For the past couple of weeks my ASTU 100 class have been discussing Michael Ondaatje’s Running In The Family, a book that seems to defy the concept of genre, but I personally describe as a somewhat fictionalized memoir. A theme of the book is the concept of identity, and how it can grow and change. I began thinking of my own identity, specifically nationality, ethnicity, and religion. I began to consider if where my grandparents are from really has anything to do with my identity at all.

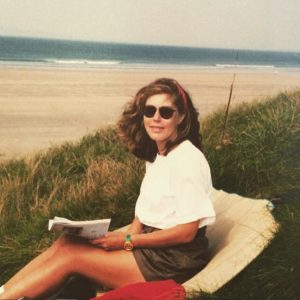

My father’s mother, Maureen, as a young woman in Northern Ireland

I worked at the Capilano Suspension Bridge Park in North Vancouver from the summer of 2015 to the summer of 2016. As one of Vancouver’s most popular tourist attractions, our guests came from every corner of the globe. This made the job very interesting; I was able to hear stories from one hundred different people from one hundred different countries in one day, even if the interactions only lasted a minute.

What made the job even more compelling was the people that I worked with. We all got along very well, so I was always comfortable asking my colleagues about themselves, often starting with “where were you born?”. Of course some were from Vancouver, but not many. The majority of people that I worked with were not only not from Vancouver, but not from Canada. I worked with people from England, Scotland, Ireland, Australia, Germany, Ukraine, Poland, Philippines, India, Korea, Laos, Spain, Iran, and many others. Many of our co-workers were also of First Nations descent. Even amongst those who were born in Vancouver like myself, no two had identical ethnic backgrounds.

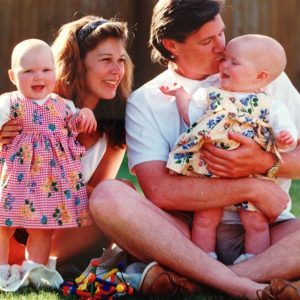

A recent photo of my mother’s parents, Leslye and Allan

This culturally diverse group is nothing new in Vancouver, which is one of the many reasons why this city is as great as it is. Vancouver’s vast multiculturalism is represented in the UBC student body. On the day I wrote this blog post I walked from a class to my dorm room with two fellow classmates, one from Thailand and one born in Uganda who lived in China for ten years.

My mother in the early 1990’s, visiting Ireland

While celebrating diversity is definitely a positive for society, it can pose some internal questionss about ones own sense of identity. I will use myself as an example. I was born and raised in North Vancouver along with my two older sisters. My father was born in Toronto to Catholic Northern Irish immigrants. He lived in Toronto only briefly as a baby before his parents decided to move to Vancouver (probably because of the weather). My very religious grandmother would go on to have four more sons, totalling five boys. Neither she or my grandfather were well educated (both never finished high school), so my father and his brothers grew up very modestly. My grandad used to see it as a source of pride when there was meat on the dinner table.

Seven years after the birth of my father, my mother was born. In South Africa, my grandpa was a university educated dentist, while my nanny (what we call my grandmother) was working as a lab technician when they met. After my mother’s oldest sister was born, they moved to Lusaka, Zambia, where their second daughter was born, as well as my mother, the youngest. They lived there for a short length of time, after which they moved to various places, including New York where my grandpa attended Columbia University to become a periodontist. My mother spent most of her childhood growing up in Hamilton, Ontario.

My parents at their wedding in 1990

Both my parents received university educations before they met. My father holds a B.A in Communications from Simon Fraser University, and my mother holds a B.Sc from the University of Guelph. They would eventually meet while working in government jobs in Toronto. My dad exceeded expectations, being the only one of his brothers to go to university. While both my mothers older sisters attended university, making her education very likely. The only expectation my mother defied was when she brought her Catholic boyfriend home to her Jewish parents.

I won’t go far into details. Basically my fathers side of the family had no issues accepting my mother, while her side of the family was more apprehensive. My grandpa even had my father meet with a rabbi to discuss the possibility of conversion (to no avail). This ultimately resulted with them eloping in Vancouver in 1990, having my (twin) sisters in 1993, and me in 1998.

There are not many “Irish” Jews in the world, so my ethnic background is definitely interesting, and something I am proud of. But being a part of two virtually unrelated cultures can make it difficult to identify with either of them. One of my friends back at the Bridge had parents who were both born and raised in Iran. She was extremely proud of her heritage, very knowledgeable about its history, and fluent in Farsi. My father’s family has been in Ireland for centuries, so there is no doubt about the location of that side of my origins. But, because of Jewish law, I am not Catholic, unlike my uncles, aunts, and cousins on my fathers side.

My parents with my older sisters, around 1994

Being Jewish is interesting, because you can identify with being Jewish without believing in the religion at all, as it is also an ethnicity. This more or less describes my mother’s side of the family, herself, my sisters, and myself. But even my secular cousins had Bar/Bat Mitzvahs, went to Hebrew School, have Hebrew names, and went to typically Jewish summer camps. There’s also the fact that they live in Toronto, which has a significantly larger and more active Jewish community compared to that of Vancouver. Added to the fact that I only have a rough idea of what countries my maternal ancestors occupied. South Africa was only home to my family for two or three generations. Before that was a mashup of countries such as Latvia, Russia, Ukraine, and other Eastern European nations where Ashkenazi Jews lived.

I pester my parents daily for answers about my background, but of course they have limits to their knowledge. Even my 92 year old grandma, with her Irish accent, does her best to tell me stories about her childhood in Belfast. I hope I will one day be able to answer more questions about where my family is from, but for now I’ll have to settle with what I have. In fact, the more I learn about my family history, the more I learn about the personalities and individual qualities of the people telling it too me. I have learned that nationality, ethnicity, and religion are not the only elements of a person’s identity, and certainly not the most important.

any women choosing not to leave their house, and some committing suicide. Many wearer’s of the chador compared the ban to feeling naked.

any women choosing not to leave their house, and some committing suicide. Many wearer’s of the chador compared the ban to feeling naked.  n a beach being forced to remove her burkini by several French police officers has gone viral. The image serves as visual metaphor for the actual issue at hand.

n a beach being forced to remove her burkini by several French police officers has gone viral. The image serves as visual metaphor for the actual issue at hand.