Week 4 prompted some ETEC540 students to write a diary-style entry or reflection of approximately 500 words. Typically, this is no sweat for a graduate student, but the challenge this week was that this writing must be done manually. It’s interesting to me that me and my colleagues seemed to endure much of the same experiences despite a seemingly large generational gap between us.

When it comes to manual script writing, there seemed to be a consensus from a majority of my colleagues on a number of aspects:

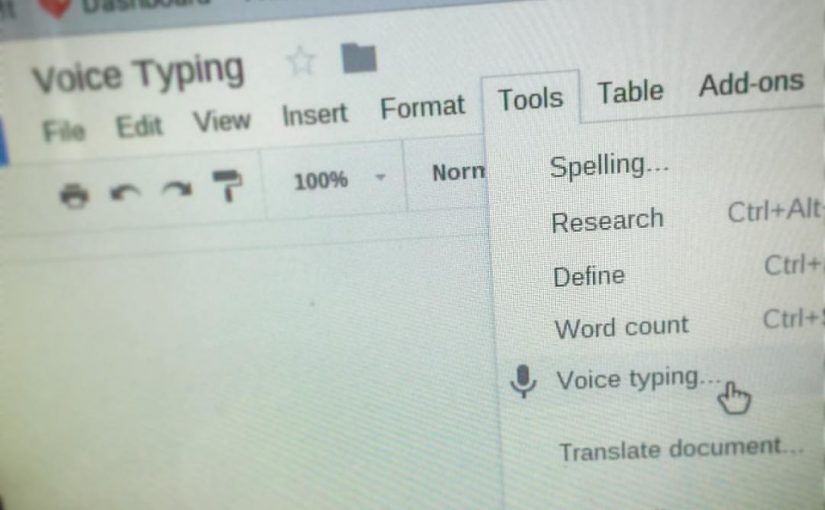

1) Most, if not all, of our professional writing is computer-generated and typed using a device

It seems clear that the most effective and ‘professional’ way to communicate in our various occupations is through computer-generated text. Greg Patton articulated that the writing he does for work, which was characterized as ‘formal’, is done overwhelmingly on the computer. Deirdre preferred typing when dealing with assignments, lessons, or “anything that requires professional or formal” types of communication. Ying, interestingly enough, characterized manual writing as “reserved for the most special recipients, those truly worth our time… only done on heartfelt messages like love letters and thank you notes”. I will certainly be rethinking the next time I need to send a text to my partner, or perhaps my boss: “Maybe I should hand write this and mail it?”.

Our current culture has dictated that the most suitable means of communication is through some form of digital text. Why? I think Deirdre summed it up pretty well: Typing affords users an unparalleled speed in comparison to manual scripts, furnishes users with the ability to edit and correct text leaving it unblemished, and bestows writers with a simple mechanism for sharing and sending information. Although Ying’s criteria is well-intentioned, it positions those who regularly receive non-manual scripts as ‘unimportant’ and creates a false dichotomy between individuals who inhabit a hierarchy of ‘importance’ and those whom an individual considers “worth their time”. Consequently, I found it shocking to hear that “career excellence is impossible with a child” and “women who place career over their children are ostracized by society”. First, I think the portrayal of career excellence here is exceptionally vague – What does excellence look like? I’m not sure this is a completely objective term. Is this a concept that applies to both sexes or only women? As for the repudiation of career-driven women from society, I’d be interested in hearing exactly what benefits are stripped from individuals who find themselves in this position. Would this ostracization occur if the career was the sole means of facilitating a suitable life for a child? Do men also find themselves excluded from societal advantages if they are exceptionally career driven? Is this truly a gendered issue or is this simply about the choices we make with respect to careers and families?

2) There is aesthetic beauty, ugliness and physical limitations to hand written material

Perhaps overwhelmingly mentioned was the inherent aesthetic of hand written material. Ying alluded to the fact that hand written material should be reserved only to those special to you, which also implies there is a certain charm and desirability to it. Perhaps Deirdre elucidates a more responsible criteria: hand written material is simply reserved for something or someone more personal. With that said, the intrinsic beauty embedded within manual writing can turn unattractive quickly when a manual script is marred with corrective edits, scratches, or misspelt words. Ying does a great job in expressing how these textual imperfections make the product look tarnished, draws unnecessary attention, and potentially leaves evidence that reflects lower intelligence levels (although not entirely convinced of that last one – should we consider students who have severe dyslexia to have lower intelligence levels?).

Using a pencil with an eraser, although helpful in eliminating these aesthetic blemishes, will not aid in producing a completely flawless product as scars are still left behind, albeit minute. Fundamentally, there is no room for major error in order to manufacture a beautiful piece of writing. Moreover, it needs to be legible! The physical limitation manifests itself specifically in hand muscle cramps or corporeal damage like the writer’s bump Deirdre mentions. These are factors of manual script writing that simply slow us down.

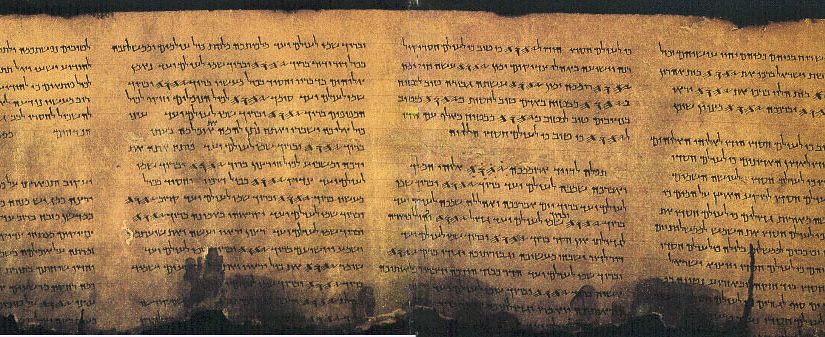

3) Written texts are mnemonic in nature

Both Deirdre and Greg conceded that written texts are most helpful when the desired effect is to remember something. Greg describes his habit of leaving numerous post-it notes on and around his desk in order to remind him of certain tasks or items. Likewise, both Deirdre and I claimed to write out our grocery lists; we do this in shorthand or point-form as a means of saving time and mental/ physical energy. Research suggests that there are mnemonic elements related to the tactility of the written word:

“Writing is a process requiring the integration of visual, proprioceptive (i.e., haptic/kinesthetic), and tactile information… There is evidence that writing movements are involved in letter memorization… that is, we write in order to remember something” (Mangen, 2015).

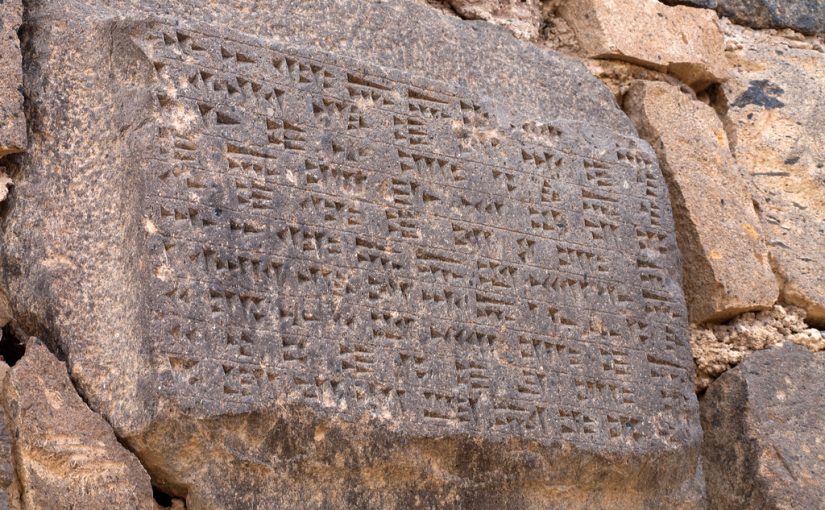

Despite all these similarities, there was a stark contrast I noticed when analyzing the generational divide between us all. Greg, for example, conveyed that he is consistently able to write faster than he can type. He concedes that his typing skills are lacking, and that he uses “2-3 fingers” to type words on a keyboard. Along the aforementioned lines of writing and tactility, Greg iterates that he appreciates the “feel of holding a finished copy in his hand… [he] thinks this is because [he] is an older guy and hasn’t embraced technology to some of the younger generation’s degree”. Comparatively, both Deirdre and I find ourselves on the farther side of the millennial spectrum and we both can remember working with both pen and paper, and a computer in school. The manual script exercise made us feel nostalgic, while Greg simply felt more comfortable, even in a position to excel. We certainly did not feel like we could write faster than we could type as we both spoke about the rate in which we could produce typed text.

To me, it’s evident that there is a tangible generational difference in perception, ability, and comfort when it comes to manual writing. Writers from an older generation are forced to embrace new media and harness novel tools in order to survive, at least in a professional context. Comparatively, millennial writers for example, are unique in the sense that they were born into a transitional age, wherefore these tools no longer were novel, but rather, sensible and commonplace and used in conjunction with their counterparts. It’s no wonder the written word is thought to be reserved for the personal; the new generational members were not around when the written word was the commonplace medium for textual communication.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mangen, A., & Anda, L., & Oxborough, G., & Brønnick, K. (2015). Handwriting versus keyboard writing: Effect on word recall. Journal of Writing Research. 7. 227-247. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2015.07.02.1.