In Response to Question 2:

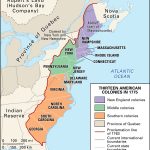

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 issued by King George III for enforcement in all of the British territories in North America. It enforced a boundary that was referred to as the proclamation line. This boundary separated the British colonies on the east coast from the ‘American Indian lands’ in the west, beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Therefore, the Royal Proclamation effectively halted the colonial invasion of the west, at least temporarily.

A map of the Proclamation Line

“We do hereby strictly forbid, on Pain of Our Displeasure, all Our loving Subjects from making any Purchases or Settlements whatever, or taking Possession of any of the Lands above reserved, without Our especial Leave and Licence for that Purpose first obtained.” -excerpt from the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The significance of The Royal Proclamation of 1763 goes far beyond the proclamation line. Often referred to as “Canada’s Indian Magna Carta”, this document served to establish and define the Crown’s relationship with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Furthermore, it became the basis for all treaty-making and continues to guide the construction of treaties in Canada today. The Royal Proclamation even informed the Canadian Confederation in 1867 and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982.

In 2013, Canada celebrated the 250th anniversary of The Royal Proclamation of 1763. However, the celebratory sentiments of this event were not shared by everyone.

“The treaty relationships and aspirations that were expressed in the Royal Proclamation are about us sharing the land, wealth and resources of this country. That has not happened” – Shawn Atleo, National Chief from the Assembly of First Nations

Some of the potentially positive aspects of the Proclamation were acknowledged by the head of Nisqa’a Nation, Mitchell Stevens, who said, “The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a foundational document in Canadian history because it affirms the government-to-government relationship between First Nations and the Crown.” Indeed, the Proclamation claimed to acknowledge the “great frauds and abuses have been committed in the purchasing lands of the Indians, to the great prejudice of our interests, and to the great dissatisfaction of the said Indians.” However, many Indigenous leaders were quick to point out the ineffectiveness and hypocrisy of the Proclamation. Danny Cresswell, Chief of the Carcross/Tagish First Nations community insisted that the Proclamation, as well as modern treaties that have been based on the Proclamation, have never truly been implemented in Canada.

“[The Proclamation] says [the Crown] can’t go in and invade their lands without some kind of a consultation or, more than that, it says they have to be compensated, dealt with, treated fairly … It wasn’t lived up to or enforced. It was nice to say…” Danny Cresswell

Therefore, while the Proclamation was instrumental in setting up relations between the government and Indigenous peoples, it is problematic in that it was never enforced properly.

Close analysis of this document provides some support for Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.

Coleman emphasizes the ‘fictive element of nation-building’ by considering the “fictive ethnicity” of British whiteness that “occupies the position of normalcy and privilege in Canada” (7). The Proclamation refers to “all Our loving Subjects” which immediately prompted thought on the ways in which this statement works to unify a massive body of fairly diverse people (all North American settlers) under one body; the British Subject. This idea of the united British Subject may have given rise to the “fictive ethnicity” of British whiteness we observe in Canada today. In the Proclamation, Indigenous peoples do not fall under the umbrella of “loving subjects”. This aligns with Coleman’s work because Indigenous people have been denied a “position of normalcy and privilege in Canada” despite being the first peoples of this land.

As well, Coleman emphasizes the necessity of forgetfulness in holding together the fictitious elements of nation-building. I was able to identify two ways in which the Proclamation potentially exemplifies this. The first is that the Proclamation itself was forgotten. It was temporary and therefore, ultimately western colonial expansion did occur. The second is that we have forgotten (or perhaps never fully acknowledged) that the Proclamation originated from the ultimate colonial power, the Crown and yet Canada continues to use it as the basis for treaties with First Nations today. Is it appropriate for modern treaties to be based on a colonial document from 257 years ago?

Therefore, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a document that carries several layers of complex significance. Its role in Canada’s history and in modern Canadian treaties is not straightforward nor is it widely agreed upon. However, it is clear that working to understand the Proclamations and its consequences in Canada (both in 1763 and today) is vital to improving Indigenous relations with the government.

Professor Karl Hele, director of First Nations Studies at Concordia University speaks to Anishnaabe students at White Pines C. & V. S. in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. (He touches upon the idea of Indigenous exclusion from being “subjects” around 2:22)

Works Cited:

“Could You Tell Us about the Royal Proclamation of 1763?” Youtube, Voices from the Gathering Place, 21 Aug. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRaATMirBQ8.

Hi Eva!

Wow, what a thorough and informative post. I really appreciate the depth of information and reflection here. I’d like to ask you though, how do you think we as individuals can encourage our government to improve Indigenous relations? What steps can we take as a collective to reach them?

Cheers,

Ari

Hi Ari,

Those are good questions! I think one way that we can encourage our government to improve Indigenous relations is through voting. We need to ensure that political parties realize that Canadians care about Indigenous relations and that we want to see them improve. I think we also have to support Indigenous voices in our smaller communities to ensure that local governments hear them.

Thanks!

Eva

Hi Eva,

That was a great summary of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. I really appreciated your insights!

It find it very interesting that the Proclamation was also used to bring French Canadians under British Canadian rule after France conceded their territory. In a way, the proclamation forced French Canadians into the unified concept of British whiteness and “loving subjects”.

On the Indigenous Foundations website (link is below), the Proclamation is referent to, not as stopping westward expansion, but as providing guidelines for the settlement of the west i.e. treaties are required, etc. The website also mentions that Indigenous people were not consulted before or during the drafting of the proclamation. Do you think that the goal of the Proclamation was to halt westward expansion or was it a temporary show of good faith that was always meant to be worked around?

Thanks,

Emily

Work Cited

“Royal Proclamation, 1763” Indigenous Foundations, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

“Royal Proclamation of 1763” Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

Hi Emily,

I think the Proclamation was, in some ways, a temporary show of good faith, as you describe. However, it did have longterm/permanent implications for westward expansion. It slowed westward expansion (only temporarily) and set up guidelines for treaties and land claims.

Overall, I think, the goal of the Proclamation was not to completely stop westward expansion, nor was it an absolute show of good faith; It seems to me that there were lots of factors that led to the Royal Proclamation and therefore, many different goals (including unifying the “loving subjects”, officially claiming eastern lands as their own, placating Indigenous groups to avoid conflict, and more).

Thanks for your contribution and insights!

Eva

Hello!

I love how in depth you went on this blog post! I chose to write on the Indian Act and through my research on that I found a big similarity in the way that even though the Act is very outdated it is still used today. I don’t know how I feel about this because I do understand history holding a lot of information and showing how far we have come as a country, but it does make me think again about if keeping Acts like this in place if it is holding us back from a better future.

Hi Megan,

I feel the same way! It is difficult to navigate a balance between respecting history and pushing for progression. And I wonder the exact same thing; by continuing to have the Indian Act/Royal Proclamation as guidelines for Indigenous relations today are we preventing our country from progressing?

Eva

Hi Eva,

I found your deep examination of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to be very informative especially how you touch on how it both holds impact on current Indigenous relations but also the promises to share the land and resources have not been upheld by the settlers. In a Canadian Politics course I have taken we discussed how acts like the Royal Proclamation and Indian Act are part of the reason that Indigenous peoples lack the abilities to protect their land rights, but that creating a substitute has also been difficult to achieve legislatively. Do you think that the same settler-colonial mentalities that created such acts is the same pressure which has prevented its change?

Hi Sophie,

That is a really interesting question! I think that it is probably likely that the same settler-colonial ideologies and anxieties that created these acts continue to enforce their necessity in Canada today. I also think that some of the lack of change can probably be attributed to hesitance to stray from tradition.

Thanks for your comment!

Eva

Hi Eva,

Thanks for your post. I had done the same question for this assignment so it was interesting to hear your take on the question. I liked your point about the fictive ethnicity that Coleman mentions, how Aboriginals are citizens but also outside regular citizens. They are never truly normalized within society, they are the ‘other’ outside the Canadian Identity. It was an interesting point as I had not consider writing about that point in relation to Coleman. The two points you made about forgetfulness in the action of nation building was different from mine. Your first point about the proclamation being forgotten as a demonstration of nation building was interesting as I said the document itself forgets the violence that produced it and that is it’s contribution to forgetfulness, the act of making such a document is the act of erasing past struggles.

The second point you’ve made was that the document was made by the British and not my Aboriginal people but we still us it as a basis for treaties today. But I think that’s less about forgetfulness. Because everyone knows, such as your sources say, that this was created without the consent of both sides. But the reason the document is used is because of the power is has as officially recognizing Aboriginal people’s rights to their lands and that they have the right to negotiate. The document in this way serves as a reminder, rather than forgetting. What do you make of my point? Would you disagree? I’d love to hear further thoughts on the nature of the document.

Nargiza