In week six, we were tasked with exploring the ‘breakout of the visual’. Gunther Kress, the Australian semiotician, laid our foundation by suggesting that visual elements are more than simple decorative pieces but rather true modes of representation and meaning that influence symbolic messaging (Kress, 2005). So much so, that these visually discernible features could define what we understand as a type of new contemporary literacy.

What then do we make of those little emotion icons we know as emojis? What (grammatical? written?) conventions are we to use if we were to create a narrative using only emojis? Jay David Bolter, in his book The Breakout of the Visual asserts that picture writing simply lacks narrative power; that a visual plainly means too much rather than too little (Bolter, 2001). As a result, it can become increasingly difficult to write a narrative using visuals alone – it’s easy to convolute the communication of character relationships and development, the sequencing of plot points, the passage of time, or the overall narrative flow.

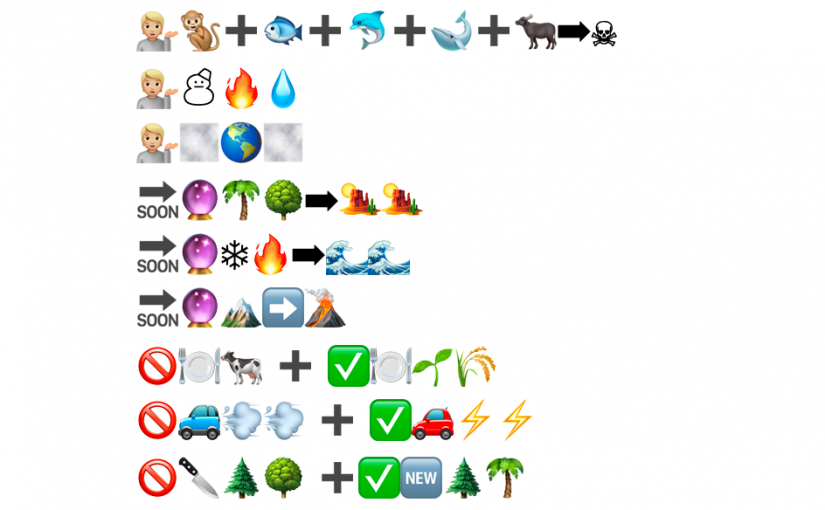

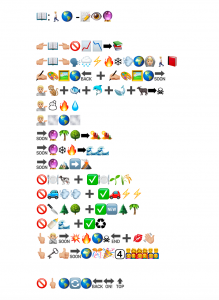

Consequently, it proved interesting to peruse my colleagues’ emoji stories and analyze the way in which they decided to construct the narrative form. Ultimately, I felt that Judy Tai’s transcription of Ratatouille held a multitude of similarities with respect to the architecture of an emoji story in comparison to my arrangement of A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and Vision for the Future. While some participants chose the classic horizontal familiarity that comes from reading books, many others like Judy and myself, chose a vertical approach to projecting some approximation of narrative continuity. Among other blog posts, the most frequently mentioned factor was the difficulty in transcribing singular words into emojis; rather, authors needed to conceptualize a group of words or meanings and represent it with a chosen emoji image. Oftentimes, even this strategy proved difficult and some people had to simply revert to searching to images that offered readers expansive interpretations.

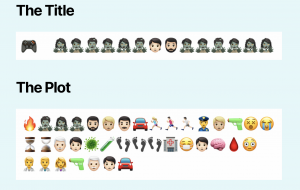

The first and perhaps most obvious link, was both Judy and I took a vertical arrangement approach to conveying the central notions of our stories. It seems both Judy and I instinctively appealed to some semblance of linearity and order, just as the traditional written commands readers to follow a strict order of comprehension (Kress, 2005), when we began our synopsis’ with a signal of the medium, and a corresponding title. When comparing this manner of structure with other colleagues, it became evident that this approach was the most common manifestation of architecture with respect to an emoji story. As far as I am aware, there are no formal conventions on how to construct a narrative consisting of solely visual aspects, like emojis. Therefore, it seems interesting to me that the default pattern of assembly was through vertical methodologies; perhaps more fascinating is the deep contrast between content and form in writing with visuals. Although there are many similarities between both our emoji stories, it seems like Judy’s images are a lot more spaced out than mine. In comparing them, I feel like my story is attempting to jam a lot more information into each line, while Judy is more delicate with the chose information. Despite these types of electronic hieroglyphs representing an extremely new medium of communication in human history, our automatic reaction was to revert to the style of the scroll.

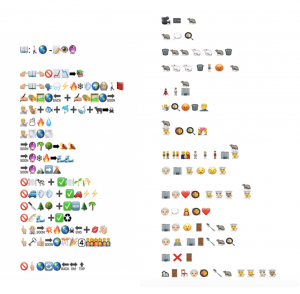

Comparatively, only a few participants in the Emoji story task utilized a horizontal approach to arranging their synopsis’. For example, Anne Emberline’s story took a linear form, similar to that of traditional writing structures. Anne was unique in that she opted to relay her story using image after image, attempting to build meaning using the fundamental processes of reading and writing we currently use. Interestingly, one of the things I commented on Anne’s posting was that although I totally comprehended what her narrative meant, I had no idea what exactly was the movie, game, book, or show. Consequently, this put Kress’ assertion of “that which I can depict, I depict” (Kress, 2005). at odds with our interpretations as I have only negotiated an insubstantial meaning specific to me, while others could infer something completely different, or alternatively, nothing at all.

What exactly prompts this style of organization? Why was it that most used line breaks to separate ideas, while others simply rattled off emoji after emoji with the hopes of creating meaning. I believe there is something to be said about our semiotic abilities to discern direction and instruction from punctuation. Writing is a marriage of words and symbolic markings, both of which direct meaning making within our minds as we decipher information through written words. With respect to the emoji stories, it is my interpretation that each line break indicated a new idea, new sentence, or new concept. I had a more difficult time deciphering Anne’s story than I did Judy’s.

Finally, Judy makes a compelling argument regarding the addition of images to text (in the form of graphic novels) becoming a driving factor for the increased interest levels of young readers. She posits an interesting connection between our human ability to read emotion and facial expressions as a means of inferring deeper about a particular story. While I agree with her assertions, I can’t help but think of some of the defining principles of Jean Piaget’s cognitive development model – I believe that at a certain point, our human minds crave a new challenge as they can formally operate within deeper texts; the image/word relationship begins to become commonplace. Moreover, our processing of both text and image pertains strictly to the visual sense. While Bolter makes this word/image relationship case with respect to internet models of publication, I can foresee a bit of a harkening back to the age of orality, where some of our future texts will be truly multi-modal; demanding an aural, visual, tactile, and perhaps even our gustatory or olfactory senses.

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kress (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, Vol. 2(1), 5-22