I think it first serves us well to understand that algorithms are rooted in nature and within collective organisms, not within computers. It is unwise to understand algorithms as explicitly applied to computers, robots, or codes.

In its most basic form, an algorithm is simply a methodical set of steps that can be utilized to make calculations, realize a determination and/or choose decisions. More often than not, the perception is that algorithms are contextualized as codes embedded within the language or computers, but similar to McRaney’s assertion that prejudices are inherent within the way human beings make decisions, so too are algorithms intrinsic in the way we survive. At a neuroscientific level, what are emotions other than biochemical algorithms vital for the survival of all mammals? What is the process of photosynthesis other than mother nature’s algorithm for plant growth? Artificial Intelligence (A.I) simply mimics the most basic human configuration for decision making; all we have done is project our humanistic operations and behaviours into an artificial medium (Vallor, 2018).

With that said, I do believe we are currently sitting at a significant crossroads where we may be implementing technologies, specifically with respect to A.I, without recognizing the potential unintended consequences. Cathay O’Neil speaks about this concept at length and focuses her line of thought on judiciary matters, educational administration, and fundamental hiring practices. It seems only recently have we begun to recognize the implicit biases A.I technologies seemed to have inherited from their creators. Examples are endless: Legal analysts are rapidly being replaced by A.I, meaning that successful prosecutions or defences can rely almost wholly on precedents reconfigured as algorithms, and even predict future criminals based on certain human factors (see: Machine Bias Against African Americans). The job market increasingly relies on A.I tech to filter CV’s. Most human eyes will never fall upon a prospective employee’s resume again, effectively placing people’s livelihoods at the mercy of machines (see: Amazons AI hiring tool biased against women). Ultimately, these algorithms are caricatures of our own human imprints.

So when I think about the predictive text feature on my phone, and the created sentences generated by the prompts, I can’t help but feel that there is a piece of me in there somewhere. I have a Google Pixel phone, and used the predictive text feature in the messaging app. I find that the feature is excellent when I need to correct a spelling error, or suggest the next potential word while I am in the process of texting, but I did not find it helpful at all for this exercise. When given the freedom to produce its own sentences, it failed to construct anything coherent. For the record, I do not think any of these predictive text iterations sound remotely like me.

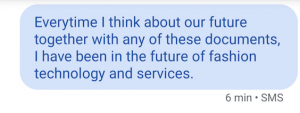

My instincts tell me that the predictive text feature analyzes the words and phrases used the most within my texting app and generates the next most likely option. I found small successes when formulating two to three word phrases, but outside of that, there was much left to imagination. Take this example here: “Everytime I think about our future together with any of these documents, I have been in the future of fashion technology and services” . ‘Future’ appears twice in this sentence, and I can at least understand it’s relativity to ‘technology’ and ‘services’ for example. Alternatively, I haven’t the slightest clue where it got ‘fashion’ from.

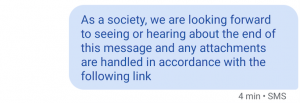

This second example makes a little more grammatical sense, and is slightly more eloquent in its delivery, but the fact remains that I simply do not text like this. There is a high degree of formality in this rendering, as if I was speaking to a workplace superior. I found it interesting that both examples incorporated elements of documents and attachments. Perhaps a reflection that I’m working too much… Moreover, these predictive texts are fairly good at sensing when there truly is a link available (often when a link is sent, there will be a mini-previous provided), but of course, there was no link sent.

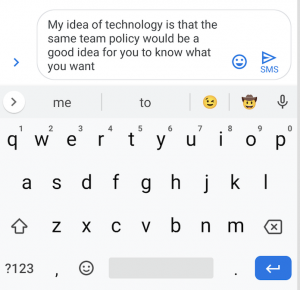

Perhaps the most interesting example to me was the following predictive text that was typed but not sent. I wanted to provide an alternative perspective and make available a sort of ‘behind the scenes’ image to illustrate what predictive aspects were offered to me:

The most striking feature in this image is the predictive emoji being offered: the smiley with a cowboy hat. Not only do I question the emoji’s particular relevance within this predictive body of text, but I can confidently say, without a shadow of a doubt in my mind, that I have never once used the cowboy hat emoji in any context whatsoever. I am dumbfounded by what algorithm decided to offer me the cowboy hat emoji as an option here.

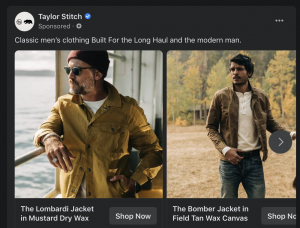

I struggled to discern these types of predictive patterns in academic articles, novels, or anything of the like (perhaps I’m just being naive in that sense), however, I did seem to recognize similarly structured sentences in social media infrastructure, and online ads. For example:

Perusing Facebook permitted me to acknowledge some potential predictive text, within a specifically targeted predictive advertisement. I don’t spend that much time on Facebook, truthfully, but I know that this being a sponsored ad, I was obviously a target of a number of specific algorithms designed to place this ad in front of me. The text in the ad strikes me also as predictive: “Classic men’s clothing Built For the Long Haul and the modern man.” Something about it just doesn’t seem human – Why are there capitals in the middle of the sentence? Why does the modern man portion seem like it’s just been tacked on at the end? Perhaps this is where my predictive text got fashion from…

Conversely, I am aware of automated journalism as a concept gaining much traction. I think it’s important to echo one of O’Neil’s sentiments about the rise of A.I powered machines; that we shouldn’t attempt to employ A.I as a means to eliminate human enterprise, but rather as a tool to empower it. In reading the aforementioned A.I generated news column, I do find it to be extremely ‘bare-bones’ in the sense that it is only relaying specific facts, rather than injecting a creative or original tone into the story. Perhaps this is a mode reserved more effectively for sports or finance news stories.

One of the ethical dilemmas we tend to find in this particular arena is simply: what is truth? We are inclined to think that journalists are held to high standards and are bound to their journalistic commitment to spreading what is true. But it’s no secret that in recent years, we’ve seen a decline in ethical journalism and the overall journalistic standards in the industry. Is this a journalist’s fault? Can we blame A.I for this? It’s a difficult area, but they both seem to have a hand in the rise of fake news, and the fall of ethics within journalistic standards.

McRaney, D. (n.d.). Machine Bias (rebroadcast). In You Are Not so Smart. Retrieved from https://soundcloud.com/youarenotsosmart/140-machine-bias-rebroadcast

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy (First edition). New York: Crown. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQHs8SA1qpk&list=PLUp6-eX_3Y4iHYSm8GV0LgmN0-SldT4U8&t=1032s

O’Neil, C. (2017, July 16). How can we stop algorithms telling lies? The Observer. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/16/how-can-we-stop-algorithms-telling-lies

Santa Clara University. (2018). Lessons from the AI Mirror Shannon Vallor. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40UbpSoYN4k&t=1043s