I’m always wary when a chapter claims to base much of its analysis in a domain conventionally perceived as an extension of “Marxist or neo-Marxist examinations” and then attempts to veil the terminology with different nomenclature. The red flag, for me, occurs when these examinations are coupled with mentions of French postmodern thinkers like Jacques Derrida.

I think Jacques Derrida was an exceptionally brilliant thinker and there are many things he put forth that I agree with. For example, one of Derrida’s central claims was that of deconstruction; the idea that there are a near infinite number of ways to interpret an event or a text. I believe this to be technically true, however, when you begin to couple this type of thinking with the aforementioned neo-Marxist viewpoints, we begin to run into a potentially dangerous paradigm depending on how far you push this ideology. Further, despite the agreement that there may be a near infinite number of ways to interpret an event or text, there remains only an incredibly small percentage of those interpretations that can be considered tenable by any reasonable standard.

Having studied Walter Ong in years past, it was refreshing to review his distinction between primary and secondary orality and contrast it with the theories of Havelock who insists it’s essentially impossible for a literate mind to conceptualize what primary orality would even look like. I can’t help but wonder if any members of primary orality would be able to function in or comprehend the secondary or even tertiary evolutions (I would consider this the digital age we currently find ourselves in) of language we are experiencing today. Regardless, all these thinkers share the same central tenant – that writing is a technology invented by human beings and that technology has evolved over time. But why? And what relationship does it have in shaping our cultural makeup?

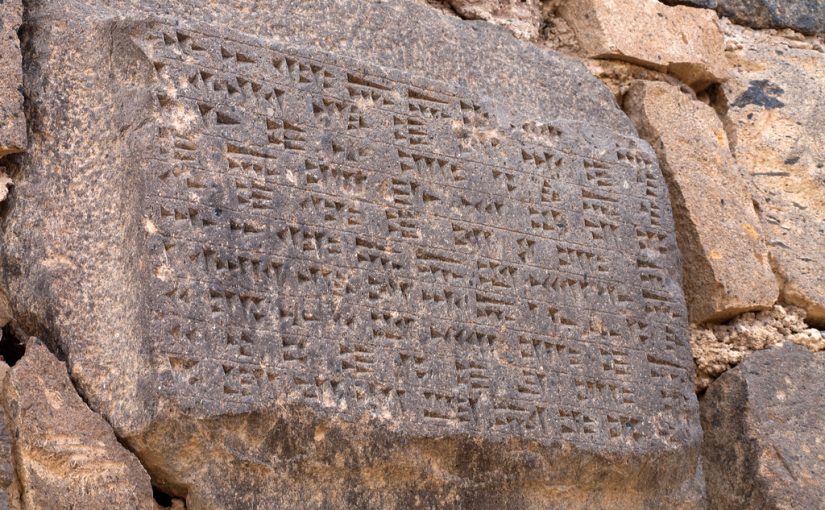

Gnanadesikan’s article was the most impactful to me when dealing with this concept – Outside of its readability, it formulated the most convincing argument: despite the Platonic arguments of a binary relationship between speech and text, writing has a foundation in memory. Writing has a contractual beginning; one that was invented out of necessity to track, record, and mark information. This information has its roots in both economic and psychological purposes: Early forms of writing reflect records of information pertaining to taxes, trade agreements, but also extends to the grand narratives and mythologies of societies. Weaving together the Haas article, this is essentially what the West was built upon: the importance of having the spoken word written, as if that made it unbreakable. That word exists solely in the ether until it is written down and made physical.

Ong’s line of thought supports this – Before material information was present, all one could do was ‘recall’. He also claims that writing was invented in urban centres, thereby lending to the theory that writing is a central cornerstone in the flourishing of any civilization. Perhaps one of the most fascinating ideas developed by Ong is his characterization of new media:

“A new media never wipes out the old, it always reinforces it, but it changes it, so that it no longer does what it used to do the same way. You must know the new medium or you can’t use the old…“

When it comes to our newest form of media (digital media) I am compelled to think about all the changes it has brought and the changes that it has brought about. I stand by a previous claim about one of the more undervalued and revolutionary changes brought about by our new digital media: the hypertext. The hypertext has created fundamental changes when it comes to the storage, retrieval, and obtaining of information within digital realms. It transcends the existing barriers of physical texts and has transformed the internet itself into something like a disentangled book. At the most superficial level, the layering of digital information through the transcribing of data nodes has, by and large, increased the speed with which digital text users can access information. I wonder what other deep cultural changes this may have produced…

Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2011).“The First IT Revolution.” In The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the internet (Vol. 25). John Wiley & Sons (pp. 1-10).

Haas, C. (2013). “The Technology Question.” In Writing technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy Routledge. (pp. 3-23).

Ong, Walter, J. Taylor & Francis eBooks – CRKN, & CRKN MiL Collection. (2002). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Chapter 1 .New York; London: Routledge.