5 Ways that Ancient Literary Practices have Pervaded the Digital Literacy Shift

5 Ways that Ancient Literary Practices have Pervaded the Digital Literacy Shift

An eloquent quote from Frost (2000) stuck out to me from this Module’s readings: “The reading modes overlay and merge with each other. These are the modes of orality, writing, print and electronic transmission. They all emerge, persist and influence each other in a continuing, timeless dynamic of the storage and transmission of knowledge.” Although Frost was referring to the papyrus scroll, the codex, and the papyrus letter in the initial part of this selection, he adds later that this belief could be applicable to multiple transitions in text technologies over the last few centuries. This blog post is designed to analyze the evidence of ancient literary practices that “persist and influence” throughout our modern digital era (Frost, 2000). I will draw upon multiple reading selections to make the case that we continue to uphold some key ancient literacy practices despite our use of modern tools to aid in changing literary communication.

Prior to this analysis, I would like to point out that no single one of these practices, technologies, or social changes were directly caused by another phenomenon. To follow in Bolter’s (2001) assertion, “They shape and are shaped by social and cultural forces”, including practices passed down by ancestors or those widely adopted by society in general. I will divide my 5 major points into text-oriented and cultural evidence, respectively.

Text-oriented evidence:

- Evidence of pagination and numeration to organize online contexts

Online contexts are rampant with evidence of pagination. Have you done a Google search where you’ve actually needed to click on the second or third page of results? Have you read an article that was split into more than a single page? There are often numbers on the bottom to signify what page you are on and where to head next. What about numbered lists that make you want to click because it sounds so easy to consume? “10 Amazingly Easy Halloween Costumes” – that sounds great! Or perhaps this very post, which I’ve titled appropriately to draw in list-lovers like myself.

2. The online “printer’s mark” (Clement, 1997)

In his 1997 essay, “Medieval and Renaissance Book Production – Printed Books”, Clement discussed the use of “printer’s marks”, which “informed a prospective buyer at a glance that a book was the product of a known publisher.” The use of printer’s marks, or logos, to depict the brand of a published piece of writing is a commonality in the blogosphere. In fact, any writer can make their own mark, which could be as small as a signature (something I do at the end of my blog posts on my professional blog), or a logo such as Alice Keeler’s, which she created due to the popularity of her blog. Moving to a educational publishing groups with recognizable marks, we could include Edutopia, EdSurge, or CommonSense; some sources of various educational [technology] knowledge, among many.

3. The modern (interactive) table of contents

Clement (1997) also discussed the use of “tabula” or “registers”, which were tables that organized the content of the book; the predecessors to the modern table of contents. While the early user relied heavily on accuracy of the table as well as an understanding of pagination to reach their desired content, our modern table of contents do the work for us through hypertext links (Keep, McLaughlin, & Parmar, 1995). We have experienced the use of such table of contents in our course through Bolter’s (2001) social book along with Chandler’s (1994), or Keep, McLaughlin, & Parmar’s (1995) work.

Cultural evidence:

4. The persisting linear nature of texts (Bolter, 2001)

The linear nature of the scroll may have led Aristotle to his conclusion that “plot structure [has] a beginning, middle, and an end” (ETEC 522, Module 3, 2015). This attitude and practice maintained itself throughout most of text-based history, even in the digital age. Despite Bolter’s (2001) claim that “linear forms such as the novel and the essay may or may not flourish in an era of digital media,” I would like to confirm his following statement that “[w]riters generally still write with a single, fixed order in mind”. I believe that the nature of the text has changed mostly in its length and style; perhaps due to fleeting attention span, perhaps due to the nature of media production tools, or perhaps to reach a larger audience. However, whether you’re watching a YouTube video, reading a blog post, or perusing a news article, it’s likely maintaining some form of linearity, even if you have the option to hop between elements of the text as you consume it.

5. A return to academic print elitism

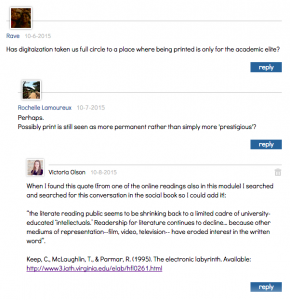

This point stemmed from great comments from Rave and Rochelle on the Social Book:

Keep, McLaughlin & Parmar (1995) highlight the fact that as digital texts begin to become more readily available, people are becoming less “interest[ed] in the written word”, and we are returning to an era of print literacy that belongs to a single class. This time, it belongs mostly to the educated class, contrasted with the upper class in the era of the manuscript as Keep, McLaughlin, and Parmar (1995) outline.

I believe that Frost (2000) was dead on in his statement that each new mode of literacy “overlay[s] and merge[s] with each other.” As we continue to adopt new technologies and new ways to read, write, and speak to one another, we also integrate some ancient practices of organization, branding, sharing, structure, and elitism.

References:

Bolter, J. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Chandler, D. (1994). “Technological or Media Determinism”. Retrieved from http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Clement, R. W. (1997). Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies, “Medieval and Renaissance Book Production: The Manuscript Book.” Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20140911024244/http://www.the-orb.net/encyclop/culture/books/medbook1.html

Frost, G. (2000). Futureofthebook.com: “Scroll to Codex Transition”. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20060511022155/http://www.futureofthebook.com/storiestoc/scroll

Keep, C., McLaughlin, T., & Parmar, R. (1995). The electronic labyrinth. Retrieved from http://www3.iath.virginia.edu/elab/hfl0261.html

Reading Week: The Scroll and Papyrus [ETEC 522, Module 3 Course Content,]. (2015). Retrieved from https://connect.ubc.ca/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayLearningUnit?course_id=_75468_1&content_id=_2913610_1&framesetWrapped=true