The last week of ETEC540 proved to be one of the more creative weeks in the course, and as some of us round out the final tasks before the end of our MET journey, the light at the end of the tunnel starts to look increasingly closer. The speculative futures task challenged us to creatively formulate a vision of the future with specific focus on the relationship human beings will have with technology, education, media, and various types of text. It was interesting to see most of my colleagues visualize this relationship as on a similar trajectory, appealing to common concepts and technologies, and transforming the world socially, politically, and culturally.

I endeavoured to consider AI in the distance dystopian future, attempting to warn of the potential rise of authoritarian type societies. The basis for my short story was Harari’s idea of the ‘useless class’, magnifying what that truly may look like in a neo-Marxist future. In this speculative future, the rise of AI algorithms have automated most of the middle class jobs, leaving two parties – the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. Essentially a new age proletariat vs. bourgeois story, the narrative reflects on the thematic role of text, technology, and education within this future. Education has become reserved for those ‘worthy’ and those not considered to be in that category are left to fend for themselves. In this cultural shift, the fundamentals of education have significantly changed, harkening back to more primitive and naturalistic forms of knowledge (ie- foraging, hunting, farming) whereas the more privileged technology users would obtain occupations ‘behind the AI scenes’, programming, coding, etc. The divide created by algorithms and AI was immense and immeasurable.

At the heart of the story is the imperative that the human capacity to create the algorithms embedded within AI technology requires deep and intentional ethical considerations, and needs to be utilized for the right reasons, by the right people.

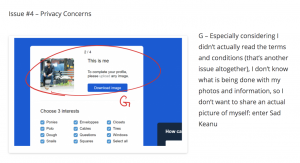

Similarly, I found that some of my colleagues appealed to analogous future circumstances. For example, Megan’s vision of the AI-enabled future was home to an app-based survey meant for middle class workers who had suffered job loss as a result of the increasing automation in society. The AI analyses the user- inputted information, runs it through an algorithm and generates a prediction with respect to the likelihood of success in a new industry. In both our speculative futures, we’ve envisioned an AI making important decisions for human beings, essentially dividing and sorting them into industries or factions, that have deep cultural and societal implications based on certain personal factors.

Alternatively, Megan and I differ when it comes to the factors involved in making these decisions. I propose that genetic predispositions and relevant biomarkers will play an important part in the analysis of information, which will enable AI to make more rational, sound, less discriminatory positions; a more optimistic view of the improvements that will be made to algorithms, despite the dystopian setting. Comparatively, Megan claimed that racist and sexist discrimination will be perpetuated to a higher degree within future algorithms despite not including ‘race’ in the work reassignments survey. This prompts me to question how these modes of discrimination could be perpetuated in the first place. It’s my presumption that this information was meant to be reflected in each user’s name, but a quick Google image search for “Justin Scott” would produce contradictory results.

Likewise, James produced a vision of the future that commented on middle-class occupations becoming overwhelmingly influenced by automation. He also engaged with the idea that most jobs available would be ‘behind the scenes’ as people would have to learn how to code, program, and/or have influence in directing the ethics around AI-enabled technology. I appreciated James’ characterization of the work force as completely on edge, where workers have secured limited positions on a short term basis’ and their continued overworking may only potentially yield success.

Of course, when we begin dealing with the concept of people programming, coding, and managing the direction of AI-algorithms, we must be vigilant in assessing the inherent biases. We’ve frequently seen the often unconscious prejudices built into AI technologies, and we need to be extremely careful in ensuring that these are corrected as AI continues to take hold of the future, especially when we are dealing with language and culture.

There is utility in discrimination and it’s exceptionally important to balance the levels of distinction we bring with us in the future. Discrimination is the recognition and understanding of the difference between two things – This is not a negative concept. We discriminate against all other potential partners when we choose an individual to take as our significant other, for example. We discriminate against all other animals, or all other breeds when we choose a specific breed of dog as our pet. Discrimination becomes a problem when it turns into prejudice – the unjust treatment of the aforementioned recognition. This we must leave in the past.

Regardless, it was interesting to recognize that my colleagues utilized some similar ideas presented in Yuval Noah Harari’s article Reboot for the AI Revolution. We’ve all touched on the potential for the ‘useless’ class, a faction of people who’ve been booted from their occupations due to automation and AI-enabled technology. Our differences resided in the factors embedded within the AI algorithms and the ways in which it decides to make decisions.

Hariri, Y. N. (2017). Reboot for the AI revolution. Nature International Weekly Journal of Science, 550(7676), 324-327 Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/news/polopoly_fs/1.22826!/menu/main/topColumns/topLeftColumn/pdf/550324a.pdf