My examination of characters in Green Grass, Running Water begins on page 15 (of the ebook version), when the reader is introduced to Lionel and Norma until Joeseph Hovaugh makes his first appearance on page 25. I wanted to focus on the four elders and use of the Cherokee language in their storytelling

…

The Four Elders

Much of my examination of the four elders was informed by Jane Flick’s reading notes, however, I wanted to further expand my exploration of these characters by searching for further sources.

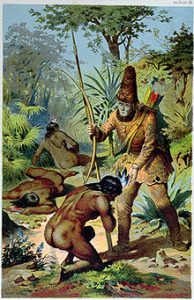

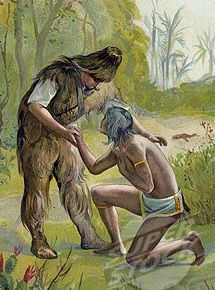

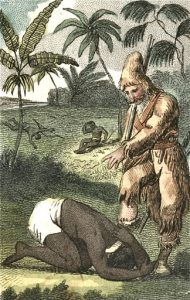

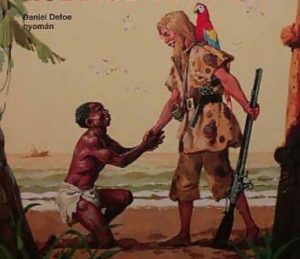

The character of Robinson Crusoe is a reference to Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719). Within the story of Crusoe’s adventure, he saves an Indigenous character who he refers to as Friday and who becomes his willing servant. Friday’s “servitude has become a symbol of imperialist oppression throughout the modern world” (Sparknotes). (Below are several artistic depictions of Crusoe and Friday).

Flicke connects the character of the Lone Ranger to “a 1933 radio serial written by Fran Striker, the 50’s television series, and numerous movies, among them: The Lone Ranger (1938), The Lone Ranger Rides Again (1939), and The Legend of the Lone Ranger (1981)” (141). More recently, in 2013, The Lone Ranger was remade. Tonto, the Ranger’s Indigenous ‘sidekick‘ was played by Johnny Depp in this version.

Hawkeye is the “adopted “Indian” name” for a character made by James Fenimore Cooper (Flicke, 141). Nathaniel Bumpoo (a.k.a Hawkeye) is a white man whose “Indian” knowledge helps him to be the hero of The Leatherstocking Saga (1826-1841). Some of the saga went on to be made into films, including The Last of the Mohicans. In these stories, Hawkeye is accompanied by Chingachgook, who is “depicted as one might imagine the stereotypical Indian — ‘nearly naked’ ‘red skin,’ a ‘scalping tuft’ with an eagle feather in it, and ‘a tomahawk and scalping-knife’ among his weapons”.

“Hawkeye” and Chinachgook as portrayed in a tv series

Ishmael is the sole survivor of the crew in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851). He too has an “Indian” companion, Queequeg who is described as “dark complexioned,” an “abominable savage,” and “a cannibal.” He is, however, entirely loyal to Ishmael, who “wakes…to find Queequeg’s arm thrown over him ‘in the most loving and affectionate manner.'” It is significant that Queequeg’s coffin is what allows Ishmael to survive, as he is able to float on it when the ship is destroyed by Moby Dick. The name Ishmael has biblical origins, but I believe that is was this the reference to Moby-Dick that King most wanted to emphasize.

I found it significant that each elder was not named directly after the “faithful Indian companion” in the narratives which they were references to (they were not named Friday, Tonto, Chingachgook, and Queequeg). They were all given the names of the white, male, protagonist in the story. By doing so, King does not make the four elders references to the stereotypical, settler-colonial idea of subservient Indigenous characters, but places them in the dominant role (the protagonist’s role). In this way, Perhaps King is working to challenge the idea of the “Indian” as a subservient, supporting-character in the story of the white man.

Cherokee Language and Storytelling

Near the end of my chosen section of this text, the four elders attempt to begin a telling story and slip into the Cherokee language. At first, the Lone Ranger tries to start with “Once upon a time”, then with “A long time ago in a faraway land” (both references to stereotypical fairytale narratives, often European in origin) and “Many moons comechucka” (a mocking reference to the stereotypical idea of how an Indigenous narrative may begin). When the others threaten to take away her turn she tries again with “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth“. Finally:

“Gha!” said the Lone Ranger. ‘Higayv:lige:i.”

“That’s better,” said Hawkeye. ‘Tsane:hlanv:hi.”

“Listen,” said Robinson Crusoe.”Hade:loho:sgi.”

‘It is beginning,” said Ishmael. “Dagvya:dhv:dv:hni.”

“It is begun well,” said the Lone Ranger. ‘Tsada:hnomdi niga:v duyughodv: o:sdv’.

Doris Mary O’Brien argues that King uses the Cree language to “make readers aware of who they are, and what they are reading. What they are reading is in part defined by the Cherokee language. Who they are is defined by their ability to recognize and make sense of what is presented to them in the text.” (42). O’Brien says that the insertion of Cherokee language into the story reminds readers to “expect a Cherokee story” (42). Ultimately, he is reminding readers that this story is not a fairy tale (Once upon a time” and “A long time ago in a faraway land”) nor is it an appropriation of Indigenous narrative (“Many moons comechucka”). He is proving the authenticity of his narrative.

Works Cited

This is genuinely helpful.馃憤 Keep up the great work!!