In our third week of ETEC540, we were tasked with relating an unscripted narrative into a chosen voice-to-text application, record the outcome, and analyze the degree to which English language conventions were deviated from. We were also instructed to observe what we believed to be ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ within the recorded text, and make an intentional link between the distinctions of oral and written storytelling.

I had fun with this experiment, and employed the voice-to-text program (https://speechnotes.co/) in a number of scenarios. I recorded myself narrating a portion of my lesson on The Alchemist to my class, I documented a phone conversation between myself and my partner to observe the degree of accuracy voice-to-text could produce by hearing speech through a separate technology, and I chronicled a conversation I had with a colleague at work.

There are some surface level connections between myself and many of my colleagues: Manize and I both used SpeechNotes, while comparatively, Olga utilized the Dictation tool on her Windows computer. We all recognized that literally mentioning the punctuation mark to the program would have drastically changed the meaning of the text, but conceded that this should not be a necessary step. Regardless, one of the most commonly agreed upon ‘mistakes’ in the voice-to-text scenario was the absence of grammatical and structural conventions. These typographical signs manifest themselves most frequently in basic punctuation like commas, periods, and capitalization and the lack of these proper morphological protocols give credence to the assertion that voice-to-text technology does not yet quite adequately have the ability to discern those written symbolic gestures from oral speech. Both Olga Kanapelka and Manize Nayani are colleagues that reflected on this idea, and went on to suggest that there were also many structural components of writing that were nonexistent within the text. For example, one of the more difficult aspects in comprehending the voice-to-text block of writing is that ideas are not organized or structured through the use of sentences or paragraphs. Through comparing our voice-to-text products, it’s clear that no matter what voice-to-text tool is used, the scarcity of grammatical and structural concordances remain. The lack of these literary principles, coupled with the inability to punctuate, make it increasingly difficult to effectively interpret the true narrative essence of the text.

There are, however, some deeper connections between myself, Olga, and Manize: our voice-to-text body of writing was created through the influence of an accent. Olga, Manize, and myself reflected on the adequacy of spelling and level comprehension within our bodies of text. We all seemed to touch on the degree to which accents played a role in the formation of meaning-making within speech-to-text outputs; both in the sense of the program understanding what has been spoken, and in the sense of ensuring the written product was intelligible.

Manize revealed that English is her second language as she moved to Vancouver from Mumbai, India some years ago. She seems to imply that many of the words picked up incorrectly were a result of her accent. She also posits that she believes having a story scripted would have permitted her to speak with more clarity and the number of spelling mistakes would have decreased. Similarly, Olga discloses that English is also her second language and specifies that English vowels are most difficult for her to pronounce. Similarly, when prompted to think about the difference of the written output if it were influenced by a script, Olga seemed to suggest the same idea as Manize: that the script would have aided in clarity and cohesion, ultimately resulting in a more readable text.

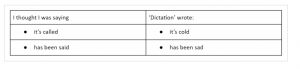

Olga provides a clear example of how her accent directly affects the voice-to-text transcription program:

Olga was clear and intentional about how her accent could be misconstrued by the program. This was interesting to me, and indicated that voice-to-text technologies do not listen for context, they simply listen for sound. In other words, it listens, but it does not hear. On a separate but related note, I find it ironic that many of our chosen A.I voices (think GPS’s) can be manipulated to reflect a plethora of accented voices from across the world, yet struggle in deciphering accented spoken words. I wonder if the Australian GPS voice could effectively transcribe a true Australian accent for example.

Although English is my primary language, and I do not speak with an accent (although some here in Vancouver think I speak with an Ontario or ‘Toronto’ accent), I recorded a conversation with a colleague of mine who speaks with a very thick English accent. The results were astounding in comparison to my original spoken narrative. Perhaps it was the fact that this was a conversation; that more than one person was talking, or that my colleague’s accent made it difficult for the voice-to-text program to discern was was truly being said, but the entirety of the text is blatantly incoherent. It was a stark contrast to my two colleagues who, despite scattered errors in spelling and coherence, theirs was predominantly intelligible.

Ultimately, it seems as if we all agree there is a certain level of flexibility when it comes to oral storytelling. Despite the mnemonic element required in reiterating a narrative, the story does not necessarily follow a strict sequential structure. Verbal strategies like emphasis, energy, intonation, volume, and pace can all contribute to the (in)effectiveness of orality while in written narratives, these elements are much more limited. I would even go as far as saying the accented influence of a narrative bestows it with more character and authenticity. Perhaps these elements appear, but in a fundamentally distinct way (punctuation?). Moreover, there is a certain level of grammatical forgiveness in orality – audiences are much more lenient when it comes to the variety of ‘mistakes’. There is no deleting an oral story, but there can be correction.

Bauman, R., & Sherzer, J. (Eds.). (1989). Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking (2nd ed., Studies in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611810

Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2011).“The First IT Revolution.” In The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the internet. (Vol. 25). John Wiley & Sons (pp. 1-10).