NLG – Writing from a place of privilege?

All academic writing must, in some way, come from a place of privilege. Academics are, by their very nature a type of elite, those with the most knowledge or expertise in certain areas of society. As such, they often take a tone that either purposefully or inadvertently talks down to the average Joe. Even if someone grew up on the street, made it to university through scholarships obtained through a combination of hard work and raw intelligence, by the time she is publishing papers she will have been in academia long enough to have entered the elite, even if she continues to argue for the underprivileged.

This is the case with the New London Group. They argue for multiliteracies for the benefit of communities or cultures on the fringes, or those with their own discourses that have been disparaged or ignored but now need to be valued. “To be relevant, learning processes need to recruit, rather than attempt to ignore and erase, the different subjectivities — interests, intentions, commitments, and purposes — students bring to learning” (NLG, 1996, p. 72).

The NLG are very critical of corporate culture and I wonder if writers from less-privileged nations would have had the same liberty. While it is true that even in the U.S., U.K., and Australia, corporations try to exercise their power over universities, universities maintain an awkward balance as bastions of left-wing, anti-corporate thought that are immune to the whims of these corporations while still preparing most of their student populations for corporate life. They can still bite the hand that feeds. One could imagine a C.E.O. cringing reading the line “Our job is not to produce docile, compliant workers” (p. 67) .

This dichotomy between depending on capitalism for survival while simultaneously trying to keep it in check is best manifested in the last sentence of the section Changing Working Lives, “Rather ironically, perhaps, democratic pluralism is possible in workplaces for the toughest of business reasons, and economic efficiency may be an ally of social justice, though not always a staunch or reliable one” (p. 68).

If scholars from, say, India, China and Brazil had written this paper in that same mid-90s time period, rather than those from the aforementioned English-speaking nations, I think, if anything, they would have been more polarized and may not have been able to come up with a document as coherent as A Pedagogy of Mulitliteracies. The situation in these countries of stratified economic distribution tends to be more hard-line, more Communist vs. Libertarian than Social Liberal vs. slightly-less Social Liberal.

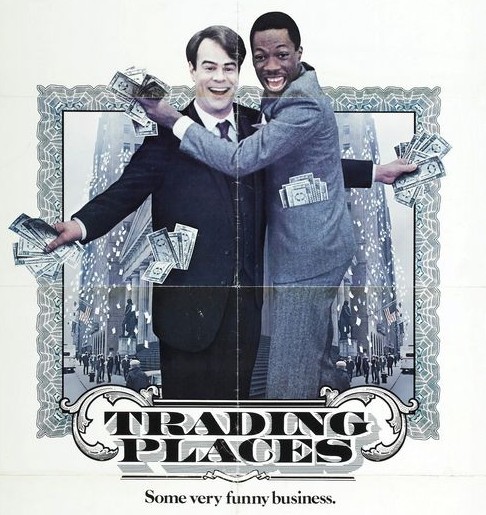

That being said, a probable lack of political and ethnic diversity among the 10 authors (I haven’t googled all their pictures, but I know what James Gee looks like, and 8 out of 10 have Anglo-Saxon sounding names) does not diminish a strong and informed call for diversity in the paper. From the beginning, they acknowledge that “disparities in educational outcomes did not seem to be improving” (p. 63).

As someone who has argued against token diversity in many a staffroom discussion, I was especially impressed with the way the NLG acknowledged it. I wish I had had the following quote handy when my principal called in my union rep to defend me over an alleged inappropriate remark — I was exonerated months after the meeting — when I once jokingly mentioned that the 28 (out of 29) white kids in my grade 8 class weren’t answering any questions.

“The use of diversity in tokenistic ways — by creating ethnic or other culturally differentiated commodities in order to exploit specialized niche markets or by adding festive, ethnic color to classrooms — must not paper over real conflicts of power and interest. Only by dealing authentically with them can we create out of diversity and history a new, vigorous, and equitable public realm” (p. 69).