Life Course Analysis

For a PDF version of this chapter click here

Title Page Image 2.1

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand that there are many theories about the family.

- Acknowledge that all theories make assumptions

- Understand how life course theory examines pathways that family groups and

individuals follow through time.

- Use levels of analysis to explain the difference between individual properties such

as having a child and population phenomena such as Canada’s fertility rate.

- Acknowledge that individual agency and family life course can be modified and

changed by macroscopic forces such as war and economic depression.

<vignette>

Bette just didn’t understand. Emily had been out late again and she’d had to get the kids supper and put them to bed without Emily being around. Bette wanted to be supportive of Emily’s interest in oil painting but he thought it was becoming detrimental to their family life and unfairly affecting the workload around the house. She finally decided to confront Emily.

“I think that being at the studio every night until midnight or later is cutting into our being a family,” said Bette.

Emily looked hurt and defensive. She replied, “I am working on a painting and it will be finished soon. Then I will be home more regularly.”

Bette quickly responded, “Oh, right, until the next project. You know when we decided to have a family we took it on as a joint effort, not solo!”

Emily paused, breathed out an exasperated sigh, and then said, “That was before I became consumed by art. When I started the art courses, I didn’t know how all-consuming this would be. Finally I have found a deep passion in my life and there is no way I can give it up. I would hope you’d understand.”

With a hint of anger, Bette replied, “I wish you would stick to your commitments.”

Emily hastily shot back: “Bette, our lives take all sorts of twists and turns and marriage is about helping the other person be the kind of person they want to be, and for me, that is my art.”

“And for me,” Bette added, “that is our kids and family!”

<end of vignette>

Do people change? Certainly, in the case of Bette and Emily, that seems to be part of what has happened. But that is not the complete story. They are also experiencing changes in fairness, division of labour, time spent with their children, and expectations about the mother–child and father–child relationships. These issues are not just individual ones but involve relationships and family organization. The question we ask in this chapter is how to analyze such complex family and individual changes over time. We will argue that life course theory is the best way to analyze family and individual change, but first we must ask, What do we mean by analysis?

The Nature of Analysis

Analysis involves trying to understand a phenomenon or event by breaking it into its parts and seeing how they fit together and are organized. In doing this, we get an explanation of how something has happened. An important component of how things happen is why an event or phenomenon occurred. In general, “how” explanations tend to examine the mechanisms at work whereas “why” explanations tend to identify causes. Often these two types of explanations are the same. For example, explaining both how ocean tides work and why ocean tides work involves lunar gravitational pull on large bodies of water. In this case, there may be little difference in the two types of explanations. On the other hand, when we analyze people, we often assume that people cause themselves to do things through self-motivation. For instance, imagine that you are sitting in a classroom. How you got there and into your seat is one type of analysis, but why you are in the classroom is a matter of your motivation for formal educational training. With regards to human behaviour, motivation is often seen as the cause of behaviour or why people act as they do. So, analysis involves identifying both how and why events occur.

In the social sciences, the principal way we answer “how” and “why” questions is through theoretical analysis. Returning to our example, we might argue that the goals held by Bob and Emily have changed. We could argue that they have grown in different directions, with Bob becoming more family oriented and Emily becoming more extrafamilial because of her interest in art. Even such a simplistic analysis makes some fairly far-reaching theoretical assumptions. For example, can we conclude that people whose goals become more similar over time have happier marriages or a more equitable division of household labour? Indeed, the assumption that growing in different directions is a problem clearly depends on the issues and the situation in which a couple finds themselves. The important point here is that all analyses and all theories make theoretical assumptions in order to explain things.

Theoretical Assumptions

There are a great many ways to explain any phenomenon in the social sciences. That is, we have many theories that could compete to explain the same phenomenon. This richness of explanatory theories is one of the great strengths of the social sciences. After all, when we test competing theories, we find out which ones can predict and explain and which cannot. The richness of concepts and theories gives us alternative ways of viewing any one phenomenon.

There are too many theories about families to detail all of them here (see White & Klein, 2008). What we can do is summarize the major sets of assumptions that exist (see Box 2.1). Although various authors have detailed the general forms of social science theories (e.g., White, 2004), we will abbreviate these to just three sets of assumptions: motivational theories, normative theories, and macro-historical theories.

Motivational theories assume that you choose or determine why and how you do something. Most of us like to think that we determine our actions. If someone offers you a choice between a chocolate bar and a package of gum, you will choose whichever one brings you the greatest rewards. Indeed, rational choice theory (Coleman, 1990) and much of microeconomics (Becker, 1981) are founded on such an assumption. Critics point out that an object’s subjective worth depends on the situation and the norms in a given society. If chewing gum is viewed as perverse whereas having chocolate is perceived favourably, the value of a reward is set not by you but by society. There are other problems with a purely motivational approach, such as the argument that your choices are conditioned genetically and you are in fact determined to act in a certain way even though you may perceive choice. Finally, some notable critics argue that there is little logic in our choices since we cannot compute the costs and rewards of any action in a rational way (Tversky & Kahneman, 1988).

Box 2.1

Major Theoretical Frameworks for Studying Families

Functional theories. This school of thought maintains that the family is a normative institution in all societies and that the family is central in all societies to perform the functions of reproduction, control of sexuality, and socialization of children. It emphasizes the maintenance of functional institutions and therefore tends to see social change as a threat to society’s institutional functional relations.

Conflict theories. This framework tends to think of the family as a social group that mirrors and is affected by large-scale forces such as historical dialectical materialism (Marx & Engels, 1965/ 1865) or a clash of cultures (Huntington, 1996). It often sees family as expressing the larger forces in society, as in the argument by Straus and Donnelly (2001) that family violence is related to social and cultural values about violence such as those favourable toward guns and spanking.

Feminist theories. This complex framework encompasses many distinct schools of thought such as cultural feminism, critical race feminism, and liberal feminism. This diversity of thought is unified by the common perception that women are subjugated and oppressed by patriarchy. The family is most often seen as the central institution that reproduces the social roles and mechanisms that maintain patriarchal oppression.

Systems theories. This group of theories focuses on the notion that all elements of a system affect each other and that to understand a family system, scholars must examine it holistically. Its major concepts are feedback and equilibrium. Families have members that affect both one another and the balance of the entire family system. When the system is thrown out of equilibrium or balance, members try to correct the dysfunction by recalibrating means and goals or by changing inputs and outputs. This approach to the family has the dubious credential of having produced such concepts as the double bind hypothesis, the dysfunctional family, and the refrigerator mother. All of these have been shown to have little empirical utility for social science researchers, though a few therapists may continue to use them.

Rational choice and social exchange theories. This framework is based on individuals having the rational capacity to choose those actions deemed to produce the greatest rewards relative to costs. Over time, individuals engage in relationships such as marriage that bring, on average, more rewards than costs; as a result, these social relationships become valued exchange relationships in themselves and individuals maintain and continue them. Certainly, this microeconomic theoretical framework is one of the most popular perspectives in sociology, economics, and social psychology, in part because it strongly supports individual actors having “agency” and choice.

Symbolic interaction theories. This framework focuses on individuals being constructed by their society. Society precedes the individual. When individuals arrive in the world, they learn signs and symbols so that they can express and negotiate meanings in the social world. Some variants of symbolic interaction see the individual as being strongly determined by the existing meanings and roles in society whereas others emphasize individuals’ ability to negotiate and reorganize their social relationships. The central concept used in the study of families is social roles and how much these are socialized or negotiated. For example, when you marry, do you assume a well-determined role of husband or wife or do you negotiate the role expectations with your spouse?

Bioecological theories. This broad framework encompasses the interplay of our biological and evolutionary selves with our social selves. Early proponents focused on the concept of inclusive fitness, whereby individuals act to maximize the survival of their genes from one generation to the next. Because this process was viewed as common to our species, it failed to explain why some mothers murder their children while others are excellent parents. In the last two decades, researchers have focused on such areas as hormonal linkages between married partners, cortisol levels (stress hormones) in family interactions, and the biosocial effects of breastfeeding on a mother’s attachment to her child.

Developmental and life course theories. This framework focuses on the concepts of stages and transitions. Individuals, relationships, and families are all conceptualized as traversing stages of development. As we traverse the life course of a family or individual or relationship, significant events propel a transition to another stage. For example, a dating couple may have sexual intercourse and that may propel them to a more serious relationship. This framework is clearly concerned with multiple levels of analysis (individual, relationship, and family) and multiple determinants of transitions across time. It easily integrates many of the other theoretical approaches by using concepts and social mechanisms as they pertain to transitions and stages. Both agency and choice are included, as is social structure. It is the major theoretical framework used in this book.

For more on theories, watch this video.

<end of Box 2.1>

<continuation of text from section “Theoretical Assumptions”>

Normative theories assume that social norms predict behaviour and action. A social norm is a rule about our conduct that is held and followed by most people in a society. Because the rule is held and followed by so many people, it becomes the basis for social expectations. When we approach a stop sign, we expect people to stop because of the shared rule. Social norms are commonly divided into formal norms, such as laws or rules established by an authority such as a teacher, and informal norms, which are not codified or written down but are shared by many people. For example, your employer may formally demand that you show up at work at a certain time, but the pace and speed of work may be set by more informal norms held by the workers. Thus, two identical workplaces may have very different productivity rates because of the different informal norms about the pace of work.

Life course theory is largely a normative theory. It takes the perspective that all societies need to organize people across their life courses. The norms that organize individual and family change are related to our ages and stages of life. For example, you cannot be a lifeguard until you are at least 16 years old. This is an age-graded norm that is codified. Stage-graded norms refer to stages of life, such as the expectation (norm) that you should not have children until you are married. Thus, the stage of life (married) sets the normative expectation for having children. There are many stage-graded norms, such as finishing your education before you marry and launching your children before you retire.

The major criticism of normative theories is that they fail to explain how norms are formed and how they develop. Many rational choice theorists argue that the development of norms is dependent on the rational choices of individuals. The problem is that the norms are very different from society to society, even though we are all rational human beings. Another take on the development of norms comes from evolutionary social theory, which argues that norms are based on our biological nature. Here again, most human beings have the same biological nature but societies are very different. For example, in Korea it is the norm that people walk on the left side rather than on the right side, as is the norm in North America. Differences in norms cannot be accounted for by assuming that one group is not rational or by assuming biological differences. Nonetheless, the thorny problem of how norms arise is one that plagues normative theories and, more particularly, must be addressed by life course theorists.

Macro-historical theories assume that forces beyond the individual or society create change. These forces may be historical (Marx & Engels, 1965/ 1865) or even evolutionary (van den Berghe, 1979). This perspective argues that individuals are “blown like leaves” by the winds of historical change. In other words, our behaviour is determined neither by us nor by particular social norms but by macroscopic forces such as historical dialectics and evolution. For example, if a mother is walking between her house and her sister’s house and both houses simultaneously catch fire, which burning house will she run to first to save the children? Evolutionary theory argues that she will run to her own house to save her own children because they have more of her genetic material than her sister’s children have. Thus, her behaviour is “explained” by the general proposition that everyone seeks to maximize the reproduction of his or her own genetic material.

The major problem with macro-historical theories is explaining variation in human responses. If historical and evolutionary forces are everywhere, why is there variation between individuals, social groups, and societies? For example, some individuals are willing to give up their lives for their country but others are not. Some societies have capital punishment but others do not. Clearly, the great variation in human response to the same stimuli provides difficulties for macro-level theories. At a minimum, macro-level theories need to identify processes other than macro-level forces to explain individual variation.

These three major sets of assumptions offer very different perspectives on what causes our behaviour: individual choice, social norms, or macro-level forces (see White, 2004). Although many explanations in the social sciences can be placed in one of these three broad categories, there are specific theories that are not so easily pigeonholed. Furthermore, many students have already been exposed to theories such as symbolic interaction, exchange, developmental, and conflict (see White & Klein, 2008) and will have trouble characterizing these specific theories in such broad terms. It is important to recall that the categories we developed above refer to broad theoretical assumptions rather than to any specific theory. As we shall see, today’s life course theory has developed by borrowing aspects from each of these categories to address the particular problems that arise with theories that are dynamic or apply over time.

Life Course Theory

We introduced life course analysis in Chapter 1 (see Box 1.5 and Figure 1.4) and in the discussion of normative theories above. Thus far, the references to life course theory have been relatively unsystematic. The discussion that follows is much more detailed and systematic. The concepts and propositions we discuss in this section are essential in gaining a comprehensive and integrative understanding of your life course and the life course of families. Because this is necessarily abstract and “heady” material, you may find that some time is required to absorb the information before it all falls into place. For many of you, these ideas will become clear only when you see them applied in later chapters to topics such as dating or aging. This section is organized into three subsections. The first subsection gives a general overview of social dynamics and why we want to move toward a dynamic approach to social and family changes. The second subsection deals with four basic concepts: events, stages, transitions, and pathways. The final subsection deals with advanced concepts such as levels of analysis.

Image 2.2

Social Dynamics

As we pointed out in Chapter 1, change is everywhere. When change is slow, we perceive it as stability. When it is rapid, we perceive it as cataclysmic change. The basic question that any theory of society must address is this: How does the theory incorporate change? Change can be measured only across points in time. We know that change takes place when Family A at Time Point 2 is not the same as Family A at Time Point 1. Thus, questions of identity (same across time points) and change (different across time points) are central to developing a dynamic theory.

In Chapter 1, we raised one difficult question regarding the study of change: If everything is changing, how is it possible to have a unit to study that can be considered stable? If the Lee family has one child and then adds a second child, the family structure and interaction patterns change. How can we say that the Lee family is the same family? We resolved this problem by stating that a family exists when there is at least one intergenerational bond and this social group is recognized and governed by social norms. When the Lees have a child and there are social norms that establish relationship expectations such as nurturance and financial support, that is a family. The important point, though, is to recognize that families have histories and futures that can be analyzed. When the Lees were dating they were not a family, but their dating is part of the Lee family’s history. When both parents die and only the sibling relationships remain, that is not a family but it is part of the Lee family’s history.

This perspective on family and change further suggests that we can analyze changes over time. One issue in this regard is determining important changes and distinguishing them from less important ones. This is largely a matter of theoretical assumptions. Because we would like our analysis to be generalizable and to study the important changes experienced by the great majority of families and individuals, idiosyncratic or unique events and changes are useless. An example of such an idiosyncratic or unique event is when a person watches a boa constrictor eat a mouse and finds this a major turning point; others, however, may not be equally affected.

On the other hand, there are events that necessarily affect all families. Figure 1.4 in Chapter 1 suggested that structural changes are important to families. Returning to our example of the Lee family, when they have a second child this change in structure is accompanied by changes in relationships, such as the addition of the sibling relationship. Besides births, other structural changes include divorce or separation, leaving home, death, remarriage, and becoming a step-parent. All of these changes in structure necessitate qualitative changes in the relationships with the group. This would be equally true for a family in Greece or Singapore as it is for one in Canada.

But what if the Lee family were unusual? What if the spouses live in different countries due to work and education, and the oldest child attends residential private school in yet another country, and the new baby resides with the maternal grandparents? It may be an overstatement to say that the relationships change with the addition of the new child. Indeed, a hidden assumption in the structural approach to change is the notion that family members share a common household or domicile. Social interactions in such households would naturally affect family members. Likewise, concepts such as “separation” and “leaving home” take for granted the idea that families share a common household.

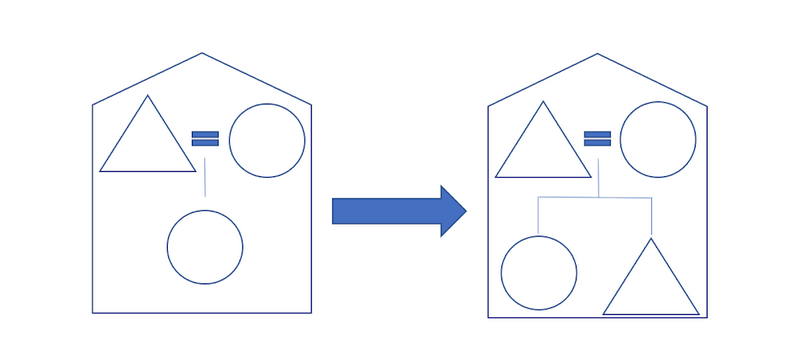

Figure 2.1 illustrates a family moving through structural transitions. This example of adding one child is not problematic. The importance of the household becomes clear as we think about an eldest child leaving home or a divorce and remarriage. Indeed, North American families may have several members living outside the household at any point in time. These diagrams will become indispensable when we discuss divorce and stepfamilies.

Figure 2.1 Family and Household: Adding a Child

<continuation of text from section “Basic Concepts”>

Basic Concepts

Events Our lives are experienced as events such as birth, graduation, wedding, and death. Our lives are measured by events but so are many other phenomena, such as diseases (onset, presentation of a symptom, fever, etc.). When someone asks you how your life has changed, you may recount events such as your father dying or your mother remarrying. These events are meaningful to people and even though they have chronological dates, it would be meaningless to say August 20, 2001, rather than, “when my father died.” The date itself does not carry the same critical information about our lives that the event does.

An event is relatively instantaneous in time. If an event has a long duration, it becomes a stage (as defined below). An event is experienced by the individual but is also a shared understanding that can be communicated to others. An event such as “a death in the family” can be readily communicated and understood by others in the same society. Certainly, there are idiosyncratic events such as, “watching the boa constrictor eat a mouse,” but these are not commonly understood as turning points in life and they would require significant effort to explain how they affected you.

One reason that most life events are readily understood is that they are “normative.” Even though we may not like to think of events such as death as normative, death is nonetheless expected and there are a host of social and cultural practices surrounding it. We may talk about premature death as shocking but overall death, like birth, is a major life event for everyone.

Stages The life course is often conceptualized as moving from one stage to another. A stage is a duration of time characterized by a particular property not present before the stage and not present after the stage. The stage during which a couple becomes new parents offers a good example. When a couple has a child, the structure of the household changes from two to three members and the couple’s interaction also changes. When the couple has a second child, the addition of a sibling relationship—with its fighting and friendship—changes the family once again. Each of these is a stage and the duration of the stage is marked by properties of interaction that are qualitatively distinct from prior stages and successive stages.

Stages are used to describe the life course of individuals, with terms such as infancy, childhood, adolescence, middle age, and so on. We can also use stages to describe small social groups such as the family or a work group. Furthermore, stages can be used to discuss the development of social organizations such as Apple and IBM. Finally, stages are often used to describe the development of nations and cultures, such as with Third World development.

The fact that stages are used with such a variety of units of analysis (individuals, groups, nations, etc.) should not disguise the common elements in these diverse analyses. Indeed, stages are characterized by three defining elements. First, all stages have a beginning point that is marked by an event. Because it marks a move from one stage to another, the event is called a transition event. Second, an ending or exit event marks the end of the duration of the stage. Third, for its duration, the stage is marked by a particular property that the stages before the transition event did not have and the stages after the exit event will not have. For example, the larval stage of most insects is marked by a lack of exoskeleton and a voracious appetite. When the insect transitions to the pupal stage, it usually has a cocoon or some form of exoskeleton for protection and will not feed as it did during the larval stage. Likewise, when a young married couple has their first child, interactions change from romantic dinners to caring for the newborn. Interactions change again with the birth of a second child, when sibling interactions supplant some of the previous parent–child interactions and add a new dimension of sibling play and conflict.

Transitions Every organism and social organization experiences transitions. In some ways, age and duration alone will account for changes. However, when those changes are described as stages, it becomes clear that events mark the transitions.

We can use the now familiar example of the transition to parenthood. The transition events of the first birth and the second birth provide markers that are relatively instantaneous transition points. Duration then becomes a characteristic of the stage and not of the transition event. As essential as this perspective of instantaneous transition points is for analysis, it may conceal the fact that many transitions have a period during which a great number of changes and adaptations occur with some rapidity. For instance, the marker of birth is accompanied by pregnancy, baby showers, prenatal classes, and other preparations for the transition to parenthood. Obviously, if the birth does not occur (as with stillborn infants), the transition to parenthood does not occur regardless of the preparation.

Transitions can be studied more or less independently of stages. We may want to study the transition to adulthood, the transition to old age, the transition to marriage, the transition to parenthood, or the transition to the empty nest. All of these transitions contain intense adjustments and, as Holmes and Rahe (1967) point out, relatively high stress loads.

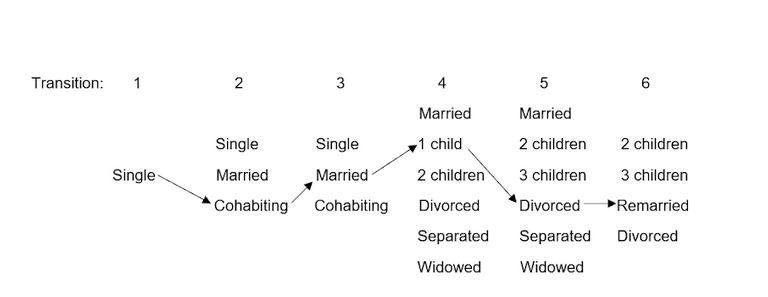

Figure 2.2 Family Stages Pathway Through Six Transitions

<continuation of text from section “Basic Concepts”>

Pathways At any point in the life course of an organism, an individual person, or a family, there is always the possibility of a stage transition. For example, a young, newlywed may experience a heart attack and die, leaving their partner alone. Though this is both improbable and unexpected, it is nonetheless possible. The life course can be conceptualized as a pathway through a maze of possibilities. Figure 2.2 shows one example through six transitions.

In Figure 2.2 we can see that there are three options for moving from the starting stage of single, never married: stay single, get married, or cohabit. If all three of these possibilities were equally likely, there would be a 1 in 3 chance for any to occur. This, however, is not the case. In Canada, about 60 percent of young people in their twenties will cohabit before they marry. For this age group, then, premarital cohabitation is more likely than marriage. The probability of a transition depends on the stage you are currently occupying, how long you have been in that stage, and the social norms favouring one type of transition over another. Someone who has been single, never married for 40 years is unlikely to get married since he or she has been exposed to the risk of marriage for a long time. On the other hand, a young couple in the early years of marriage is very likely to have a first child since most first births occur within a couple of years of marriage. The important point is that at any specific time the alternatives for transition are not equally likely.

As we think about pathways, many of us may conclude that the “cause” of transitions is really the choices we make. Certainly, rational choice theory would like to think this is so. However, do we choose for a spouse to die or choose to divorce? Many historical and incidental factors arise to change or modify our pathways. For example, wars, economic depressions, and even hurricanes may have major effects on our life course. The life course perspective acknowledges that individual choices are made but also that, for the most part, these choices are driven by the norms of the society and many other factors. For example, Indigenous peoples have choices that other Canadians do not have, associated with treaty status and “Indian” status, but these institutional statuses also constrain the choices available to Indigenous peoples by making them “different” and distinct from other Canadians. This perspective will become increasingly clear as we discuss the advanced concepts in life course analysis.

Advanced Concepts

Levels of Analysis Thus far, our discussion has wandered across diverse levels of analysis. We have discussed families, individuals, institutions, organizations, and relationships without acknowledging that we are shifting levels of analysis. This carelessness creates two problems for analyses. First, it makes it seem as if the processes of change, transitions, and stages are the same at all levels of analysis. This certainly is not the case. Second, this disjointedness makes it difficult to understand how levels of analysis influence one another. For example, institutional norms influence relationships differently when premarital cohabitation is normative rather than proscribed or viewed as deviant. As we discuss the idea of levels of analysis, both of these problems will become more apparent.

When conducting research, we may sample different units such as schools or marriages or students. The sampling unit is not the same thing as a level of analysis. A level of analysis is the theoretical and conceptual level on which we are conducting our analysis or explanation. In general, the major levels of analysis are as follows: the individual, the two-person relationship, the social group (family), and the institution (norms). The processes and stages are different for each of these, as shown in Table 2.1.

In Table 2.1 we can see that an individual may experience a need for perceptions and ideas about the world to be relatively consistent. In psychological studies these processes have variously been discussed as psychological balance and cognitive dissonance. When we transition to a two-person relationship, individuals may still want consistency but there is a new process that can occur only with two people: agreement or disagreement. Indeed, conflict is a process that begins only in two-person relationships. Once a couple has a child and becomes a family (three-person group), another new process is added. A three-person family can have coalitions of two against one, especially in democratic families. Coalitions are not possible in two-person relationships. Finally, every normative institution (e.g., family, education, work) has norms that organize our society. When most people conform to these norms, either willingly or because of coercion, the resulting stage for the institution is one in which the frequency of the behaviour is highly uniform or, to use a statistical term, leptokurtic.

Table 2.1 Levels of Analysis

| Levels of Analysis | Example of Process | Example of Stage |

| Individual | Cognitive consistency | Single |

| Relationship | Agreement | Cohabiting |

| Family | Coalitions | Married with children |

| Institution | Conformity | Norm leptokurtosis |

The stages and transitions an individual is experiencing will undoubtedly affect the relationships that person has with other people. If a person’s marital relationship is not going well, that will affect the family. Disruptions in marriage and family will affect conformity to social norms. Thus, all levels of analysis are capable of interacting. For instance, a lack of conformity in social norms about fathers in society may be experienced by the individual as a lack of clarity and an ambiguity about the breadwinner role.

Institutional Norms Every family develops its own internal norms for bedtime, hygiene, division of labour, and so on. These internal family-specific norms are idiosyncratic and are developed by the group and its organizational leadership, such as the parental figures. These internal norms, however, should not be confused with the broader society’s institutional norms. Institutional norms are those social rules agreed upon by most members of a society. Some institutional norms are codified as formal norms in legislation while others are more informal. For example, the marriage contract (licence) is a formal norm that publicly acknowledges a monogamous relationship between two adults. When a couple enters into such a contract, other legislation such as matrimonial property acts and medical acts become relevant. On the other hand, some institutional norms are informal and consensual, such as the idea that one should get married before having children. These informal norms may have informal sanctions such as shaming tied to them, but they do not have formal sanctions that the courts would enforce (as with matrimonial property acts).

It is essential that institutional norms be looked at in two very dissimilar ways (Durkheim, 1893/ 1984). On one hand, it is essential for every society to have a considerable degree of conformity to institutional norms, whether they relate to the family, politics, work, education, or religion. These norms organize and stabilize all societies. They allow us to develop expectations about the actions of others through which to predict our world. On the other hand, social change comes about mainly by normative change. For example, in the 1950s, cohabitation among the middle class was almost unknown but now it is the most popular stage before marriage. Norms that favour cohabitation rather than condemn it represent a momentous social and institutional change. This change, and most social change, begins with deviance. Not all forms of deviance are successful and become institutional in nature, but most social change is rooted in deviance at some historical point. Thus, while we all like social order, social change is also important in helping us adapt to a changing world.

Among all of the informal norms about the life course is a subset of norms that are consensual agreements about the timing of events and stages as well as the sequencing of events. For example, “one should get a driver’s licence or an education while one is a young adult,” is a timing norm or age-graded norm. On the other hand, “one should get married before having a first child,” is an example of a sequencing norm. Sequencing norms suggest the order in which one should experience stages or events. Although such statements may appear in isolation, we can see that when they appear in conjunction, much of the early life course is full of social expectations (norms). For instance, when conjoined, “don’t get married until you complete your education” and “get married before your first child” suggest that you should finish your education, then get married, and then have your first child. Although this sequence seems obvious to most North Americans, there are societies in which the norm is that a woman should first have a child to prove her fertility before she is considered “marriageable.” Conversely, in South Korea finishing education is more important for men than women, in order to secure a well-paying job before getting married. The reason for this is that upon marrying, the men are expected to provide housing for the newlyweds, which would require significant financial means (Park and Woo, 2020) The fact that these informal norms organize many of our expectations for the life course should not blind us to the fact that other ways of organizing these events and stages are possible.

Off Time and Out of Sequence The fact that social norms organize societies is important. When social norms start to break down, individuals do not know what is expected of them nor can they anticipate what others will do. Organizations do not know how to plan facilities and offer incentives to motivate workers. Indeed, when social norms break down, social expectations and an orderly society no longer exist.

The biological nature of humans means that we age. Every society must organize around the basic needs and abilities tied to infancy, adulthood, and old age. Some of these age-graded norms are formalized in laws, and informed by typical neurological development, such as those governing the drinking age or the age at which you can get a driver’s licence. Other age-graded norms are more informal, such as the age at which you should be married or the age at which you should finish your schooling. However, even the informal norms have social sanctions; for example, if you are not married by a certain age, you may be called an “old maid.” Indeed, when you are off time with the commonly agreed upon age-graded norms, there are usually sanctions or consequences, such as people saying you are “too old” for a certain task or experience.

An important complement to age-graded norms is sequencing norms. Whereas age-graded norms have expectations about how old you should be when an event is experienced (learning to drive, drinking alcohol, marriage), sequencing norms are social norms about the expected sequence of events. For instance, one sequencing norm is that you finish your education before starting a full-time job and that you get your career (job) started before you marry and that you marry before having a child.

What happens when you don’t follow these sequencing norms? Hogan (1978), and later White (1991), demonstrated that getting out of sequence early in life is associated with later life disruptions such as interrupted labour force participation and divorce. That is, once sequencing is thrown off in one area, it tends to pile up in other areas and have consequences. A straightforward example of this is teen pregnancy. When a teenager has a baby, she might take time off from school. Upon returning to school, she is with a younger cohort and her experiences of childbirth and motherhood may further separate her from her fellow students. Thus, it seems that just being out of sequence has significant ramifications for timing of labour force entry and post-secondary attendance.

It may not be obvious, but there is a strong association between being off time and being out of sequence. Since sequences are largely constructed from age-graded events or stages, being out of sequence is necessarily tied to being off time with certain events. Thus, we usually talk about being both off time and out of sequence.

Image 2.2

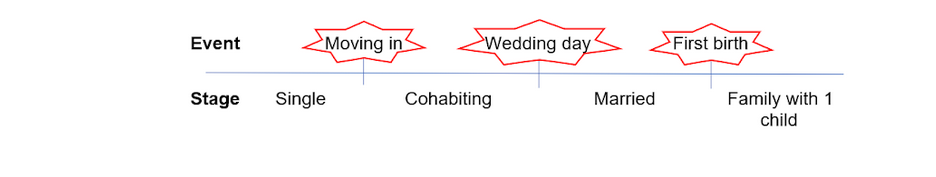

Family Stages By now you should have some idea of the intimate relationship between life events and stages of your life. Events are age graded and subject to sequencing norms. However, since a stage is defined as the period of time between two events, there is necessarily a connection between events and stages. We can see this in Figure 2.3.

The necessary connection shown in Figure 2.3 ignores an important defining element of stages: that a stage must represent a qualitatively different period of interaction or family life from the stages occurring before and after. Thus, “married” must be qualitatively distinct from both “cohabiting” and “family with one child.” There are three major ways in which life course theory deals with this qualitative dimension of stages: defining stages by family structure, defining stages by normative structure, and defining stages by developmental tasks.

Stages of family development can easily be defined as structure. Family structures are composed of the basic relationships and members we covered in our discussion of kinship (see Chapter 1). Members are designated by sex and by three relationships: inside or outside the household, affinal relationship, and consanguineous relationship. These structures are shown in Figure 2.1. The qualitative structural difference between “cohabitating” and “married” is that cohabitants live in the same household but are not married (=). The difference between “married” and “family with one child” is the addition of the child to the household and the consanguineous relationship.

In many ways, the normative definitions of stage resemble the structural definitions. With normative definitions, we identify the particular norms that are different for each stage. Thus, the norms for cohabitation, such as division of labour and power, are different from the norms for marriage, which has more defined expectations for husband and wife roles. Likewise, the norms for the parent role in a family with one child are distinct from the norms for marriage.

Figure 2.3 Stages and Events

<continuation of text>

Developmental tasks were first discussed by Havighurst (1948) and later added to life course theory by Hill and Rodgers (1964) and most recently by Aldous (1999). A developmental task is a task that must be completed or achieved before a successful transition to a subsequentstage can be made. For example, you must be able to master counting before you can master subtraction. With regards to stages, we talk about cohabitation as concerned with developing commitment, maturity in living with another person, and the ability to handle conflict within a relationship. We can talk about the developmental tasks in marriage as developing accurate communication, task coordination, and division of labour before a couple can successfully move to having a child. The idea behind developmental tasks is that if you are not successful in meeting a developmental task, then your transition to the next stage also will not be successful.

Developmental tasks may be an attractive idea to some, but the research to support the idea of developmental tasks is lacking. It can be argued that normative and structural definitions are more useful for predicting behaviour. Norms supply age-specific expectations while structure supplies the group context. Nonetheless, the idea of developmental tasks supplies a useful metaphor for this interaction of norms and structure.

Duration and Transitions Timing and sequencing norms construct expected durations for each stage before making a transition. For example, if you are engaged to be married, how long do you expect the engagement stage to last? Would six months be as appropriate as six years? If Jill gets married for the first time, how long do you think it will be before she has children? Would you expect it to be within 2 years or 20 years? As we think about timing of events, we cannot help but think about durations in each stage.

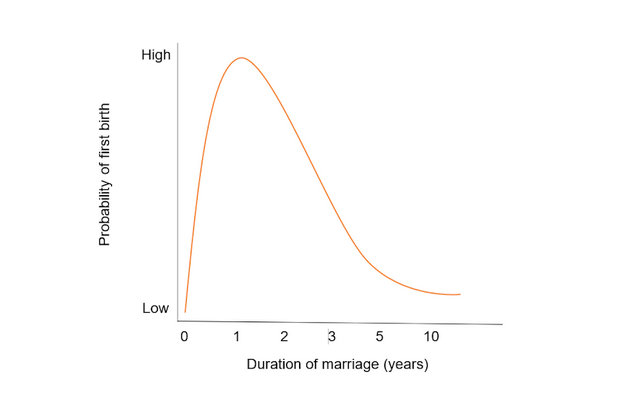

In general, the probability of a transition from one life course stage to another is a curve. Figure 2.4 graphically represents the relationship between first birth and duration of marriage. It shows that the transition from the early marriage stage to the family with one child stage is not a straight line but curvilinear. As we think about the many transitions in our lives, we find that most of our expectations have an implicit duration attached to them. This implied expectation is the result of the conjunction of age-graded timing and sequencing norms. For example, if we are dating someone seriously, there comes a time when we ask what the next step is for the relationship. We generally do not intend to be 70 years-old and still dating the same person. Instead, many of us would expect transitions to other relationship stages and to family.

Figure 2.4 Probability of First Birth and Duration of First Marriage

<continuation of text from section “Advanced Concepts”>

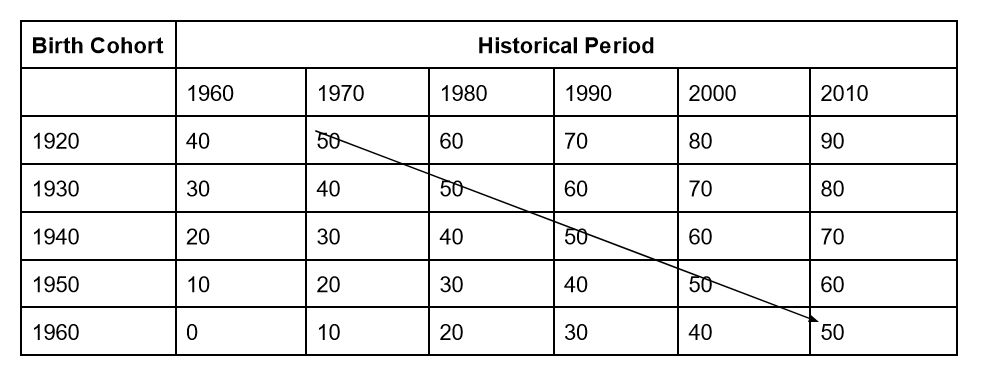

Age, Period, and Cohort Normative expectations depend on your age, the historical time period, and the birth cohort into which you were born. Age is very simply your chronological age. It is also used to suggest your maturity level and the kinds of individual stages you have experienced. For example, we do not expect a mid-life crisis for a 20-year-old but one may be more expected for a 40-year-old. The historical period in which you live is a factor in the choices and social norms that surround you. For example, living at the time of the Great Depression (1929–1938) would reduce your choices for jobs and education. Finally, the birth cohort into which you are born shares experiences and is raised with similar norms and understandings. For instance, “baby boomers,” who entered adulthood in the late 1960s and early 1970s, clearly shared common understandings and norms that make up what is commonly called the baby boom generation.

Whenever we examine life course behaviour, we have to ask if the behaviour is best predicted by one of these three factors (age, historical period, birth cohort). For example, if we assume that a mid-life crisis is determined by the age of the individual, we would not expect to find it related to birth cohort or historical period. Let’s imagine that we can measure mid-life crises in males as the time when they drive a convertible sports car while wearing a tweed golf hat. We assume that this behaviour is related only to turning a certain age, such as 40, and does not exist before or after that time. We can show what these data would look like in an age, period, and cohort matrix (Table 2.2).

The arrow in Table 2.2 represents when we expect to observe sports-car–driving males wearing tweed hats, if that is a valid measure of mid-life crisis. If this behaviour is truly determined by age alone rather than by advertising (historical period) or birth cohort norms (the tweed generation), we would expect to observe it only along this diagonal line. This matrix assists us in deriving theoretical expectations for an individual’s development (age) rather than historical events (war, depression) or social norms tied to a birth cohort. If mid-life crisis is a phenomenon seen only among 40-year-olds in the baby boom generation, we would expect to observe it only among those born in the 1950s and it would occur in the 1990s (see bolded 40 in Table 2.2). This combination of age and birth cohort was well documented in Elder’s (1974) work Children of the Great Depression, in which he demonstrated that those who experienced the Great Depression (historical period) in their youth (birth cohort) developed a lifelong concern with being frugal. Indeed, there are many places in this book where we will examine the interactions of age, birth cohort, and historical period, such as in our discussion of cohabitation and dating patterns.

Table 2.2 Age, Period, and Cohort Matrix

<continuation of text from section “Advanced Concepts”>

Other Socio-Cultural Factors It would be naive to believe that our lives and the life course of our families are determined simply by social norms about the family. Many other influences need to be considered. For instance, there are the norms for other social institutions such as work and education. If educational norms suggest that we all complete university, that normative change in education will have ramifications for starting a first job and getting married. In other words, a change in the norms and expectations for one institution (education) means that there will be consequent adaptations in the norms of other institutions (work, family). Other institutional norms need to be considered as factors of social change.

Another set of important factors influencing the life course is individual factors surrounding individual choices and the ease with which individuals can negotiate changes. There is little doubt that anticipatory socialization accounts for much of our ability to adapt to change. A child who grows up taking care of younger siblings will have socialization and experience that will make the transition to family much easier than that same transition for, say, an only child. Even babysitting and being a camp counsellor can be considered anticipatory experience for the parental role. The choices an individual makes are undoubtedly determined by macroscopic factors and by the more microscopic factors of individual values and preparation. Box 2.2 gives us an idea of how these many variables can be incorporated in research.

Box 2.2

What Does Life Course Research Look Like?

THE EFFECTS OF SINGLEHOOD AND COHABITATION ON THE TRANSITION TO PARENTHOOD IN THE NETHERLANDS

by Clara H. Mulder

University of Amsterdam

Abstract

Previous research has shown that singlehood and cohabitation are associated with postponement of parenthood. This study examines whether this association extends to the long term, potentially leading to a higher likelihood of ultimate childlessness among those with singlehood or cohabitation experience. Results from analyses of retrospective life course data from a sample of people born since 1935 and living in the Netherlands show that experience with nonmarital living arrangements has a long-term impact on the transition to parenthood. This impact is greater for females than for males and is partly caused by the higher likelihood among cohabitors to end their partnerships.

Source: Mulder (2003).

Conclusion

We have covered a lot of conceptual material in a fairly condensed form. How will we use these ideas to examine families across the life course? Certainly, all of the ideas discussed in this chapter will be useful in understanding our own and our family’s life course. However, some central concepts will prove most useful.

Stage of the life course or family stage is a central concept. Within each stage, there is maturation and development until a transition is made to the next stage. Humans in any stage of development continue to learn and change within that stage. In the language of life course theory, the individual or family adapts to the norms of the stage and meets developmental tasks so that a transition to a next stage is possible.

Transitions from one stage to another are central to the life course perspective. Most importantly, transitions can be seen as the most important events in our life course. Birth, graduation, first job, marriage, birth of children, and retirement are all significant turning points in our lives and the lives of families. A second dimension of transition is also important: the adaptation to the stresses of moving from one stage to another. Indeed, transitions represent stressful points in our lives that may become the focus of study.

Time is incredibly important in understanding change and development. Time has several dimensions regarding the life course. The duration of time spent in any one stage helps to predict transitions to another stage. We have seen that the duration of time spent within a stage changes the probability for certain transitions (see Figure 2.4) in nonlinear ways. Furthermore, time and duration can be further broken down by age, birth cohort, and historical period. Every stage we experience is affected by these dimensions of time such that the duration of time we spend in a stage is also tied to the age at which we enter the stage and the norms of the birth cohort and the historical period. In one birth cohort and historical period, a woman may be considered an “old maid” when not married by age 24; in another birth cohort and historical period, she may not transition to marriage until age 30.

At each point in the life course, you are faced with choices (agency). Your choices will certainly be determined by your values but also by how those values are “contextualized” by historical period, stages already traversed, your age, and the duration spent in the current stage. Whereas rational choice theories may emphasize your choices, life course theory sees these choices as being constrained by experience, current stage, time, and aging. Furthermore, life course theory views your values as being determined by factors such as historical period, birth cohort, and age. So while personal agency is possible, it is the social construction of choices and constraints that interests life course theorists.

At each point in the life course, you are faced with choices (agency). Your choices will certainly be determined by your values but also by how those values are “contextualized” by historical period, stages already traversed, your age, and the duration spent in the current stage. Whereas rational choice theories may emphasize your choices, life course theory sees these choices as being constrained by experience, current stage, time, and aging. Furthermore, life course theory views your values as being determined by factors such as historical period, birth cohort, and age. So while personal agency is possible, it is the social construction of choices and constraints that interests life course theorists.

This is not to say that life course analysis does not explain macroscopic historical events; it does so, but in a complex way. All social institutions have timing and sequencing norms to stay organized and keep stress levels for individuals manageable. One does not experience having a first child, marrying, finishing school, starting a first job, and buying a house all at once. Each institution has sequencing and age-graded norms. These norms, however, change over time. For example, in the 1970s, women’s labour force participation soared. To get good jobs, more women enrolled in post-secondary education programs. Marriage was delayed because these women were in school. The delay in marriage to the late twenties instead of the early twenties was a major factor in reducing fertility in Canada. This reduction in fertility created labour force shortages that can be solved only by immigration. As we look at how changes in timing in one institutional area (such as labour force and work) leads to accommodations in other institutional areas (such as marriage and family size), we see that our normative institutions are always changing and adapting to each other and to the changes in timing and sequencing norms. This is a more nuanced and subtle view of social change than the cataclysmic period effects of war and economic depression. As we shall see in later chapters, this more subtle view used in life course analysis explains some of the major trends in our society such as cohabitation, lowered fertility, and increasing immigration.

Summary of Key Points

- The social sciences attempt to answer “why” and “how” questions about social behaviour.

- “How” and “why” questions are usually addressed by theories that cite causes or the social mechanisms involved in producing a phenomenon.

- The major theoretical assumptions used to explain social behaviour are:

- Theories that cite individual motivation as a cause

- Theories that cite people following social norms as a cause

- Theories that cite macro-historical factors as a cause (economic depression, war).

- There are eight major schools of thought or theoretical frameworks used to study families (see Box 2.1).

- Life course analysis integrates many of the concepts and social mechanisms from other social science theories, including agency and social structure.

- Life course analysis examines the pathways that individuals, relationships, and families take as they transition from one stage to another.

- The level of analysis refers to any of the following units of study: the individual, a particular dyadic relationship (e.g., husband and wife, father and daughter), the family group, or the normative institution (family, education, religion, polity, etc.).

- Institutional norms that are followed by the majority of people (high conformity) show a leptokurtic pattern, whereas norms that are weak and followed by fewer people (low conformity) show a platykurtic pattern (see glossary definition of leptokurtic).

- Timing norms may be either age-graded norms (you cannot be a lifeguard until you are 16 years old) or sequencing norms (finish your education before you get married).

- Development depends on duration. This means that the length of time determining a transition is not linear but curvilinear (think about the probability of having a first child depending on how many years a couple has been married).

- Development at any level of analysis (as measured by age or duration of a unit) can be confounded with birth cohort or historical period (see Table 2.2).

- Macro-historical forces such as economic depression and war (historical period effects) will always affect life course trajectories. At the same time, institutional changes in timing and sequencing norms and cross-institutional accommodations explain any social change in our world.

Glossary

age-graded norm A social norm that refers to the age or timing of a particular event or stage. When people say, “Oh, you’re too old for that,” they are expressing an age-graded norm expectation. See also timing norm.

anticipatory socialization This refers to training, skill acquisition, and knowledge gathered for a future anticipated social role such as spouse or parent.

developmental tasks Tasks that are expected in a given stage. The successful transition to a subsequent stage depends on the completion of these tasks. For example, newlyweds should learn to coordinate tasks before they become parents.

expectations Social expectations are a corollary to social norms. If we have social rules about behaviour, we can form expectations about how people will behave. For example, when we get on a bus, we expect the driver to ask for some form of ticket or payment.

event Any occurrence or experience that can be pinpointed to a relatively instantaneous time. For example, pregnancy is a stage or period of time, but finding out one is pregnant is an event.

evolution Any process determined by a consistent set of rules or principles that explain and predict the continuity of change. For example, Darwinian evolution predicts change as a result of natural selection.

formal norms Social rules that are codified or written down in legislation or institutional documents such as contracts.

historical dialectics A dialectical process moves from thesis to antithesis to synthesis. Historical dialectics is the interpretation of historical events as representing thesis ➛ antithesis ➛ synthesis. The most cited examples of this are the works of Marx and Hegel.

informal norms Social rules shared by people in a society but not written down as laws or contracts. For example, the expectation that students study is an informal norm. Schools, however, only measure and record test scores.

leptokurtic This term refers to a type of frequency distribution in which all cases tend toward the central values. Therefore, this type of distribution suggests high conformity of behaviour. This can be compared to a platykurtic distribution, which is spread out and suggests less behavioural conformity.

off time On time and off time refer to whether your age at an event or the duration in a stage matches the age or duration expectation. For example, the expectation is that you will be in your late twenties or early thirties when you have your first child.

rational choice theory This theory proposes that individuals choose events, people, and things based on the principle of maximum profit (rewards versus costs). Some rational choice theories, such as those of Coleman (1990), derive social norms and social organizations from the individual’s profit-seeking calculations and behaviour.

sequencing norms Norms about the expected sequence or order of life events (normative pathway).

social norms Norms or social rules followed by most people in a group (frequency) and that are sufficiently common as to be expected (social psychological).

stage A duration of time characterized by a particular property or form of interaction or structure that is qualitatively different from that found in the preceding stage and not present in the subsequent stage.

transition event An event that is considered relatively instantaneous in time and that divides the previous stage from the next stage in a life course.

timing norm A norm that suggests at what age you are expected to experience a stage or event. See also age-graded norm.

Connections (Links)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_course_approach

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holmes_and_Rahe_stress_scale

http://ezinearticles.com/?Negotiating-Difficult-Life-Transitions&id=9419

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/learning_history/children_depression/depression_children_menu.cfm

End of Chapter Multiple Choice Practice:

End of Chapter Short Answer Practice: