It seems the evolution of the written word and the manufacturing of the materials needed for it has a long and convoluted history. The scroll, for example, was the main mechanism by which writers housed and organized the written word, often on one of three primitive writing materials: papyrus, parchment, or paper. It warrants considering the differences between the three:

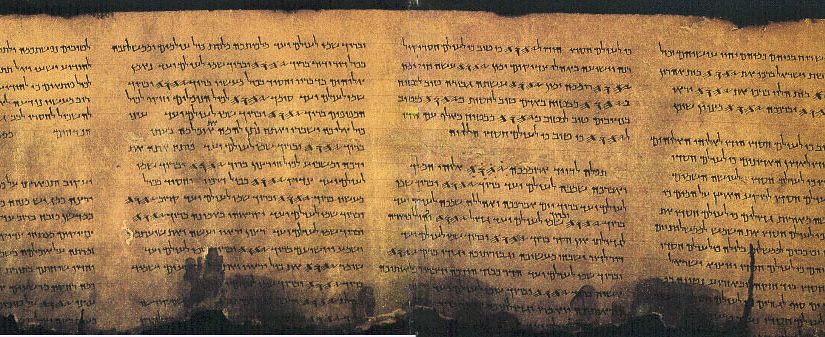

Papyrus: Made from the stems of the papyrus plants native to Egypt. Prepared by cutting ribbon like strips and placed on top of one another to be pounded together into what we would consider a sheet. Difficult to write on due to its rough fibrous nature and was liable to fall apart over time.

Parchment: Made from the untanned hides of animals. Became the more desired alternative to papyrus due to its ability to endure longer and because it provided a smoother writing experience. Used in roughly the same period as papyrus, but the dynamic relationship between these two types of writing styles allows for the interpretation that papyrus and parchment could be indicators of social status.

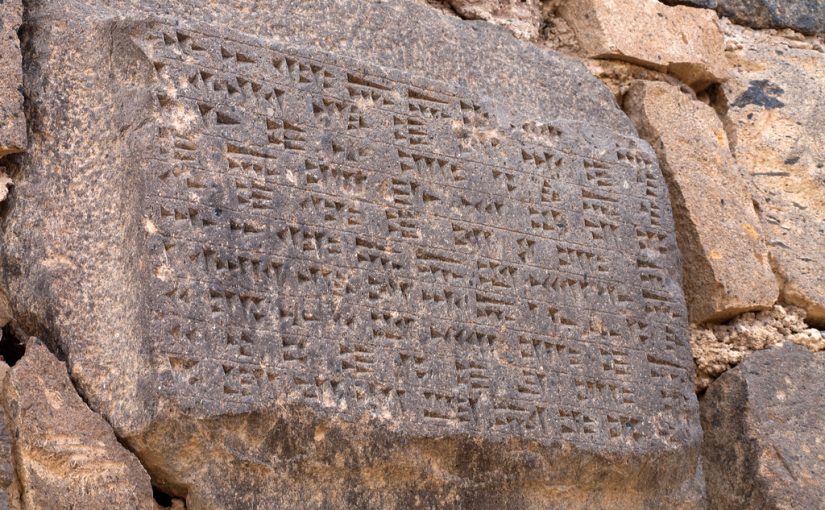

Paper: What we know as today’s paper was originally manufactured in China. Production is believed to have originated from pounding rags in water and tree bark. The fibres and pulp would collect on a mat screen and dried in the sun.

The scroll itself refers simply to a rolling up of one of the aforementioned writing materials. Inherently, there are both advantages and disadvantages to this mode of writing technology but it’s clear the disadvantages vastly outweigh the benefits, otherwise, we’d still be using scrolls. I believe the most evident benefit the scroll has is its portability – Scrolls were quite easy to transport, however, they took up a lot of space when trying to store. Additionally, scrolls made it difficult to locate desired passages or sentences as there were no ‘page numbers’ to accurately locate and organize written ideas.

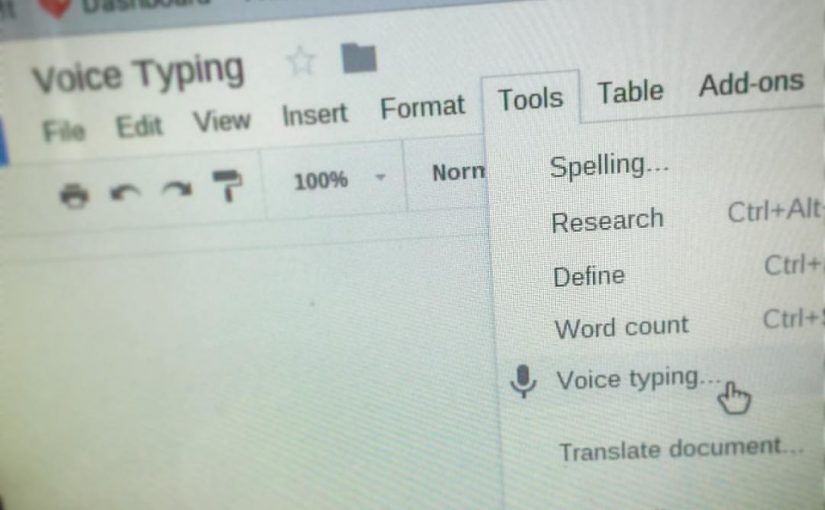

Consequently, like most media, advances and enhances to the technologies typically have some evolutionary birthmark if we look close enough. Marshall McLuhan famously contended that most new media innovations evoke content fundamental to the earlier forms of related media. He called this the rear view mirror effect, whereby individuals use old terminology or concepts to aid in the navigation of innovative forms of technology.

“Ordinary human instinct causes people (…) to rely on the rear-view mirror as a kind of repeat or ricorso of the preceding environment, thus insuring total disorientation at all times. It is not that there is anything wrong with the old environment, but it simply will not serve as navigational guide to the new one. (Through the Vanishing Point, xxiii)

This is an idea I’ve touched on in a previous blog posting – It’s no coincidence we still liken the power of car engines to the measurement of horses; it was once the horse drawn carriage. It’s no accident we use the metaphor of a ‘library’ to characterize a collection of online digital artifacts, or how the primitive stone tablet once used to record information has been borrowed to now refer to handheld technologies. This is certainly true for the scroll as well: Think about how we “scroll” from top to bottom through material on our phones or when we read through websites just as the early scroll users would have done.

Moreover, it seems the same issues plaguing the early scroll writers are pervasive in our own culture as well. One of the problematic design aspects of the scroll was it’s deliverance of uninterrupted information; it was essentially one remarkably long page of writing. Today’s websites seem to be running into the same debate when dealing with web design; there are cultural consequences in relation to the selection of such design. For example, continuous scrolling web pages enable higher degrees of interactivity, especially within an ever-increasing mobile society.

When the scroll evolved into the codex, so too did the function of reading and thought. Rather than invoking continuous principles of writing, the codex brought about discontinuous thought and paged writing. I recall Lera Boroditsky’s article about how language shapes thought and her research that outlined how people from the Kuuk Thaayorre culture viewed representations of the past and present differently from people who thought and read in a more linear fashion (Boroditsky, 2011). The move to the codex, first and foremost, codified information for accessibility and ease of future retrieval. It could be opened to any point in a text, was much more durable than its counterparts, and also permitted the use of both sides of the paper. Perhaps most importantly was the cultural positioning and societal stature that the codex reflected of its owner, especially in the context of Christianity. It’s worth noting that the invention of the codex did not wholly overtake the use of the scroll. In fact, it wasn’t until the invention of the printing press that the use and manufacturing of codices truly took off.

Through a socio-cultural lens, the printing press revolutionized, and in some ways, democratized knowledge by making widely available written text. With its inherent ties to Christianity (the first book manufactured was the Bible), the production of books increased literacy levels throughout Europe while simultaneously increased membership of the Christian faith. I can’t help but wonder the various ‘new literacies’ we currently obtain when innovative technologies are presented to us…

Boroditsky, L. (2011). How language shapes thought. Scientific American, 304(2), 62-65

McLuhan, M., & Parker, H. (1968). Through the vanishing point: Space in poetry and painting. New York: Harper & Row.