Brief

The purpose of the task is to critically examine the role of equity, diversity and inclusion within the context of makerspaces, while incorporating decolonization and anti-racism frameworks through the examination of the content in MET’s Anti-Racism Speaker Series. Design a maker challenge or provocation that fosters an environment of equal participation, cultural understanding, and social justice within the makerspace community.

Choose one Anti-racism Speakers Series presentation or podcast to frame the challenge/provocation. Make note of key ideas, theories and research presented in the series. This challenge/provocation should actively promote the participation of individuals from diverse backgrounds, including those historically marginalized and under-represented in the field. Integrate cultural sensitivity and awareness into the design process, ensuring the activity is respectful, accommodating, and accessible to all participants. Use the following templates to design the challenge/provocation.

Inclusive Maker Challenge Template

Inclusive Provocation Template

Find the full Word document here:

Pedal Perspectives – Navigating Bike Culture Through Gender, Race, and Justice

Overview of Provocation

This provocation is designed to encourage students to explore the local bike scene and explore how community, identity and inclusivity intersect in cycling culture.

In Pedal Perspectives, students are encouraged to read some bike zines, visit their local bike shops, meet local riders and perhaps join a biking event, and consider the ways that these spaces are — or are not — accessible and welcoming. How do gender, race and identity shape our experiences in these spaces?

While cycling has surged in popularity as a mode of transport, fitness and community engagement, scholarly research on bike culture remains scarce. Traditional academic circles often overlook the nuanced, lived experiences of cyclists, especially those from marginalized groups.

In conjunction with the Anti-Racism Speakers Series podcast Pervasive Racism and the 2SLGBTQIA+ Community, guest speakers Alex DeForge and Meera Dhebar talk about the lack of meaningful representation, the impact of stereotypes, and need for more intentional and inclusive effort to reflect diverse identities. Both speakers emphasize that critical literacy is the key to empower individuals, and to understand the diversity and depth of the bike community, we need to explore beyond mainstream publications and delve into more underground and personal spaces – like zines.

“The history of lack of women, LGBTQIA+, and BIPOC representation in cycling reveals their marginalization and exclusion, especially in cycling media and sport. And it speaks to a bigger cultural issue of how marginalized groups are continually ignored and misrepresented. We cannot shy away from telling our stories in cycling just because it doesn’t suit the narrative the cycling industry sells.” (Cyclista Zine, 2019)

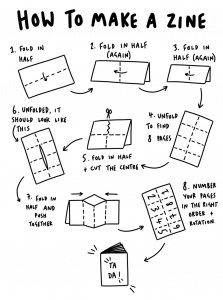

Zines are booklets (like magazines) that are used to share information, knowledge or experiences with others. They are often made with pen, paper, and collage techniques. They can also be made on computers using digital publishing software.

These DIY publications offer a more authentic look at the voices, struggles and triumphs within biking subcultures, often addressing topics such as gender identity, race, accessibility and social justice that are otherwise absent in academic discourse. By engaging with zines, we can gain more personal and grassroots perspectives that shape biking culture, and illuminate the vital, under-represented voices that mainstream studies miss.

Through guided reflections and interactive exploration, and creating your own zine, this project encourages students to investigate how their own backgrounds and identities relate to the biking community, in hopes to start a conversation about inclusivity, equity and what it means to belong and participate in a community.

Materials and Resources Required

-

- Device (computer, tablet, phone) to take notes or document reflections

- Pencil, pens, paper, magazines, flyers, art/craft supplies etc.

- Optional: access to a bicycle

Inclusive Maker Provocation Instructions

Part 1: Pre-activity Reflection — Understanding your own positionality in bike culture

Think about your current experiences and knowledge when it comes to biking and bike culture. By reflecting on these questions beforehand, you can better understand your personal lens and become more aware of how your own experiences and identities shape the way you engage with biking spaces and community interactions.

Some questions to consider:

-

- What is your personal history with biking? Do you view it more as a form of transportation, recreation, fitness or something else?

- How often do you engage in biking activities, and in what kinds of spaces (i.e. recreational trails, urban commutes, group events)?

- Have you experienced barriers to accessing biking spaces, whether economic, social, physical, etc.? How have they shaped your relationship to biking?

- Do you see people who share your identity and background in biking spaces you frequent? How does this affect your sense of belonging?

- Are there stereotypes or assumptions within biking culture that impact on how people perceive you or that shape how you perceive others?

Part 2: Participate —

Visit your library’s zine section

-

- Visit your library’s zine section, and browse the selection of bike-related zines

- Select a few zines to read, pay attention to the different voices, styles and stories represented

- Take notes on reoccurring themes, especially in relation to gender, race, accessibility or personal experiences in the bike community

Some questions to consider:

-

- Who is the author and how does their background and identity impact their experiences within the bike community?

- How do the perspectives in the zines compare with the mainstream cycling media or bike shops?

- What issues or themes appear frequently across the zines? What is something novel or surprising that you’ve noticed about the zines? What are some themes that you can relate to personally?

- How do the zine creators express their identities and experiences through their zines? Are there recurring challenges or barriers that they discuss?

- How do the zines influence your understanding of the biking community? How does that affect your perspective of your understanding of the bike community?

If you do not have a zine section at your local library, consider reading through online eZines related to bike culture, here are some recommendations:

-

- Cyclista Zine Library : a collaborative zine made from intersectional feminist and DIY culture lens. It is run by zinester Christina Torres and celebrates intersectional feminism through zines, live events and workshops.

-

- QZAP: Queer Zine Archive Project – Dykes and Bykes

-

- Microcosm Publishing Bike Zines : should you have the funds and means, check out some bike zines Microcosm Publishing, a zine publisher based in Portland, Oregon.

Part 3: Create — Record and share your experiences in a zine

-

- Follow the instructions above to make a simple one-page zine as a base to document your reflections from the previous activities.

- Embellish your zine with illustrations or make a collage with my arts and crafts supplies that you have available.

Some additional resources:

The Creative Independent – How to Make a Zine

Critical Questions for Consideration

-

- How do you feel about entering spaces that may be new or unfamiliar? Are there any assumptions or expectations you hold about bike shops, biking events, or zine culture?

- In what ways are you open to letting this experience challenge or expand your existing views on biking culture, inclusivity, and community dynamics?

-

- In what ways could this provocation be adapted to other subcultures or community activities where marginalized voices are underrepresented? How might this broaden students’ understanding of inclusivity in various societal domains?

Background/Additional Information

Inclusivity Focus

This challenge considers the EDIDA framework with emphasis on exploring biking spaces in relation to the student’s own positionality, encouraging students to access who these spaces are designed to serve and who may be excluded or underrepresented.

The activity also includes diverse ways to engage with the biking culture and community (see Extension section below) – whether it is visiting a bike shop, attending an event, or exploration via zines — students with varying physical abilities, comfort levels and preferences can participate meaningfully.

Lastly, I have purposefully included zines as a source of learning as it engages with the decolonization framework by valuing non-traditional, grassroots forms of knowledge production and distribution. Zines often represent marginalized voices and disrupt dominant narratives, offering insight to biking culture and underrepresented voices often missed in academic literature.

No Tech, Low Tech, High Tech Options

Zines are quintessentially low-tech, DIY methods of sharing knowledge and experiences, easily made with pen and paper, and a photocopier if you would like to share and distribute your zines!

Some higher-tech options for sharing similar kinds of DIY content include:

-

- Blogs/Personal Website

- Digital Zine/eZine

- Social Media

- Podcast/ Youtube Channel

Extension

Choose an activity below and follow the guiding instructions to help reflect on your experience. These activities are made to include a broad range of involvement and participation, and are mindful of certain barriers, such as access to a bicycle, different levels of mobility and skill levels, and meant to expand in the different ways participation can look like.

Nonetheless, these activities and questions aim to deepen your understanding of the diverse, often overlooked experiences within biking culture and help you explore how your own perspectives interact with these communities. Enjoy the journey!

Visit a local bike shop

-

- Choose a bike shop near you and make a visit. As you explore space, pay attention to how the space is organized and who the shop seems to be designed to serve.

- Observe the shop’s environment, the types of bikes and gears available, and any information displayed about events or cycling groups.

- If possible, strike up a conversation with an employee to learn more about the shop’s role in the local biking community

Some questions to consider:

-

- Who does this bike shop seem to cater to? Are there specific demographics that seem prioritized in this set up, product offerings or marketing?

- What aspects of the shop make it feel inclusive or exclusive? Consider factors like pricing, layout and accessibility.

- How does the shop engage with local community? Do they advertise any events or promote social causes on their bulletin boards?

- How did you feel going into this space, what about it made it feel welcoming or intimidating? Did you feel comfortable being in this space?

Participate in a bike event

-

- Find a local bike event that is open to all skill levels, like a group ride or a community bike day.

- Participate in the event, look around and make note of the people involved, the event’s purpose and the general atmosphere

- Notice how newcomers are welcomed, and whether accessibility (in terms of skill level, gender, background) is addressed during the event

Some questions to consider:

-

- What kinds of people attended this event? Are there particular groups that seem well-represented or under-represented?

- In what ways was the event accessible or inaccessible to people with different needs or backgrounds?

- How did the event organizers foster a sense of community or shared purpose? Were there any efforts made to address diversity or inclusivity?

- How did you feel about participating in this event? How does your own identity and experience shape your sense of belonging or connection? Would you participate in a similar event again?