still has a deterministic tone when relating writing’s influence on ways of thinking and thus on constructing narratives. The evolution of narrative plot structure up to the modern novel has been a slow process. Ong seems to inadvertently attribute Freytag’s Pyramid as a universal narrative design during the early introduction of drama and the modern print novel, but does briefly mention the “deplotted story of the late-print or electronic age” (p.150). The pyramid plot structure, now more often structured as a check mark with varying “stages” or number of story points, is still taught in introductory creative writing courses. Other plot structures, such as the “hero’s journey,” popularized more recently by Tolkien, have gained popularity and fallen out of favor throughout time as well. Although a climactic plot point is a fairly standard plot device, many authors tend to avoid plotting that is too formulaic, instead favoring experimentation of form to avoid reader fatigue and predictability. However, with the development of television and cinema we have seen a new, albeit familiar, standardized narrative structure, that of the “Hollywood formula,” evident not just in screen writing, but in the novel as well, particularly those that are highly commercialized.

Bolter (2001) has a more reasonable argument regarding the effect of writing on the literate mind and narrative structure, contending that there is a more reciprocal relationship between technology and human thought and practice. Bolter writes, “Linear writing is appropriate to print technology both because the printed page readily accommodates linear text and because our culture expects that printed prose should be linear” (p. 17). If the development of print and the novel lead to a consumer focus, then surely the evolving interests of the consumer has influenced narrative structure and genre, as certain structures and genres come in and out of fashion. Unfortunately, this has lead us to such literary works as Twilight and Fifty Shades of Grey.

The technology of writing and later print allowed for and influenced developments of narrative structure and characterization, but these developments were also influenced by numerous societal factors. The written text allowed for the development of linear plotting and complex characters maybe not possible in the oral narrative in which theory and practice evolved over time. I think it is important, however, to think of oral and written narratives as two unique mediums and art forms, much like the written narrative and cinema, and not place limitations on each based solely on the available technologies acting upon the human psyche.

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Burgess, Anthony. (1962). A clockwork orange. London: Penguin Books.

Nabokov, Vladimir. (1955). Lolita. New York: Random House.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.