Task 8 | Golden Record Curation

Introduction

According to the Twenty Thousand Hertz (n.d.), each of 1977 Voyager (I & II) includes a Golden Record that serves as a time capsule, intended to communicate information about our world to extraterrestrials, if they happen to discover, hear, and decode it as well as understand what these signals mean to us. With a contemplative eye on Smith’s (2017) compelling lecture, the NASA project seems to hold a strong connection: The voice from humans’ past would be projected into an imagined future. So, Carl Sagan and his team were faced with questions: what is important to collect? What would aliens want to know about the past in the future? What can they afford to save? The Golden Record was recorded on a gold-plated copper phonograph disk; the analog technology has the advantage of longevity (the records are predicted to travel unharmed a billion years) and the disadvantage of limited space. The disk holds 115 analog encoded photographs and sounds of animals and humans on earth and a curated list of 27 musical tracks from cultures worldwide (NASA JPL, n.d.). This week we are asked to curate the 27 tracks further into ten items.

As I listened to the musical collection, I have thought that the inclusion of human music-making through this historical artifact is an admirable attempt. Carl Sagan and his team claimed they had sought a holistic portrayal of our species and a representation of cultural diversity (Nelson & Polansky, 1993). Timothy Ferris in the Twenty Thousand Hertz Podcast added, “We tried to get music from all around the world, not just from the culture that had created the spacecraft” (Thousand Hertz, n.d.). However, I wondered why there are three examples of Bach and two of Beethoven if the goal is diversity and the space is limited? The several pieces of the same composer crumpled the utopian idea and heightened the doubts.

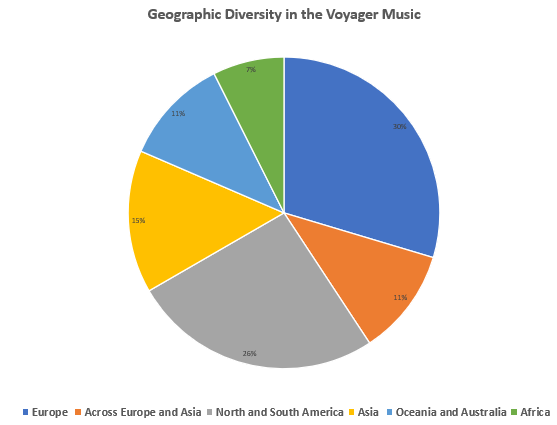

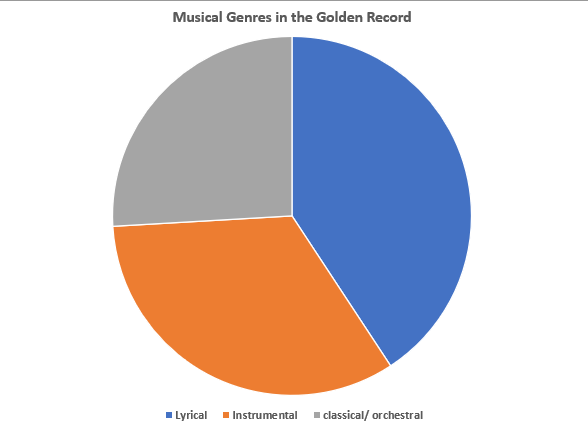

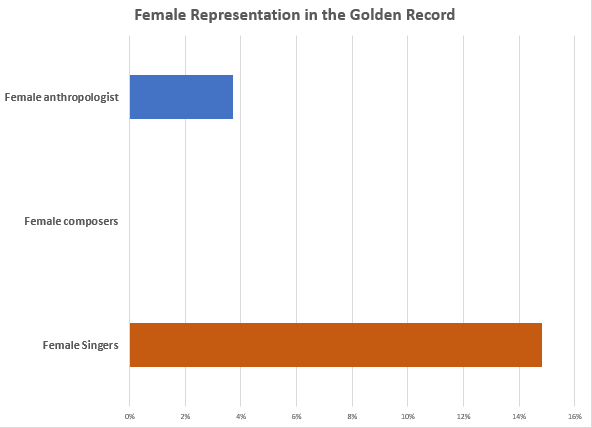

For a clearer picture, I organized the information of the tracks in a spread sheet. This helped me to dissect the Golden Record collection numerically from three different angles: [1] Geographical representation. [2] Musical genre (orchestral, instrumental, and lyrical). [3] Gender representation. See the figures below:

The visuals reveals Western musical and geographical biases as well as imbalanced gender representation. There is an obvious over-representation of the European classical music that is the musical heritage of the culture that built the spacecraft; this proves Smith’s (2017) viewpoint “we are very much creatures of the worlds in which we grow up.” Moreover, the collection is overly biased to individual male composers, musicians, and ethnomusicologists except for the Australian piece and few pieces sung by female vocalists. From a content analysis perspective, the selection is limited in a constrained historical period and tonal styles (Nelson & Polansky, 1993). Besides, the choices conform to male gender-norms and conventions, such as Georgia’s drinking song. Furthermore, for Non-western pieces, the attribution is fully credited to the ethnomusicologists (e.g., Java, court gamelan, “Kinds of Flowers,” recorded by Robert Brown), but who are the real property holders (i.e., artists)? Why the reference tend to simply named by ethnic group or country of origin? In an article entitled “Beyond the morning star: the real tale of the Voyagers’ Aboriginal music”, Gorman (2013) reveals the attribution inaccuracy of the Australian Aborigine second song (Devil Bird) in the official NASA site. She stated that the second song is not the “Devil Bird” song, but “Waliparu singing Moikoi” (para. 14). “This lack of proper attribution of Non-Western is a frequent occurrence (Diamond,1990)” (as cited in Nelson & Polansky, 1993, p. 361).

My ten tracks

I used my spreadsheet groupings as a guide in selecting the 10 tracks out of the original 27. I wanted to be as inclusive as possible. For that, I started by selecting one track from each continent. Then I tried to regard the diversity in terms of the of music genre, instruments, and gender representation. However, I admit that this list is still exclusive and limited by the biases of the original list. Below is my ten tracks visual on a world map.

| Selected pieces |

Reasoning |

| 1- Mozart, The Magic Flute, Queen of the Night aria, no. 14. Edda Moser |

|

| 2- Stravinsky, Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance, Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Igor Stravinsky, conductor |

|

| 3- Bulgaria, “Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin,” sung by Valya Balkanska. |

|

| 4- “Melancholy Blues,” performed by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven

|

|

| 5- Mexico, “El Cascabel,” performed by Lorenzo Barcelata and the Mariachi México. 3:14 |

|

| 6- Peru, wedding song, recorded by John Cohen. |

|

| 7- Senegal, percussion, recorded by Charles Duvelle

|

|

| 8- Australia, Aborigine songs, “Morning Star” and “Devil Bird,” recorded by Sandra LeBrun Holmes.

|

|

| 9- Japan, shakuhachi, “Tsuru No Sugomori” (“Crane’s Nest,”) performed by Goro Yamaguchi. |

|

| 10- India, raga, “Jaat Kahan Ho,” sung by Surshri Kesar Bai Kerkar |

|

Final thoughts

Data storage and documentation has allowed the Voyager Golden Records to have many afterlives, musical and otherwise, since 1977. Today, we can view, listen, download, and analyze all its visuals, footsteps, heartbeats, and music throughout the digital representation or segregates. However, despite the remarkable rise in technological capability, we need to be cautious; digital data is only a sampling of the original information that is then encoded into the 1s and 0s that a computer understands (Smith, 2005; Shehata, 2019). The digitalization of the Golden Record has reasonably entailed a loss of information and a high cost to represent the original as closely as possible. Would we be able to tell the significance of data loss in the music that we heard? Only if we can hear the sounds emitted from the golden disk itself.

Now in the age of digital, the documentation and storage challenge is more profound than in the analog age of the Golden Record production: How is it possible to save the unprecedented amount of digital artifacts for the future generations to learn about? How many zettabytes, and how many square feet of server rooms and data center audits are necessary to store and maintain access to historians? And how about the “unanswered questions” about data authenticity and stewardship/ privacy and liability concerns? (Smith, 2017). Honestly, I can’t see the entire digital wealth pressing into the future as long as the “new oil” is in the possession and control of the technology vendors, the business measures of what is important to keep is distinctive from that of historians, researchers, and scholars like Abby Smith; what will be revealed about the current epoch to the future generations will be an insignificant percentage of the digital archive. I will leave it here with an important tale: The Library of Congress experience with the Twitter archive.

References

- Gorman, A. (2013). Beyond the morning star: the real tale of the Voyagers’ Aboriginal music. The Conversation. Retrieved from Beyond the morning star: the real tale of the Voyagers’ Aboriginal music (theconversation.com)

- Hart, H., & SpringerLink ebooks – Literature, Cultural and Media Studies. (2018). Music and the environment in dystopian narrative: Sounding the disaster. Palgrave Pivot [Imprint].

- Kara, M., & Teres, E. (2012). the crane as a symbol of fidelity in turkish and japanese cultures. Millî Folklor, 12(95), 194-201.

- Morena, A.(2019). Voyaging: The “Wedding Song” Singer, Citations, and Space Junk. Misreader. Retrieved from Voyaging: The “Wedding Song” Singer, Citations, and Space Junk | by Misreader | Medium

- Nasa JPL (n.d.). The Golden Record. Retrieved from Voyager – The Golden Record (nasa.gov)

- Nelson, S., & Polansky, L. (1993). The music of the voyager interstellar record. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 21(4), 358-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889309365379

- Shehata, O. (2019, May 1). Unraveling The JPEG. Retrieved June 15, 2019, from Parametric Press website: https://parametric.press/issue-01/unraveling-the-jpeg/

- Smith, A. (1999, February). Why Digitize? Retrieved June 15, 2019, from Council on Library and Information Resources website: https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub80-smith/pub80-2/

- Smith, A. (2017). Abby Smith Rumsey: “Digital Memory: What Can We Afford to Lose?”[Video Post]. Retrieved from Abby Smith Rumsey: “Digital Memory: What Can We Afford to Lose?” – YouTube

- Toronto Public Library. (2011, April 2). The Bulgarian folk song „Излел е Дельо хайдутин” in Space (Voyager Golden Record) [blog post]. Retrieved from The Bulgarian folk song „Излел е Дельо хайдутин” in Space (Voyager Golden Record) – Arts & Culture (typepad.com)

- Twenty Thousands Hertz. (n.d.). #65 | Voyager Golden Record. Retrieved from Voyager Golden Record — Twenty Thousand Hertz (20k.org)