Qatar is a culturally-diverse place. I mean truly culturally diverse; the kind of diversity that means “Nationals”, in this case Qataris, only make up about 12% of the population. Qatar is home to approximately 2,314,307 people of widely varying religious beliefs coexist peacefully. See for yourself (hover to explore the charts):

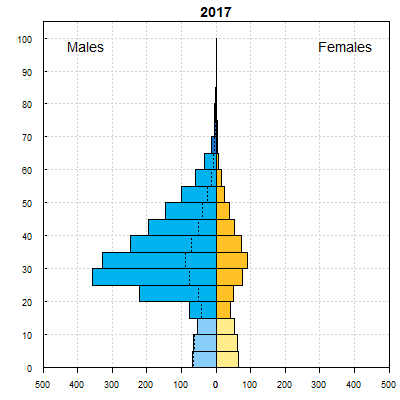

The male-to-female ratio is not well represented by either of these charts, yet I know it exists based on personal and professional experiences in Qatar. I found it well-represented by the UN’s World Population Prospects 2017:

Population is given in thousands.

Qatar has, on average, 3.41 males to a single female based on 2016 estimates. The most striking disparity lies within the 15-24 and 25-54 age groups, at 2.64 and 4.91 males to females, respectively. Being a post-secondary instructor this age group interests me, and I decided to explore how these findings may be reflected in university data. What I found truly surprised me. I’ll reproduce some charts below for context.

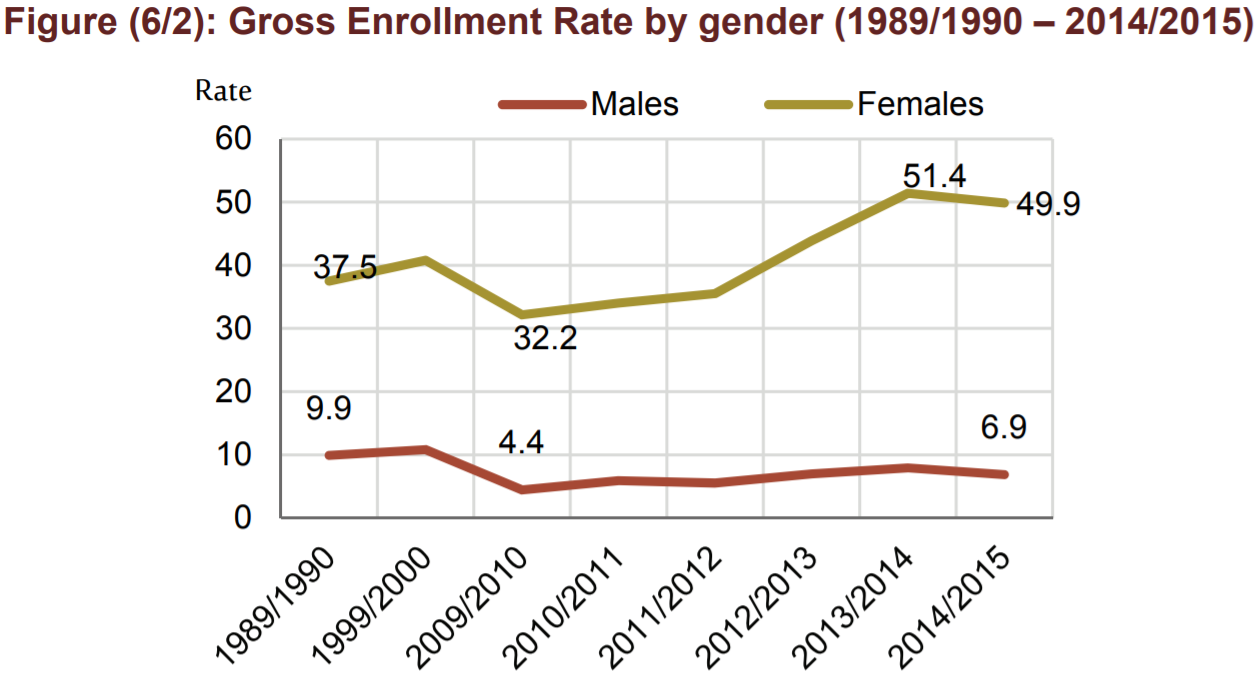

Enrollment for 2014/2015 year was approximately 28,000 students.

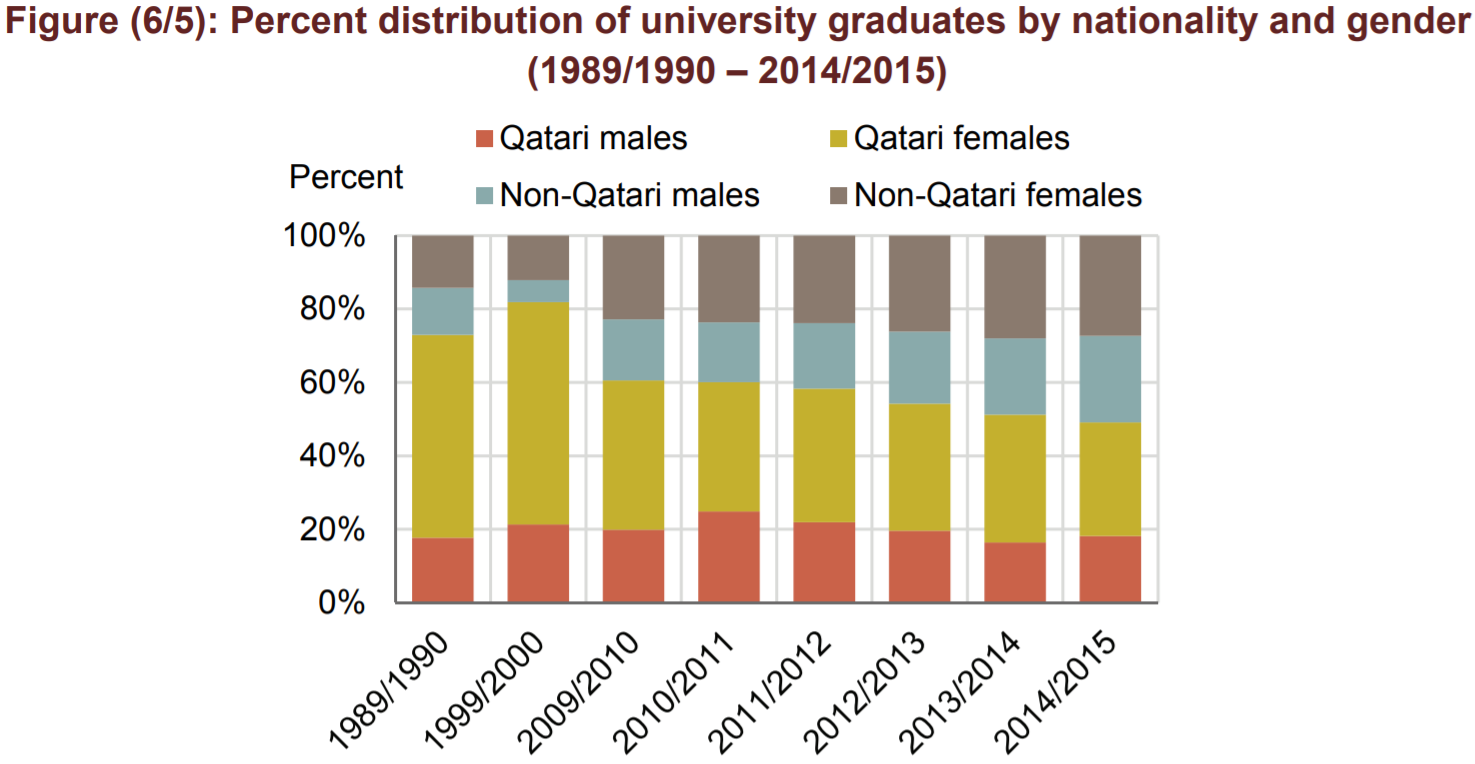

Charts reproduced from the Education in Qatar Statistical Profile 2016.

We see that while Qatari women account for a tiny fraction of the Qatari population (approx. 1.5% of the total population of Qatar is women aged 15-24, or about 80,000), they’re an undeniable focal point of the data collected.

- Comparing 2014/2015 data, their gross enrollment rate at universities far exceeds that of men – 49.9 vs. 6.9.

- More female Qataris have a post-secondary education than men when comparing proportions – 37.2% vs. 29.2%, 13.0%, and 28.1%.

- Female Qataris consistently account for the largest percentage of university graduates, both by gender and nationality, at 31%.

In short, university-level learner diversity in Qatar is completely at odds with the gender- and nationality-makeup of the country. What’s going on here?

I’ll try to unpack the situation, informed by my own informal observations of post-secondary institutions in Qatar, as well as my knowledge of the region.

Why the low Male Enrollment Rate, and Static Proportion of Male Graduates?

Sheikha Mozah, the wife of the Emir of Qatar, has lead educational initiatives since 1995, leading to the development of 16 international universities and colleges in Qatar. While this can partly explain the rise in the proportion of non-Qatari graduates, it doesn’t explain the relatively static proportion of male Qatari graduates. This, instead, can be partly explained by Qatari males joining the military upon graduating from high school. Others are often encouraged, both by their immediate families and through cultural values, to seek a western education abroad. The UK and US are popular choices. A common view is that they will acquire knowledge and bring it back to their country to help it grow and continue to prosper.

What might explain the high proportion of Female Qataris in post-secondary?

Many Qatari females are encouraged, and sometimes required, to pursue post-secondary education “at home”, within familiar Qatari culture, where it is assumed they are less likely to stray from traditional Islamic values.

Furthermore, in a culture where arranged marriages are still common, a post-secondary education can prove to be quite lucrative; not only for men but also for women. The accompanying increase in social status provides an advantage over the “competition”.

Further Reflection

One last culturally-relevant relationship I wanted to explore was one between faculty and students. Consider this final figure:

In 2014/2015, non-Qatari faculty accounted for 89% of staff (61% male, 28% female). This inspired a few questions of my own:

- Most faculty are non-Qatari men, while most students are Qatari women. Most Qatari schools have gender segregation until post-secondary. Many female students arrive to integrated classrooms and struggle with mandated group work, and it’s not uncommon for them to flat-out refuse to work with males, or vice versa. Is this really a culturally acceptable environment to impose while expecting all students to perform at their best?

- Even if women are educated at “home” in Qatar, they are usually taught by foreigners. Does this not impart its own culture? Is one to assume that instructors will not influence them?

- Parrish and Linder-VanBerschot (2010) state it is “critical that instructors … develop skills to deliver culturally sensitive and culturally adaptive instruction.” International institutions rose extremely quickly – 12 were built between 2009 and 2010 – and staffed in a hurry, with faculty often having cultural backgrounds in strong contrast to their learners. To what extent was, and is, the cultural competence of their staff assessed?

- International institutions, such as Carnegie Mellon, University of Calgary, and Northwestern University, were brought to Qatar “wholesale” to teach curriculum often unchanged from their western counterparts. Until very recently, most students hadn’t grown up engaged with, or with any experience of, western education systems. Faculty need to appreciate these cultural differences and be aware of their own cultural assumptions when dealing with common issues such as plagiarism among their students (Hayes & Introna, 2005). Are these institutions, or the State of Qatar in general, aware of the disconnect between their students’ backgrounds and their curriculum, as well as what possible impact they may be having on the cultural identity of learners?

Even with my analysis, or reflection, of the data I do not have all the answers. Perhaps no one does. I’ve learned that data on diversity, while very interesting, simply does not tell the whole story. It takes comparing and contrasting the data and exploring possible reasons for trends to make any sense of it. And, in truth, I’ve likely only scratched the surface of what could be revealed by the data. I’m very much looking forward to your own thoughts on the data, and to see yours as well!

Scott

Main Data Sources

All data collected for this assignment can be considered generally reliable. However, there are aspects of the data that make it inaccurate to some degree, especially for large data sets, such as estimations, interpolation, unavailability of public records from local government, and so on. Overall the data is considered trustworthy, as each source supported the findings of the others, with no one source contradicting another. Further detail on sources can be seen below. The “reliability” scores are my own judgments.

Data: Qatar Demographics

Author/Source: indexmundi (through CIA World Factbook)

Current as of: January 20, 2018

Reliability: 5/5

Comments: Recent, non-sensitive data collected by the CIA. US has strong ties to Qatar, so data is quite reliable.

Data: Qatar Education

Author/Source: Education in Qatar Statistical Profile 2016 – Qatar MDPS

Current as of: 2016

Reliability: 4/5

Comments: Data is directly from the Qatar Ministry but the data being a few years old.

Data: Nationality/Population

Author/Source: Priya DSouza, Priya DSouza Communications

Current as of: 2014-2017 depending on source

Reliability: 4/5

Comments: Collected independently as exact nationality breakdown is not publicly available from the Qatar Ministry.

Data: Population Estimates/Projections, Gender Data

Author/Source: World Population Prospects – United Nations

Current as of: July 1, 2018

Reliability: 5/5

Comments: Very similar data to Priya DSouza, only minor discrepancies likely due to a few years’ difference in data collection.

Data: Religions in Qatar

Author/Source: PEW Research Center Religion & Public Life Project

Current as of: 2010

Reliability: 3/5

Comments: Data is from 2010, decreasing the reliability rating.

References

Hayes, N., & Introna, L. D. (2005). Cultural values, plagiarism, and fairness: When plagiarism gets in the way of learning. Ethics & Behavior, 15(3), 213-231.

Parrish, P. & Linder-VanBerschot, J. A. (2010). Cultural dimensions of learning: Addressing the challenges of multicultural instruction. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(2), 1-19.

Nieto, C. & Zoller Booth, M. (2009). Cultural competence: Its influence on the teaching and learning of international students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 4, 406-425.