It Takes Me Longer, Because I Read More Carefully – E-Books vs. Print Books

I was caught off guard by a Washington Post article that I read recently that indicated that students – that is, current, young, college students – have a preference for printed text over its electronic counterpart. (Rosenwald, 2015) While this seems, on the surface, sophistic, research is showing it to be true.

When we consider Raymond Kurzweil’s 1999 prognostication that, “The [print] book will enter obsolescence, although because of its long history and enormous installed base, it will linger for a couple of decades before reaching antiquity” (as quoted in Bolter, 2001), it is fascinating to note that, “the highest print readership rates are among those ages 18 to 29, and the same age group is still using public libraries in large numbers.” (Rosenwald, 2015) In her book, “Words Onscreen – The Fate of Reading in a Digital World”, Naomi Baron seeks to understand some of the rationale behind this phenomenon.

Several key reasons for students preference of print text were highlighted by Baron (2015). Students forced to study using e-texts complain about eyestrain, distractibility and poorer recall of material. From a personal perspective, I suffer all three of these e-text maladies. I have recently invested in reading glasses to both help my aging eyes and filter out some of the “blue” light of digital screens, I am among the 90% that admit to multitasking while reading online (vs the 1% of print-text readers) (Baron 2015) and I like so many others, rely partly on the “location of information simply by page and text layout — that, say, the key piece of dialogue was on that page early in the book with that one long paragraph and a smudge on the corner.” (Rosenwald, 2015) This physicality can lead to greater engagement, as one student commented, reading print books “ takes me longer because I read more carefully.” (Baron, 2015)

While e-text has made undeniable inroads into our reading space, it is not (and I would predict will never be) a total annihilation of the printed book. Pearson Education president Don Kilburn, sums up this shift, “the move to digital doesn’t look like a revolution right now. It looks like an evolution, and it’s lumpy at best.” (Baron, 2015) In fact, in a fascinating white-paper report commissioned by Ricoh in 2013, e-Book revenue accounts for only 20-30% of total profits for major publishers of all sizes.

So why, with all of the features and accessibility of electronic text, is the printed book still vastly prefered? Perhaps that reading and writing indeed has a materiality built into its nature. Chartier explains, “Whether they are in manuscript or in print, books are objects whose forms, if they cannot impose the sense of the texts that they bear, at least command the uses that can invest them and the appropriations to which they are susceptible. Works and discourses exist only when they become physical realities … This means that … keen attention should be paid to the technical, visual, and physical devices that organize the reading of writing when writing becomes a book”. (as quoted in Bolter, 2001)

Further, Baron comments that e-books, “resemble motel rooms – bland and efficient. [Print] Books are home – real, physical things you can love and cherish and make your own, till death do you part. Or till you run out of shelf space.” (Baron, 2015)

This may also speak to the anthropomorphization of books as described by Bolter (2001). Books have names and places in which they live, be it on our shelves, in boxes or in libraries. The codex also allows for a sense of closure – a beginning and end, that is diminishing in the light of the hypertextualization of electronic text.

I have no doubt that there will always be printed books, `but am curious as to how the balance will play out in the decades to come.

References:

Baron, N. (2015) Words Onscreen – The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

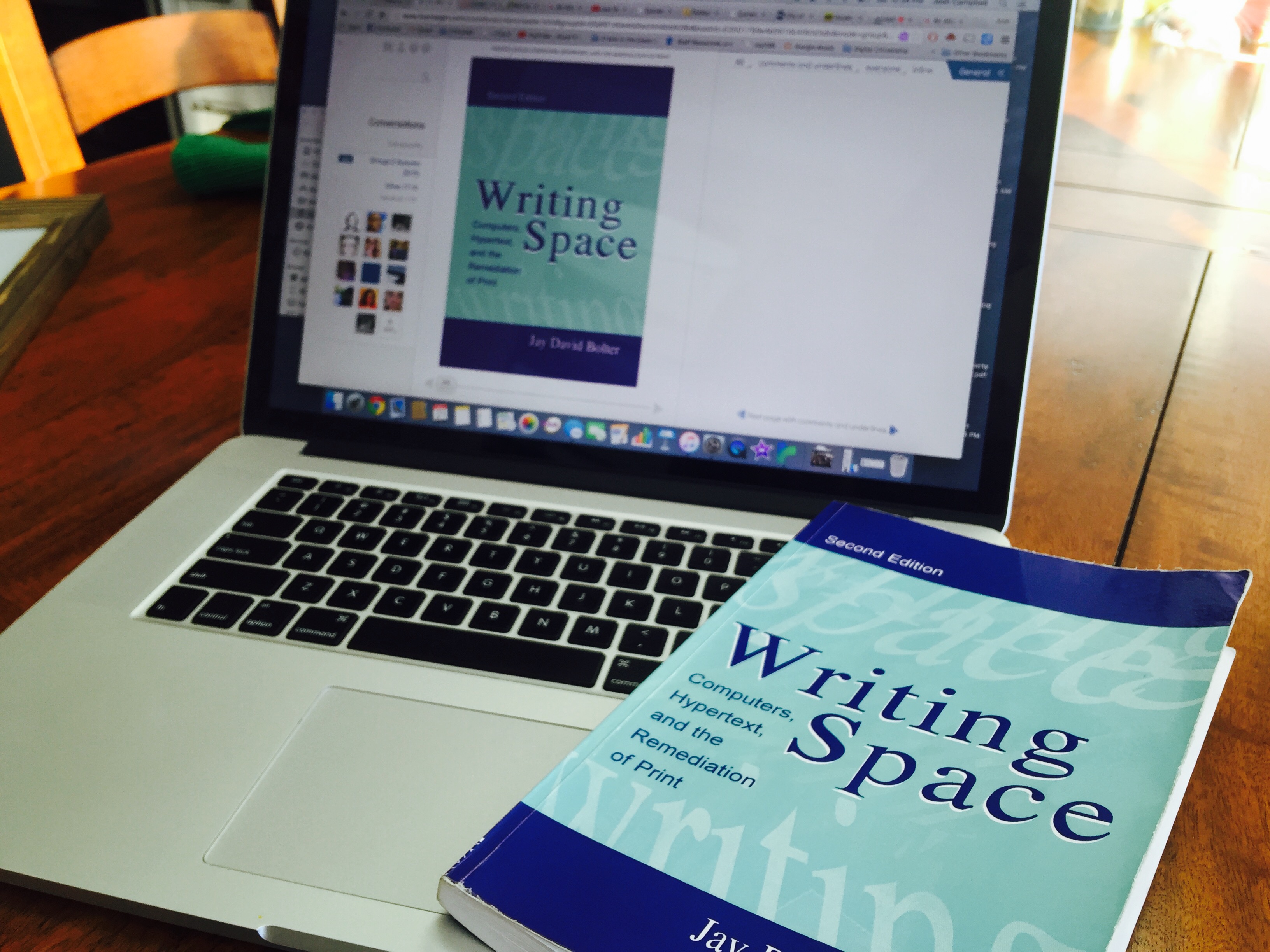

Bolter, J. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Roserwald, M. (2015, February 22) Why digital natives prefer reading in print. Yes, you read that right. Washington Post. Retreived from https://www.washingtonpost.com

Hi Joshua,

I found your post to be very interesting and insightful. I would have to say that I much prefer printed text over electronic text, especially if I’m reading educational material. Personally, when I read text online I have the desire to scan the information rather than carefully reading the text. Perhaps that is because that is how I filter through information when I am online and it has simply become a habit to keep scrolling. Therefore, with class readings, I am often having to print the articles, otherwise I don’t get a sense that I am learning the content as well as I could. I suppose it could also be argued that the layout of online text may play a role in promoting a desire to scan the pages. Unlike a book, where you physically have to turn the page, web pages (or PDFs) can seem as though they go on forever, which may encourage the urge to get to the bottom.

I agree that it will be interesting to see where the balance will be in terms of printed and electronic books in the near future.

I really liked your line ” Perhaps that reading and writing indeed has a materiality built into its nature.” There is something Etch-a-sketchish about the impermanence of text on a screen, like it’s not as valuable because it isn’t really there like words on the printed page are. I think it was Hayles and maybe Kress who mention that even the printed book comes from a digital process, but I know a couple of writers who still prefer typewriters for those same purist reasons why many of us, regardless of age, find the digital cheap somehow.

This was such an enjoyable post to read. Thank you.

Your thoughts regarding the materiality of print and Chartiers quotation (Bolter, 2001) regarding the physical realities of print resonate. The printed book is something that the reader can smooth their hand over, finger the glossy pages and when the cover is closed the intuition to hold the book close to one’s heart as the contents within steep within one’s mind, is an experience that more than one book lover can no doubt confess. In electronic form, the book becomes a part of a machine, placed within the mechanism of a tool that represents the physicality of the art rather than being the art.

As well, your post urged me to consider remediation in all of the aspects of literacy that we have explored during the duration of this course. Again reminded of Frost’s words regarding modes of literacy: “They all emerge, persist and influence each other in a continuing, timeless dynamic of the storage and transmission of knowledge. Meanwhile another pattern of technological and literary production is at work.” (2000) In spite of new productions at work, the old modes continue to remain, perhaps not in the same essence of influence, but existent just the same. I recall Ernestos Pena’s reference in our class notes to the scroll of ancient times in relation to the scrolling through the screen on our personal computers. There are other parallels that also can be thought upon: the illuminated manuscript of the medieval era and the picture book of the 20th century; the newsboys of the 19th century and the radio relaying the news; the hieroglyphics telling story for the Egyptians and the graphic comic telling story for the 21st century teen. It is fascinating how literacy changes, but also how much stays the same. From exploring the connections between the two and the influence of one upon the other through the contents of this course, my perspective of the literate world around me has forever been altered and redefined. Perhaps yours too?

oops – and references:

Bolter, J. D., (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of

print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Frost, Gary. (2000). Futureofthebook.com. Retrieved from

https://web.archive.org/web/20060511022155/http://www.futureofthebook.com

/storiestoc/scroll