Cohabitation

For a PDF version of this chapter click here

Title Image 4.1

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the recent historical development of both the rise and the prevalence

of cohabitation.

- Develop an awareness of the international differences in the practice of cohabitation to better appreciate the diverse social influences that affect cohabitation patterns and outcomes.

- Understand the legislative influences affecting union formation patterns from one national context to another.

- Discuss the key variables associated with cohabitation research as well as the major typologies used to understand cohabitation in relation to other union statuses.

- Discuss the effects of cohabitation on later relationship stability and child outcomes, and the effects when cohabitation is practised among the elderly.

<vignette>

The small neighbourhood restaurant was unusually busy for a Monday evening, but this was Valentine’s Day and virtually every table was occupied by a couple. Mary and John were out for a romantic dinner to celebrate the three-month anniversary of their relationship. As the couple ate their meal, John’s mind was on popping the question: Should we move in together? Mary’s thoughts were slightly different. She was wondering if John was the type of man who could commit to a long-term, meaningful relationship and care for her daughter.

At the next table, another couple was talking about whether they really wanted to spend a lot of money on a wedding or use that money to buy new furniture and make their condominium look more inviting. Meanwhile, the table in the corner was occupied by a sad-looking couple. Their conversation revolved around their relationship as well. They had been living together for more than a year yet they kept coming back to the same nagging question: How did this happen? How did we end up living together without a plan of where the relationship was going to go next?

Harriet and Marv, an older couple, were discussing their banking excursion earlier that day. They talked about how much easier things would be if they had joint accounts and didn’t have to placate their 50-year-old children. They would have married if they hadn’t gotten so much flak about inheritance complications. Harriet and Marv both lost their lifelong spouses more than a decade ago and live comfortably together, yet for the sake of the children they keep their substantial assets separate.

<end of vignette>

Late adolescence and early adulthood bring increased responsibilities and opportunities. Most often, the two are connected. One of the most anticipated desires and yet a feared opportunity at this stage of life is forming an intimate relationship outside your kinship structure. Early crushes turn into first dates, then progress to going steady, and eventually lead to a completely new realm of physical and emotional experiences and feelings. Since most individuals find these new feelings enjoyable, there is a desire to increase their frequency or at least create a more stable environment in which these experiences can continue. Historically, marriage was the next step, but this is not so in the twenty-first century. The rise of non-marital cohabitation is one of the most important recent trends in the study of the life course of the family. The combination of earlier and important life course decisions being made in late adolescence and early adulthood creates outcomes that often guide a person’s pathway for the rest of his or her life (Barber, Axinn, & Thornton, 2002). As acceptance of and participation in nonmarital cohabitation continue to rise, changes in cohorts will also continue. The type of person who cohabited and the reason for cohabiting in the 1960s are quite different from those of the cohorts in the twenty-first century. Of particular interest to researchers is the influence that various types of union formation patterns will have on later outcomes such as relationship stability, financial solvency, and child adjustment.

This chapter explores cohabitation across the life course. It begins by setting the historical context needed to understand the importance of the rise in cohabitation. This is followed by a cross-national comparison of cohabitation patterns. Next, we explore the varied approaches to cohabiting, especially in relation to marriage. For example, will the prevalence of cohabitation establish it as a new life stage leading to marriage? What differences might social stratification and ethnic variability have on cohabitation patterns? This section also includes a focus on the controversial issues of commitment differences between cohabiting and married couples as well as cohabitation’s impact on later relationship stability. Next, a section is dedicated to the changing legal landscape surrounding the increased prevalence of cohabitation, addressing issues such as child custody and personal property. Finally, we address the growing trend of cohabitation among older adults.

The Rise in Non-Marital Cohabitation

Over the past 40 years, cohabitation has moved from being viewed as a deviant form of union formation to the preferred social norm that precedes marriage, acting for many as a trial marriage. The dramatic change in the number of cohabitors over just a few decades bears this out. About 10 percent of marriages between 1965 and 1974 included cohabitation as a transition state. By the early 1990s, 55 percent of U.S. marriages were preceded by cohabitation (Bumpass & Lu, 2000). According to Pew Research Centre in the United States marriage is trending down while cohabitation is going up. In 2018, 53% of U.S. adults ages 18 and older are married, down from 58% in 1995. Over the same period, the share of Americans who are cohabitating has risen from 3% to 7%. Internationally, the developed world shows an even greater adoption of cohabitation. For example, by 2017, 81% percent of married couples in Australia cohabit before marriage (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018). In Norway, approximately 80 percent of individuals cohabit before their first marriage (Wiik, 2008). At the turn of the twenty-first century, Canada mirrored France, New Zealand, Mexico, and Finland with approximately 16 to 18 percent of all unions taking the form of non-marital cohabitation. Cohabitation continues its upward trend in Canada. In 2001, 16.4% of all couples were living together, increasing to 21% by 2016. Quebec has the highest rates of cohabiting couples, at 31.5%. A concern for cohabitation research has been the heterogeneity of cohabiting couples. Union formation pathways are diverging from historical normative patterns and the question is whether the life course is becoming too de-standardized to be of empirical value. Previous research pointing to the diverse and disordered nature of family-related transitions gives some support to these concerns (Hogan & Astone, 1986). This rise in divergent life course pathways involving cohabitation has led to increased research on the impact that premarital cohabitation has on later marital stability.

Cohabitation in Context

Historical Context

Intimate union formation has been the centrepiece of human behaviour over time. Without some form of intimacy, humanity would not reproduce itself. Customs, patterns, and traditions regarding union formation have varied over time and across cultures. For most of the last two millennia, Western civilization has given preference to monogamous, heterosexual relationships legitimized by religious edicts or state laws in the form of marriage. The social customs surrounding marriage—the arranging of marriage partners, traditions surrounding the ceremony, who pays, what people wear, how long the wedding ceremony lasts, what the couple do and where they live after the wedding—are just a taste of the myriad wedding variables. In light of this diverse yet enduring social pattern the events over the past 50 years gain significance.

The latter half of the twentieth century has seen a variety of prominent social changes that have affected the pattern and sequence of an individual’s life events. The rise in the prevalence and acceptance of non-marital cohabitation is one such change. How millennia of tradition can be reversed in just a few decades is the type of social phenomenon that social scientists find fascinating research material. Historically, marriage as a significant life event has gained privileged status over other forms of union formation. Thornton, Axinn, and Xie (2007) link the change in the establishment of unions with other social institutional changes that have affected the life course, such as changes in labour markets, educational norms, and welfare state policies. The secularization of society, the feminist movement, availability of reliable birth control, the sexual revolution, female labour force participation, and the rapid rise in the divorce rate have all been cited as additional factors connected to the change in union formation patterns over the life course.

Image 4.1

Historically, marriage is an institution that formed out of economic necessity. Men and women have always been attracted to each other, but attraction alone has seldom provided a solid rationale for establishing a permanent relationship. In contrast to the highly sensual and emotional appeal that often characterizes the modern idea of marriage, survival and function have driven most people to marry. Women relied on men to provide protection and provisions for themselves and their children, while men relied on women for child care and meal preparation. Both men and women relied on children as economic assets who could provide additional labour to meet household needs. Today, in most of Western culture, women no longer need men to provide for them or to protect them and their children, and men no longer see the need for women as economic partners. Children are viewed as economic liabilities and—because of longer life expectancy and greatly reduced infant mortality—few children are born. The Industrial Revolution ushered in the daily geographic segregation of the family as an economic unit by removing the father from the household while the mother adapted to an ever-growing middle-class lifestyle focused on domestic responsibilities. The Industrial Revolution cracked and eventually broke the economic dependency that men and women had with marriage.

Further individuation of family structures led to the decline of marriage as a marker of one’s transition to adulthood. Social norms regarding sexuality began to adjust to the rapidly changing culture created by changes such as universal education for children and adolescents, not to mention technological changes such as the automobile, the telephone, and eventually the internet and cellphones.

Technological Context

What the automobile was in the 1920s, the cellphone may be in the 2010s. The automobile played an important part in changing the way young people courted one another. No longer was sitting in the parlour with a parental chaperone the only way for a potential suitor to spend time with his object of interest. The automobile provided freedom and autonomy from watchful guardians. Peter Ling (1989) argues that the “devil’s wagon” and “brothel on wheels” shouldn’t get all of the credit for planting the seeds of the sexual revolution since it was only “one of the changes in social and group relationships that made easier the pursuit of carnal desire” (p. 18). In addition to social media sites, the introduction of low-cost cellphones marketed to children has provided greater autonomy and freedom from parental monitoring almost 100 years after the automobile was introduced. This freedom has implications, however (see Box 4.1). There was a time when each household had one phone attached to the wall by a cord. Everyone knew which family member was called and who was on the other end. Today, with individual phones capable of text and video messaging, the ability to send sexual content directly to another person has created an entirely new level of personal communication. Sexting is the term used to describe text messaging of sexual content via cellphones and is growing in prevalence (see Box 4.2).

| Box 4.1 |

| Reiss’s Theory of Autonomy |

| There is presumptive evidence for assuming a general tension between a courtship sub-culture which furthers a high emphasis on the rewards of sexuality and a family sub-culture which stresses the risks of sexuality. . . . If youth culture stresses the rewards of sexuality, then to the extent young people are free from the constraints of the family and other adult type institutions, they will be able to develop their own emphasis on sexuality. The physical and psychic pleasures connected to human sexuality are rewards basically to the participants and not to their parents. . . . Thus, the autonomy of young people is the key variable in determining how sexually permissive one will be (Reiss & Miller, 1979).

Source: Ishwaran (1983, p. 137). |

| Box 4.2 |

| Sexting |

| Today, many teens seem to engage in “sexting.” One survey, conducted on behalf of both CosmoGirl.com and the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, found that 20 percent of the 653 teenagers surveyed had engaged in sexting.

Source: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (2008). At least one in four teens are receiving sexually explicit texts and emails, and at least one in seven are sending texts (Madigan et al., 2018). More than one in 10 teens are forwarding these sexts without consent, and approximately 1 in 12 teens have had sexts they sent shared without permission. Source: Prevalence of Multiple Forms of Sexting Behavior Among Youth A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (Sheri Madigan, Anh Ly, Christina L. Rash et al., 2018) |

Technological advancements, including easy access to reliable birth control, greatly influenced the dating and sexual patterns of young adults. All of this newfound independence and freedom facilitated greater sexual exploration and expression outside adult supervision. Thornton et al. (2007) see this trend as contributing to the rise of sexuality as a recreational activity in contrast to an activity within a relationship. Easier access to consenting sexual partners combined with the decline in social stigma for those sexually active outside of marriage appealed to some but not others. Conservative social groups decried the new liberal attitudes toward sexual expression. Even some feminists generally supportive of the sexual revolution saw this trend toward sexual freedom as removing some of the influence that women had over men to commit to marriage. With ample willing partners available and little perceived social cost to being sexually active, why engage in marriage just for sex?

The National Marriage Project at Rutgers University in New Jersey (Whitehead & Popeno, 2000) conducted a study of twenty-something males and females regarding their views on and experiences with dating and mating. This study is interesting for a variety of reasons, but one important reason is that it relied on a sample of non-college-educated young adults, a group often neglected in social research because of the ease of accessing college-educated respondents. The young men and women in this study indicated that marriage was a desirable goal and that they expected marriage to last for a lifetime. Unfortunately, the goal of finding one’s soulmate was viewed with skepticism, especially by the females. This group represents a generation jaded by divorce and lack of committed relationship templates in their lives. The National Marriage Project found that this group of young people was not interested in marriage during their twenties, nor did they see their twenties as a time to focus on romantic relationships. Instead, as labelled by the researchers, it was a time for sex without strings and relationships without rings. The word love was seldom used by the respondents. Instead, the focus was on sex and relationships, the distinction being that the latter requires some level of commitment and investment of time and money. Sex, on the other hand, is fun and requires no ethical obligation other than mutual consent. Males and females agreed that in casual sexual encounters, people will lie about their sexual histories. The best advice for those looking for casual sexual hookups is to “trust no one.” The club scene is a frequent destination of young, working twenty-somethings, but not to find a mate. Clubs are viewed as a place to drink, have fun, and look for casual sexual hookups. One young male put it bluntly when he referred to the calibre of females he thinks frequent clubs: “Club girls are trash.” Females have just as low an opinion of the male club clientele, who they describe as liars who are only looking for sex. The option for a regular sexual partner without the commitment connected to marriage made cohabitation a nice fit for this cohort.

The rapid change in norms and values surrounding non-marital sexuality and the resultant rise in cohabitation led to a serious generation gap between cohabitation’s early adherents and their parents. That gap may be diminishing, as current cohorts of parents grew up in a time when cohabitation and sexual freedom were more normative than when their parents grew up.

International Context

Cohabitation patterns have been shown to be highly influenced by contextual factors. Early research almost universally showed negative consequences in regards to later marital stability. As cohabitation becomes more normative, that connection has become less consistent. Teachman (2003) and Smock (2000) found little or no negative impact of cohabitation on later marital stability. Research in Australia (De Vaus, Qu, & Weston, 2005) and Canada (White, 1987) show support for positive marital stability. These divergent findings reflect not only the moving target that is both marriage and cohabitation but also the varied context in which union formation patterns take place. Not only is there diversity among nationalities regarding union formation patterns and later outcomes, there are variations among nations as well. Canada provides an excellent example of the cultural context regarding the study of cohabitation. Canada is officially a multicultural country with a general tolerance for diverse ethnic traditions and customs. The most distinct cultural differences are found between the two charter language peoples: the French and the English. The province of Quebec has a distinct culture and language as well as distinct attitudes and behaviours regarding cohabitation. Cohabitation is much more socially acceptable in Quebec and as a result is more prevalent there than in other parts of Canada. That prevalence translates into cohabiting unions that last longer and are more likely to have children present, with 63% of children being born to unmarried parents in 2009, as compared to 4% in 1960 (Lardoux & Pelletier, 2012). Quebec tends to resemble some of the European countries in this regard rather than the rest of Canada and North America.

| Box 4.3 |

| The Deinstitutionalization of Marriage |

| Andrew Cherlin on marriage, cohabitation, and societal trends in family formation |

International differences in cohabitation practices also reflect this diversity. Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) and Liefbroer and Dourleijn (2006) studied cohabitation from a comparative perspective. Both sets of authors make arguments regarding the normativeness of cohabitation affecting a variety of family transitional events such as fertility, stability, and formation patterns.

Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) see the increase in fertility among cohabiting couples as a major contributor to the general interest in the topic. Non-marital cohabitation has existed through time, but the connection of births to unmarried mothers has attracted the attention of the public. They cite Ventura and Bachrach (2000) to indicate that non-marital births have grown from 4 percent in 1950 to 33 percent in 1999. Research has consistently pointed to the statistically significant negative effects on children who grow up in single-parent households. The place of fertility in the study of cohabitation is important. The more cohabitation is accompanied by fertility, the more it will resemble and compete with marriage as a preferred form of family union.

Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) use fertility patterns to establish six typologies of cohabitation (listed later in Table 4.5) that examine the social context of the acceptance of cohabitation alongside the empirical indicators and predicted outcomes on the participating adults and affected children when present. Their findings show clusters among the 17 included nations. Countries with a low incidence of cohabitation included Italy, Poland, and Spain. Belgium, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Switzerland were clustered in the prelude to marriage typology. This group is characterized by a higher incidence of cohabitations that last for a shorter time, end in marriage, and precede the birth of children. The countries grouped together in the stage of the marriage process treat cohabitation as a transition stage that tends to last longer. This group is more likely to have children in the union, but marriage follows shortly after their birth. This cluster included Austria, Finland, Germany, Latvia, and Slovenia. The United States and New Zealand represent the alternative to being single typology characterized by cohabiting unions that are brief, non-reproductive, and end in separation rather than marriage. The alternative to marriage typology is defined by cohabitating couples who remain in their relationships for longer periods, are less likely to get married, and expose children to the cohabiting union for longer periods. This cluster contained Canada and France. The last typology had Sweden alone and is described as indistinguishable from marriage. This final group is similar to the alternative to marriage group in that there is a higher incidence of cohabitation lasting for longer periods. Children are frequently exposed to their parents’ cohabitation in this group but for a shorter time, because parents do not view cohabitation as an alternative to marriage and are ambivalent about the difference. Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) see these couples as entering marriage for pragmatic reasons rather than avoiding it on principle.

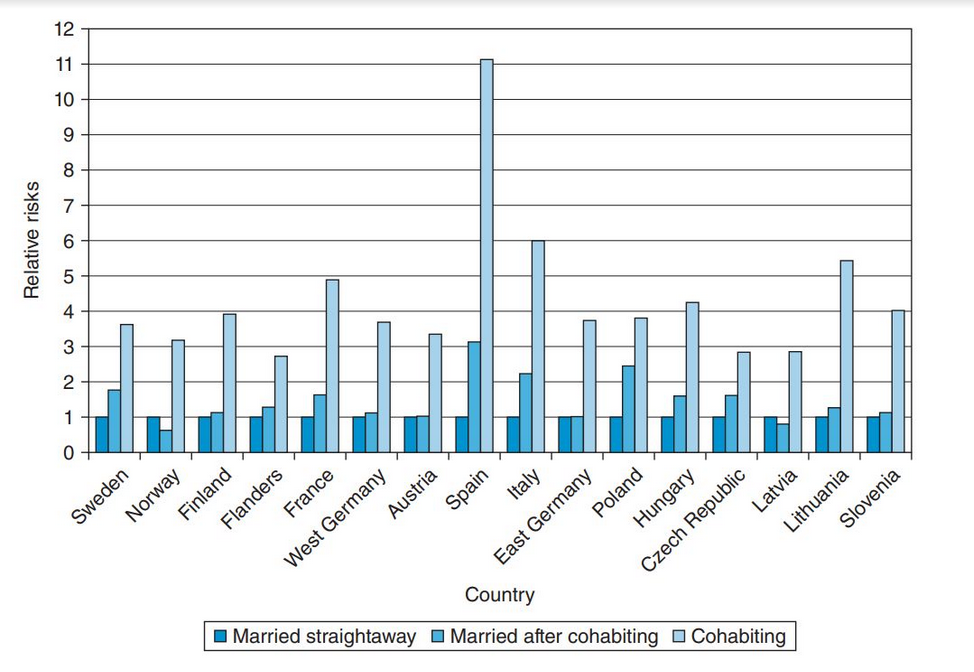

Figure 4.1 Relative Risk of Union Dissolution for Women in Different Types of Union, by Country

Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) make some important summary points regarding the regional findings of their research. They note that the three non-European countries in the study—Canada, New Zealand, and the United States—were difficult to categorize because of the heterogeneity of the population. Canada has two official languages and all three countries are ethnically diverse. The authors caution against making overgeneralizations about these populations’ cohabiting patterns. What should be taken from these findings is the importance of contextual factors that influence the union formation patterns of adults across the life course and the diverse ways in which children are influenced as a result.

The second important cross-cultural study on cohabitation also focuses on the local context’s impact on union formation patterns. Liefbroer and Dourleijn (2006) studied 16 European nations in their research on the role of diffusion in explaining the differentiating patterns of marital stability outcomes for those who previously have cohabited. Figure 4.1 shows the relative risk of union dissolution for women married with prior cohabitation and women cohabiting outside of marriage compared to women going straight to marriage. Values above 1 indicate a higher risk of dissolution compared to women who go straight to marriage, while values below 1 imply lower risks.

| Table 4.1 Cohabitors as a Percentage of All Couples | |||||

| 1990s | 2000s | % Change | |||

| Australia | 1996 | 10.1 | 2006 | 15.0 | 48.5 |

| Canada | 1995 | 13.9 | 2006 | 18.4 | 32.4 |

| Denmark | 1995 | 24.7 | 2006 | 24.4 | -1.2 |

| France | 1995 | 13.6 | 2001 | 17.2 | 26.5 |

| Germany | 1995 | 8.2 | 2005 | 11.2 | 36.6 |

| Italy | 1995 | 3.1 | 2003 | 3.8 | 22.6 |

| Netherlands | 1995 | 13.1 | 2004 | 13.3 | 1.5 |

| New Zealand | 1996 | 14.9 | 2006 | 23.7 | 59.1 |

| Norway | 2001 | 20.3 | 2007 | 21.8 | 7.4 |

| Spain | 2002 | 2.7 | NA | ||

| Sweden | 1995 | 23.0 | 2007 | 28.4 | 23.5 |

| United Kingdom | 1995 | 10.1 | 2004 | 15.4 | 52.5 |

| U.S. | 1995 | 5.1 | 2005 | 7.6 | 49.0 |

France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Spain generated from United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), Statistical Database, Gender Statistics (http://w3.uncce.org/pxweb/Dialog/Default.asp).

Australia: Statistics Australia Census Tables, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cat. No. 2914 (2006) and No. 4102 (1996).

Canada: Statistics Canada 2007, Legal Marital Status, Common-law Status, Age Groups & Sex.

Denmark: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (1995) & Statistics Denmark (2006).

New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand, Census of Families and Households & 2006 Table Builder, Marital Status.

Norway: Statistics Norway, Population & Historical Census, Table 24 and Statistical Data Bank.

Sweden: For 1995, all couples from United Nations Economic Commission for Europe data less married women from Statistics Sweden. For 2005, Population Table 28 and Statistics Sweden Statistical Database.

Great Britain: Focus on Families & Focus on Families National Statistics.

United States: America’s Families and Living Arrangements, 1995 & 2005 (rate is based on self-identified unmarried cohabitors not POSSLQ (Persons of the Opposite Sex Sharing Living Quarters).

Source: Popenoe (2009, p. 431).

The results indicate that women in cohabiting relationships are much more likely

to face a union breakup than women who married right away. Most countries show a

risk of 3 to 4 times that of the risk for those who marry right away, with Spain showing

an increased risk of 11 times. Those who cohabit prior to marriage fare much better. In

some cases, the data indicate that an improvement in risk is created after cohabiting, as

in Norway. For half of the countries, no statistical difference in risk was seen between those who went straight to marriage and those who cohabited before marriage. As in the previous cross-cultural study, this research focused on the role of changing norms regarding the social acceptance of cohabitation as a stage of marriage or a marriage alternative. Diffusion as an explanation for national differences of subsequent negative marital outcomes for cohabitors is based on the idea that innovation is usually adopted among a smaller group before spreading to the general population (Jaakkola, Aromaa, & Cantell, 1984). Schoen’s (1992) test on cohort data in the United States supports the hypothesis that as cohabitation becomes more common (see Table 4.1), the distinctions between those who cohabit before marriage and those who do not will diminish.

Liefbroer and Dourleijn (2006) present the argument that, with diffusion, you will have both early adopters and late adopters (or “laggards”), with the general population fitting between these extremes. In the area of cohabitation studies, religiosity has been identified as a barrier to acceptance and participation in cohabitation. This is illustrative of those labelled as late adopters. The authors use this line of reasoning to show that the selection hypothesis (people with fewer relationship skills or less relationship commitment tend to be more likely to cohabit) explains later marital instability. Marital instability will be most prevalent when cohabitation occurs in a social context in which just earlier adopters or late adopters dominate the landscape. They state, “If the proportion of cohabitors and non-cohabitors is more or less in equilibrium, selection processes might still be operative, but certainly to a lesser extent than when the proportion of cohabitors is either very high or very low” (p. 206).

Using data from Kiernan (2002), Liefbroer and Dourleijn hypothesize that the variation in observed post-cohabitation marital stability in Europe will be a result of diffusion difference in those countries studied. Specifically stated, they expect the relationship to be curvilinear. Differences should be higher when only a small portion of the population is either choosing to cohabit or choosing not to cohabit. When about half of the population has experienced non-marital cohabitation, they would expect to see the least amount of difference in later marital stability compared to those who go straight to marriage without cohabitation.

Liefbroer and Dourleijn (2006) include a number of variables known to influence cohabitation in an attempt to control for their effect. These covariates included birth cohort, parental divorce, place of residence during childhood, age at the start of the union, educational attainment, activity status, and parenthood. Figure 4.2 shows that union dissolution does explain at least part of the variation in post-cohabitors’ marital stability across Europe. As the populations of countries approach equilibrium of those who have and have not cohabited prior to marriage, the difference in marital stability outcomes decreases. The authors caution that the findings explain only a part of the mechanisms at work and point to other institutional factors, such as religion and legislative regulations, that may be at work. They conclude by emphasizing that the selection effect continues to operate across all scenarios and that the important question continues to be this: What makes the marriages of people who reject unmarried cohabitation so stable?

Variations beyond the European Family Cohabitation as a union formation practice has been extensively researched in the context of the European family. Therborn (2004) states that although Eastern Europe has begun to see a rise in cohabitation, the practice is still rare. Post-Soviet central Russia reported only a few percent practising informal sexual unions, and limited South Asian data showed the Philippines as having adopted cohabitation at a modest level with only 8 percent of women aged 20 to 29 indicating they had done so (Therborn, 2004). In most of Asia and North Africa, and Nigeria (Ladi et al., 2017) cohabitation is not often practiced, and if practiced, is done in a clandestine manner. Therborn (2004) cites 1997 data from Japan showing that among those aged 30 to 34, only 8 percent report sexually cohabiting; among those aged 25 to 29, that number drops to 5 percent. China had less than 1 percent cohabiting in 1989 (Ruan, 1991). However, in China there is a distinction that has been observed between those married in the early-reform period and the late-reform period (Zhang, 2017). For those married in the early-reform period (1980-1994), premarital cohabitation was positively related to subsequent divorce, while the same positive relationship was not observed in those married in the late-reform period (1995-2010), when premarital cohabitation became more common.

Brazil provides a good illustration of how cohabitation has been practised in Latin American culture. Over a period of 50 years, religious marriages dropped from 20 percent of all sexual unions to 4 percent in 2000. On the other hand, consensual unions rose from 7 percent to 28 percent over the same period (Therborn, 2004). The Caribbean picture shows an even stronger adoption rate. Widespread poverty is a known structural factor influencing the adoption of non-marital cohabitation (Ortmayr, 1997). Therborn cites Tremblay and Capon (1988) in stating that two thirds of the sexual unions are unmarried in Haiti and more than 50 percent are unmarried in the Dominican Republic, with Jamaica and Central American countries in the range of 40 to 50 percent.

Adoption rates in African countries vary. These variations can be attributed to the structural influences of religion, socio-economic status, and the unique socio-historical cultures of the represented groups. Cohabitation represents a majority of sexual unions in Mozambique and Gabon among women aged 20 to 24 and one third of unions in Uganda, Ivory Coast, and Ghana among the same age group and sex (Therborn, 2004). The African countries that have significant Muslim and Christian populations have much lower levels of cohabitation.

Diversity of cohabitation patterns is found within the Canadian context as well. Clear differences between the country’s two charter groups is evident, as Quebec’s cohabiting and married couples have similar child-rearing, child-bearing, and union stability patterns (La Bourdais & Lapierre-Adamcyk, 2004). Aboriginal and indigenous groups have much higher adoption of non-marital unions. The immigrant population’s adoption rate resembles the patterns in their countries of origin, whereas the Aboriginal population’s high adoption rate represents a life course that varies from that of the general population in the late adolescent and early adult period (Table 4.2). Aboriginal youth finish their education and leave their parents’ home at a much younger age. As a result, they are more likely to form a union and have a child. Beaujot and Kerr (2007) report that by age 20, 20.6 percent of Aboriginal youth report cohabiting or being married, compared to 8.8 percent of the general population and 6.3 percent of immigrants.

Cross-National Government Policies Regarding Cohabitation Different countries have different approaches to legislation regarding cohabitation. In an additional examination of cross-national cohabitation patterns, Popenoe (2009) found that almost all nations have domestic partnership or registered partnership legislation that provides marriage-equivalent status and protections. Popenoe notes that only France, the Netherlands, and Belgium make this status available to same-sex couples. Divorce laws for these partnerships mirror those for their marriage counterparts. Additional benefits extended to cohabitating couples, such as partner coverage in health insurance and the transfer of a partner’s property upon death, vary considerably depending on the location. What constitutes a couple officially cohabiting also varies considerably and relies on diverse criteria such as ongoing sexual relations, duration of cohabitation, and holding a joint residence. Each country may be marked by heterogeneity when applying these criteria. Australia, Canada, and the United States illustrate this point, as each province or state differs from the next in applying such criteria. Citing research from Waaldijk (2004), Popenoe states that non-marital cohabitation remains distinctive, where it is found, in that no specific procedures exist for getting into it or getting out of it.

Definitions and Legal Issues

The rapid rise in cohabitation around the world has not been accompanied by a systematic legal structure. Bowman (2007, p. 38) writes: “Many people in the United States mistakenly believe that the law in fact does protect them after a certain period of cohabitation, although common law marriage is recognized in only a handful of states.” She goes on to show that even though common-law marriage was abolished in the United Kingdom in 1753, a large-scale survey indicated that a majority of people thought that after a certain period of residence (six months to six years) cohabitants were granted the same rights as married couples. Cohabitation is not synonymous with common-law marriage, although the terms are often used interchangeably. Common-law marriage is typically defined as the union of a couple who consider themselves to be husband and wife but who have not solemnized the relationship with a formal ceremony. Common-law marriage has its roots in medieval Europe, where partners were able to marry formally without any witnesses. Later, religious and constitutional bodies began to demand that marriages be performed by a representative of the church or state and witnessed by additional parties.

Table 4.2 Percentage of Women Married or Cohabiting and Percentage with At Least One Child Aged 5 or Under, Canada

| Percentage Who Are Married or Cohabiting | |||

| Age | All Canadians | Immigrants | Aboriginal Identity |

| 15 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 16 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| 17 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 3.0 |

| 18 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 6.7 |

| 19 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 11.2 |

| 20 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 20.6 |

| 21 | 13.5 | 9.0 | 23.3 |

| 22 | 18.6 | 15.3 | 29.3 |

| 23 | 25.7 | 20.5 | 35.8 |

| 24 | 32.4 | 28.1 | 42.3 |

| 25 | 39.2 | 36.1 | 46.4 |

| 26 | 45.2 | 39.1 | 45.7 |

| 27 | 51.8 | 49.5 | 52.2 |

| 28 | 55.9 | 54.0 | 53.6 |

| 29 | 60.5 | 60.0 | 57.0 |

| Percentage of Women with at Least One Child Aged Five or Under | |||

| Age | All Canadians | Immigrants | Aboriginal Identity |

| 15 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| 16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.0 |

| 17 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 5.6 |

| 18 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 9.5 |

| 19 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 18.5 |

| 20 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 27.1 |

| 21 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 33.9 |

| 22 | 10.5 | 8.3 | 32.6 |

| 23 | 15.6 | 13.2 | 38.1 |

| 24 | 20.2 | 18.9 | 40.6 |

| 25 | 23.1 | 22.2 | 41.5 |

| 26 | 26.3 | 24.1 | 33.6 |

| 27 | 30.2 | 30.4 | 36.5 |

| 28 | 33.3 | 32.5 | 35.6 |

| 29 | 35.4 | 36.6 | 37.5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Public Use Files, Canadian Census, 1991, 2001.

Do Legal Incentives Help?

One important area of interest for social policy-makers is the implication of legislation on the choices couples make with regard to union formation. A brief summary of historical and recent legislative attempts to alter marriage adoption patterns reveals the resiliency of marriage as an institution. A well-documented attempt to alter marriage laws is found in the Bolshevik family law reforms. Bowman (2007) interprets Wardle’s (2004) work to show that despite attempts to reduce the distinction between marriage and cohabitation, there is no evidence to support the idea that the institution of marriage was harmed. In 1980, the marriage rates in the former Soviet bloc nations of Belarus (10.1 percent), Russia (10.6 percent), and Ukraine (9.3 percent) exceeded those in the United Kingdom (7.4 percent) and Italy (5.7 percent) and were on par with those in the United States (10.5 percent). Only after the fall of the Soviet Union did marriage rates in these former Soviet bloc countries begin to fall to the levels in other Western nations. In 2001, the marriage rates in Belarus (6.9 percent), Russia (6.9 percent), and Ukraine (5.6 percent) were much lower than they had been under Bolshevik family law. The development and evolution of family policy and its effects are more complex (see Waters [1995] for a more detailed analysis of Bolshevik family law) than simple attempts to destroy the family for state purposes, yet they do present a compelling glimpse at a modern attempt to legislate family change through marriage and divorce law.

The impact of legislation on union formation can also be seen by looking at current protections offered to cohabitants in various countries. Bowman (2007), for example, shows that even though extensive legal protections are offered to cohabitants in the Netherlands, Sweden, and France, the rate of cohabitation is not necessarily different from that in countries without the same protection. In the Netherlands, the legal protection offered to cohabitors means that no distinction exists between them and those who marry, yet the cohabitation-to-marriage ratio of 25 percent is the same as in the United Kingdom, where legal protection is denied to cohabitants. Citing data from Sweden, France, and the United States, Bowman (2007) concludes that offering legal recognition and support for cohabitation does not discourage marriage but may in fact encourage it. In Sweden, where cohabitation has a long history of favourable treatment, 61.2 percent of cohabitants eventually marry their partner, compared to 48 percent in the United States. Other researchers do not see the same neutrality of the legislation. Popenoe (2009) argues that although the Nordic nations have high levels of cohabitation, they also attach the most legal consequences to it; Germany, which has a low level of cohabitation, attaches the least legal consequences to it. Popenoe feels that legislation is written after the widespread acceptance of cohabitation and therefore puts a stamp of approval on the practice. Popenoe concludes by arguing that this trend weakens the distinctive cultural and legal status of marriage.

Property and Child Custody

The lack of standardized legal treatment of cohabitation leaves the distribution of assets and assignment of child custody to local magistrates, should the union cease. Because cohabitation is often not a structured event, the ending of the union faces the same lack of clarity. This affects the legal rights one may have to property and possessions acquired during the union and the custodial rights of parents, especially if children are brought into the union. Legal professionals advise clients who cohabit to establish legal agreements regarding significant assets such as a home. Without specific laws in place to ensure the equitable distribution of assets, one party may be at a disadvantage when the union dissolves. This disadvantage is usually the woman’s in a heterosexual partnership.

Asset Protection Approaches to the legal rights regarding both property rights of individuals and child custody rights are divided into two categories: proactive and reactive. Proactive approaches include those strategies that an individual may take advantage of prior to dissolving the union. Reactive strategies are those strategies available to individuals after they have ended the union.

With regard to asset protection and estate planning, a cohabiting couple must realize their rights as a couple apart from marriage law. This may include special state or provincial protections for registered partnerships or for couples who meet the types of criteria associated with a recognized cohabiting union. In the United States, the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was passed by Congress in 1996 to establish the definition of marriage as the legal union of a man and a woman. Primarily introduced to prevent states from having to recognize same-sex couples married in other states, the law also established who was entitled to federal spousal and tax benefits.

Because each legal jurisdiction may have its own laws concerning cohabitation, it is difficult to summarize them. A few key concepts are cohabitation agreements, civil unions, and domestic partnerships. These are not identical concepts and they do not provide the same rights as marriage. Many jurisdictions do not recognize cohabitation agreements, since they attempt to circumvent laws (such as DOMA) designed to protect the distinctiveness of marriage. Domestic partnerships have more legal recognition but that recognition is not universal across the United States. In the states, cities, and counties in which they are recognized, domestic partnerships tend to follow a standard definition containing the following elements: (1) partners are at least 18 years old, (2) neither partner is related by blood closer than what is permitted by state law for marriage, (3) the partners share a committed exclusive relationship; and (4) the partners are financially interdependent. Currently, only the District of Columbia, California, Hawaii, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin offer some form of domestic partnership (Hickey, 2009).

The legal tools available to non-married couples are diverse and generally mirror

the tools for non-residential partnerships. Hickey (2009) recommends cohabitation agreements if the long list of criteria needed to make them binding are met. She also suggests that other estate planning tools be put in place as well as items such as power of attorney, living wills, and health permission release forms (so medical professionals can talk about a patient to non-kin). In addition to what is needed during the lives of the partners, there is the matter of dealing with the transfer of assets upon the death of one of the partners. Without formal arrangements, the assets will not automatically go to the surviving partner. Designating one’s partner in a will makes it easier to transfer assets, but it is also possible to look at specific financial accounts and designate a beneficiary who is different from that in the will and will actually supersede what is in the will. Financial assets such as life insurance, retirement accounts, bank accounts, annuities, and trust accounts can all be designated to one’s partner rather than to a legally recognized family member.

Child Custody Child custody issues are another concern for couples who do not have legislative protection. Custodial concerns for cohabiting couples do not focus on children born within the union, for which both parents would be legally granted parental rights, but on a non-biological partner’s rights to parental authority and visitation. This is relevant not only in the context of an intact relationship (e.g., the issue of medical decisions) but also to clarify the rights and responsibilities of each partner if the union dissolves. Kunin and Davis (2009) define the importance of the latter scenario using five facts: (1) the couple has resided together for a significant period of time, (2) a parental relationship has been established between the child and the individual with no parental rights, (3) the parties have ended the relationship, (4) there is no traditional second legal parent, and (5) the parent without parental rights has been alienated from the child. The authors explain that these criteria would apply to both heterosexual and homosexual unions in locations where both types of union are recognized.

Proactive strategies include second-parent adoption, co-guardianship, and a

cohabitation agreement. Second-parent adoption suffers from limited availability. In the United States, most states have laws that allow single adults or married couples to adopt; the idea of second-parent adoption is limited to only a few states. Co-guardianship is another option when second-parent adoption is not available. It ensures that all responsibilities of a legal parent, such as making medical decisions for a child, would remain in place upon dissolution of the union unless a partner petitions to have these responsibilities removed and provides reasons why this would be in the best interests of the child. Cohabitation agreements suffer from the limitations

discussed in section above on asset protection. They are recognized in only a few locations and, in the case of the United States, may be void because of being superseded by DOMA.

Table 4.3 Similarities and Differences between Married and Unmarried Couples in Canada

| Married | Common Law | |

| Equalization payment upon separation | Yes | No, but may be claim for unjust enrichment |

| Possession of the matrimonial home upon separation | Yes | No |

| Special treatment of matrimonial home in dividing property | Yes | No |

| Spousal support | Yes | Yes, if lived together for 3 years or are in a relationship of some permanence and have children |

| Time limit to apply for spousal support | No | Yes in several provinces |

| Older restraining depletion of property | Yes | No, but can use Rules of Civil Procedure for similar sorts of orders |

| Child support | Yes | Yes |

| Child custody | Yes | Yes |

| Succession rights if partner dies intestate | Yes | No, but may be claim for unjust enrichment |

| Dependant’s relief on death of partner | Yes | Yes |

| Equalization payment on death | Yes | No, but may be claim for unjust enrichment |

| Possession of matrimonial home on death | Yes | No, but maybe able to claim as an incident of support |

Source: www.common-law-separation-canada.com

The only proposed reactive strategy to child custody issues for cohabitants is to petition for third-party visitation rights. This strategy is a long shot since, in a best-case scenario, it only begins to approach the rights of a non-custodial parent and requires proof that the legal parent is unfit in some capacity. Child custody options for non-biological partners in cohabitation reveal the uncertainty surrounding future parental rights.

Internationally, conditions similar to those in the United States exist. Countries with greater legal protections for cohabitation will have laws that more closely resemble those governing marriage. In most cases, there are regional differences within a country. Table 4.3 provides a general outline of the similarities and differences between married and unmarried couples in Canada, Box 4.3 highlights how these two relationships differ when they end, and Box 4.4 discusses how these relationships are taxed.

| Box 4.4 |

| The Main Differences upon Separation between Being Married and Being in a Common-Law Relationship |

| Common-Law Relationship

In William Shakespeare’s play All’s Well That Ends Well, a French orphan named Helena attempts to win the love of Count Bertram. Unfortunately, despite Helena’s beauty, the social class differences between the couple make the match seem impossible. Through a series of events involving the timely administration of the healing arts that Helena learned from her physician father, she is able to save the king; as a reward, she is given the hand of any man in the realm, and of course she chooses Bertram. The wedding takes place and then the relationship goes poorly very soon thereafter. Bertram is appalled by the match, flees the country, and refuses to honour his wedding vows unless Helena can get his family ring from his finger and become pregnant with his child. Helena’s wisdom exceeds her beauty and she is able to use Bertram’s attempts to seduce a young virgin to trick him into giving her the ring and getting her pregnant. All’s Well That Ends Well is the story of a relationship with twists and turns including fighting over family possessions, relationship legitimacy, and relationship stress and breakdown. As in Shakespeare’s play, relationships don’t always work out as planned. How they end and what happens to a couple’s possessions after a relationship breaks down depends a great deal on how the relationship is defined. There is often confusion and misunderstanding regarding the legal rights and responsibilities that common-law partners have to one another when a relationship breaks down. This confusion frequently results from differing definitions and legislation regarding couples living together. The key areas to consider include the following. Division of Property The equalization of net family property occurs when a person’s net worth (assets minus debts) at the date of relationship separation is compared to his or her net worth (assets minus debts) at the date of marriage. The net change in each person’s worth at the date of separation is the net family property. The partner with the larger growth in net worth is ordered to pay half of the difference between the two net worth amounts as an equalization payment. In common-law relationships, a problem occurs in that this equalization of net family property is required only by those who meet the definition of being legally married. This law has been challenged, but the Supreme Court of Canada has stated that the difference is not discriminatory, insisting that people’s choice to marry or not is a personal one and that marriage and cohabitation are not the same. The Matrimonial Home When a marriage ends, generally there is an automatic right to stay in the matrimonial home, even if it is not in one’s name. In Ontario, however, this is not the case. If you are not married and your name is not on the home, you have no legal claim to it. A distinction also exists in how the matrimonial home’s value is divided upon its sale. Unlike the division of other assets, which are subject to the formula discussed above, the value of a matrimonial home is automatically divided between the spouses. However, this is not the case for couples in a common-law relationship. Spousal Support Married couples have automatic responsibilities to receive or pay spousal support. There is also no time limitation to make a claim for spousal support. This is not the case for common-law relationships in parts of Canada. In Ontario, for example, a couple must meet the stricter criteria of having lived together for three years or having had a child together. As well, a claim for support must be made within two years of separation. Protection Against the Depletion of Property If you are concerned that your partner may go on a spending spree to deplete his or her assets before having to divide them, then being married will protect you but being in a common-law relationship will not. Common-law partners cannot obtain a court order to prevent the partners from depleting assets, but married partners can. Inheritance If you are married, you are automatically entitled to receive a share of your partner’s estate, even if he or she dies without a will. If the will seems to provide an unfair settlement, married partners can seek an equalization payment to compensate for this. Those in a common-law relationship do not enjoy these same rights; instead, the surviving partner must bring a claim for unjust enrichment against the deceased partner’s estate. |

| Box 4.5 |

| Canada Revenue Agency’s Definitions of Marital Status |

| In the Information about you area, tick the box that applied to your marital status on December 31, 2009. Tick “Married” if you had a spouse or “Living common-law” if you had a common-law partner. You still have a spouse or common-law partner if you were living apart for reasons other than a breakdown in your relationship.

Tick one of the other boxes only if married or living common law does not apply to you. Note If you are entitled to any GST/ HST credit, Universal Child Care Benefit, or Canada Child Tax Benefit payments, or Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB) advance payments, and your marital status changes during the year, be sure to let us know and send us a completed Form RC65, Marital Status Change. Spouse This applies to a person to whom you are legally married. Common-law partner This applies to a person who is not your spouse (see above), with whom you are living in a conjugal relationship, and to whom at least one of the following situations applies. He or she: a) has been living with you in a conjugal relationship for at least 12 continuous months; b) is the parent of your child by birth or adoption; or c) has custody and control of your child (or had custody and control immediately before the child turned 19 years of age) and your child is wholly dependent on that person for support. Before 2001, an individual would also immediately become your common-law partner if you previously lived together in a conjugal relationship for at least 12 continuous months and you had resumed living together in such a relationship. Under proposed changes, this condition no longer exists. Currently, a person (other than a person described in b) or c) will be your common-law partner only after your current relationship with that person has lasted at least 12 continuous months. This proposed change will apply to 2001 and later years. Note The term “12 continuous months” in this definition includes any period that you were separated for less than 90 days because of a breakdown in the relationship. Source: Canada Revenue Agency, www.cra.gc.ca. |

Factors Influencing Cohabitation

Intergenerational Cohabitation

Early research on the subject of cohabitation identified the importance of parental influence on the union formation patterns of their offspring. Axinn and Thornton (1992) found that children’s non-marital cohabitation patterns were correlated to mothers’ attitudes toward cohabitation. Their more recent work (Thornton et al., 2007) outlines numerous intergenerational influences on union formation patterns extending back as much as two generations (see Table 4.4). Manning, Cohen, and Smock (2011) examine the influence of parents and peers on emerging adults’ decisions to cohabit. They put forth the idea that emerging adulthood may be more sensitive to social context than adolescence because of the developing and changing dynamic with romantic partners, family, and peers during this period of development.

| Table 4.4 Intergenerational Factors Affecting Cohabitation |

1. Parental Factors during Childhood and Adolescence

2. Parental and Child Factors during the Children’s Young Adulthood

|

Source: Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Xie, Y. (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Reprinted with permission.

Data on the intergenerational influences of parents on their children’s relationship pathways demonstrate that they do influence their children’s decisions, whether in the form of an arranged marriage or some other form of socialization. Marriage formation and stability have been linked to a number of parental attributes such as religiosity, education, socio-economic status as well as to the family structure and the parents’ marriage stability. Children of divorced parents are less likely to marry and, when they do, their marriages do not last as long as those raised in two-parent, intact homes (Cherlin, 2009). Although much work has been done on the influence of parents in guiding and influencing their children’s marriage selection, timing, and stability, the intergenerational effects of cohabitation are just now reaching the forefront of social research. Twenty-first-century young adults (particularly those in North America) are the first generation to grow up in a society in which cohabitation was socially acceptable for their parents and a modal state for their peers – Manning and colleagues (2019) found that as much as 54% of single Millennial women expect to cohabit before marriage. As would be expected from learning theory and parental socialization, early research shows that adolescents who grew up in a cohabiting-parent family are more likely to expect to cohabit than adolescents who were not part of a cohabiting parental environment (Manning, Longmore, & Giordano, 2007). In addition, young adults whose parents cohabited were more likely to have cohabited than their counterparts (Lonardo, Giordano, Longmore, & Manning, 2009; Sassler, Cunningham, & Lichter, 2009).

Religion is another mechanism through which the intergenerational influence on cohabitation is transmitted. Religion and religious traditions encourage family values that emphasize the importance of one’s relationship to parents and the centrality of marriage (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). Together, religion and family form a strong influence in establishing and maintaining the importance of the family and, by extension, marriage. Cohabitation patterns have been shown to correlate to one’s religious orientation (Lehrer, 2000). Religious individuals are less tolerant of sexual expression outside of marriage and therefore do not look favourably on cohabitation as a legitimate form of committed relationship, although general acceptance and practice has been increasing among religious adherents concurrently with the general population. As mentioned earlier, the influence of parents and peers on one’s religious beliefs and practices is clearly documented. As parents socialize their children in religious traditions and beliefs, they are also influencing the likelihood of marriage instead of cohabitation. Manning et al. (2011) suggest that religious beliefs affect a couple’s decision to cohabit when one or both partners do not want to go against what they have been taught to believe from their parents regarding the acceptability of cohabitation. Not wanting to disappoint extended family may also play a part in the couple’s choice.

Marie Cornwall’s (1989) channelling hypothesis would apply in the area of cohabitation acceptance. Parents who desire to steer their children toward certain beliefs and behaviours often will channel their children into supporting socialization opportunities such as parochial schools and carefully control the child’s peer network. This process can be seen to influence the intergenerational transfer of cohabitation beliefs and practices. Manning et al. (2011) recognize the role and importance of adolescent peer socialization in forming attitudes and behaviours regarding the opposite sex. They cite a variety of authors (Brown, 1999; Cavanagh, 2007; Collins, Hennighausen, Schmit, & Sroufe, 1997; Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000; Hartup, French, Laursen, Johnston, & Ogawa, 1993) who support the influence of adolescent peers but state that limited research is available for emerging adults and conclude the following: “Past theoretical and substantive findings have suggested that peers should have some influence on the nature and course of romantic relationships in early adulthood” (Manning et al., 2011, p. 122). They also provide support for peer influence through modelling. Using research from Japan (Rindfuss, Choe, Bumpass, & Tsuya, 2004) and Germany (Nazio & Blossfeld, 2003), they show that emerging adults look to the patterns and experiences of their peers as a guide to their own cohabitation behaviour. In addition, Arnett (2004) states that emerging adults look to peers’ marriage experiences as a guide to their own opportunities. It would then be expected that they also look to their peers for direction in cohabitation choices.

Image 4.2

Traditionally, marriage has played an important social role in the transition to adulthood (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some societies, it was the only legitimate transition out of single status. Marriage also legitimized childbirth and, as a result, established kinship connections that had enduring impact in the form of inheritance and social identity. As cohabitation becomes more normative, some of the distinctions between marriage and cohabitation are being removed. Marriage no longer serves as the sole means to legitimize a committed relationship and non-marital fertility is rising among both cohabitors and non-cohabitors. The lack of social clarity surrounding cohabitation has led to divergent relationship pathways of those embracing it. Motivations for cohabitation are often diverse, serving different purposes for different groups (Guzzo, 2008). This fact is true with racial and ethnic differences (Manning, 1993; Manning & Smock, 2002), gender and life course stage (Oppenheimer, 2003), age (Moustgaard & Martikainen, 2009), economic status (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2004), and historical periods (Schoen, 1992).

Transition to Adulthood

Age-graded institutions such as education, workplaces, and marriage laws give structure and regularity to the life course (Hogan & Astone, 1986). These regularities change over historical periods and cohorts and, as a result, change the way in which transitions from adolescence to adulthood vary. For example, more males and females are continuing their education for longer periods than in previous generations since workplaces require greater and greater training. As a result, young adults are delaying marriage and choosing to cohabit instead (Thornton et al., 2007; Manning et al., 2019). Passage to adulthood has typically been associated with five major events: leaving home, finishing one’s education, getting a job, marrying, and having children. Because of extended education, all of these events have been delayed compared to previous cohorts (Beaujot & Kerr, 2007). Not only has the transition to adulthood been delayed, but it seems less permanent and is non-linear and subject to reversals (Mitchell, 2006).

In a recent analysis of Canadian census data, Clark (2007) showed that over a period of 30 years (1971 to 2001) the number of transitions made by age of young adults continued to decline. In 2001, the typical 25-year-old had gone through the same number of transitions as a 22-year-old in 1971. In comparison, a 25-year-old in 1971 parallels a 30-year-old today. Studies over longer periods indicate that during the two world wars the time of transition in these five areas was compressed, but after World War II until the present that the transitions have gradually extended into later ages.

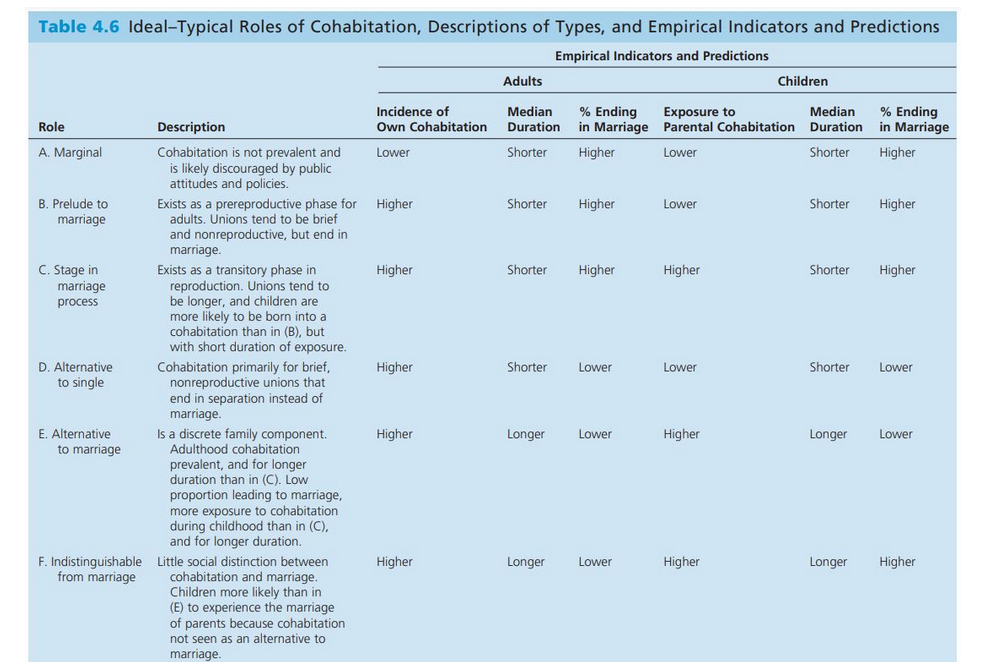

Courtship Patterns and Pathways

Ever since early moral philosophers and social scientists such as Bertrand Russell and Margaret Mead advocated cohabitation as a precursor to marriage, a diversity of pathways into and out of a cohabiting relationship have been travelled. This section briefly discusses the deliberateness of entering a cohabiting relationship in contrast to drifting into one in a social context that does not sanction it. After this overview, three different typologies of cohabitors will be presented in Table 4.5 to provide you with a glimpse of the heterogeneity that exists in the conceptualization and study of cohabitation. How couples approach cohabitation and how they see its role in future relationship status changes are quite important in predicting the length of cohabitation and whether children will be brought into the union (see Table 4.6).

| Table 4.5 Typologies of Cohabitation in Relation to Marriage and Being Single |

| Thornton, Axinn, and Xie (2007)

1. Being single and cohabiting as equivalent contrasts to marriage 2. Marriage and cohabitation as equivalent contrasts to marriage 3. Marriage and cohabitation as independent alternatives to being single 4. Marriage and cohabitation as a choice conditional on the decision to form a union 5. Cohabitation as part of the marriage process Casper and Bianchi (2002) 1. Substitute for marriage 2. Precursor to marriage 3. Trial marriage 4. Co-residential dating Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) 1. Marginal 2. Prelude to marriage 3. Stage in marriage process 4. Alternative to being single 5. Alternative to marriage 6. Indistinguishable from marriage |

More attention is being paid to the deliberateness of a couple’s entry into cohabitating relationships as a possible clue to a negative correlation to marital outcomes. This is especially important for those who see cohabitation as a screening process that weeds out potentially unsuccessful relationships before marriage. Stanley, Rhoades, and Markman (2006) describe the gradual steps that culminate in a non-residential intimate relationship as sliding (see Box 4.5). They note that Manning and Smock (2005) found that many, if not most, couples slide from non-cohabitation to cohabitation before fully realizing what is happening. This supports earlier work by Lindsay (2000) that concluded from a study of Australian focus groups that most couples say that cohabitation “just happened,” indicating a lack of formal decision making about the transition to cohabitation. This “decisionless” union formation is associated with lengthier periods of cohabitation regardless of whether the cohabitation becomes a pathway to marriage or is dissolved. This relates to the fact that length of cohabitation has been shown to have important implications for later marriage outcomes. Earlier research showed that relationship risk for couples who cohabited for short periods (less than six months) prior to marriage did not differ from those who took a direct pathway to marriage (Teachman & Polonko, 1990). The authors concluded that this is probably the result of engaged couples moving in together prior to their imminent wedding. Yet De Vaus, Qu, and Weston (2005) found that, after controlling for selection effects, those who cohabitated for longer than three years prior to marriage had a separation rate significantly lower than those who went directly to marriage.

[Table 4.6] Ideal-Typical Roles of Cohabitation, Descriptions of Types, and Empirical Indicators and Predictions

Source: Heuveline and Timberlake (2004, p. 1219).

| Box 4.6 |

| Sliding or Deciding? |

| After a few months of dating, Lee and Sasha decided that with school ending, moving in together for the summer seemed like the financially smart thing to do. Before they knew it, they had a shared cellphone plan, had co-signed for a used car loan, and had spent more than a few dollars at IKEA outfitting their new place. Summer came and went—three times!

Lee and Sasha were comfortable together and enjoyed each other’s company, but where was this relationship going? One day, Sasha broached the topic and Lee got prickly. He did not want to talk about it. Even though they had seemed compatible and enjoyed each other intimately, the thought of greater commitment made Lee uneasy. Sasha decided to try another strategy. She told Lee that a recent study (Barg & Beblo, 2007) showed that men who married made over 13 percent more than those who stayed single. Lee responded by saying that he had read the study as well and that those who lived with a partner saw an almost 7 percent increase in wages over those who remained single, and he didn’t think the other 6 percent was really worth it. As Sasha reflected on the ambiguity of it all, Lee grabbed the TV remote and hit play. |

Transition rates across the life course have been found to be important in the attempts to disentangle the cohabitation effect. The importance of frequent transitions across the life course is often missed because of focusing on only one aspect of the life course such as labour force attainment, family formation, housing, or parenthood. Life course trajectories are seldom linear and often involve “U-turns, detours and yo-yo movements in and out of statuses” (Martin, Schoon, & Ross, 2008, p. 180). Specific to cohabitation periods, Lichter and Qian (2008) found that female serial cohabitors (defined as cohabiting two or more times) who eventually married increased their odds of divorce by 141 percent, or almost one and a half times, compared to those who cohabited only with their future husband, even after controlling for past fertility and socio-economic characteristics. Complex life courses differ in outcome from those life courses that are more stable (Stanley, Rhoades, Amato, Markman, & Johnson, 2010; Teachman, 2008).

Stanley et al. (2006) summarize the reasons why, after several decades of research, they believe the academic community is still unable to answer the “why” question regarding the negative influence of premarital cohabitation on later marital quality and stability.

“Although there have been notable advances in knowledge, we know far less than we would like about why, and under what circumstances, the cohabitation effect occurs. This is in part because of limitations in the existing literature, the three greatest being (a) a lack of theory, (b) a general dearth of longitudinal methods with sufficient sensitivity and quality of measurement, and (c) the fact that a vast number of studies published on the cohabitation effect are from a single, now aging data set (the National Survey of Families and Households). (pp. 499–500)”

Effects of Cohabitation

Cohabitation and Later Effect on Children

Parental cohabitation and its impact on children across the life course has been gaining interest as a research focus. The complexity of the issues influencing child outcomes is being understood more fully. Early research predicted that cohabitation would have negative outcomes on child development. Several explanations were put forth by Bulanda and Manning (2008). The instability of cohabitation in comparison to marriage was identified as one potential problem since parental instability has been shown to lead to negative child outcomes. Lower educational level of cohabiting couples was another potential problem put forth. A third was that a selection effect was at work. By selection effect, the authors are referring to the idea that mothers with children who have behaviour problems may be less attractive marital partners and therefore choose cohabitation instead of remaining single. Parents with weaker parenting abilities may be more highly represented among those who cohabit. This last explanation ties in to the lack of legal and social benefits to which married parents have access. Without clear social or legal definitions of responsibility, non-biological parents in particular may be a poor influence on a child’s behaviour.

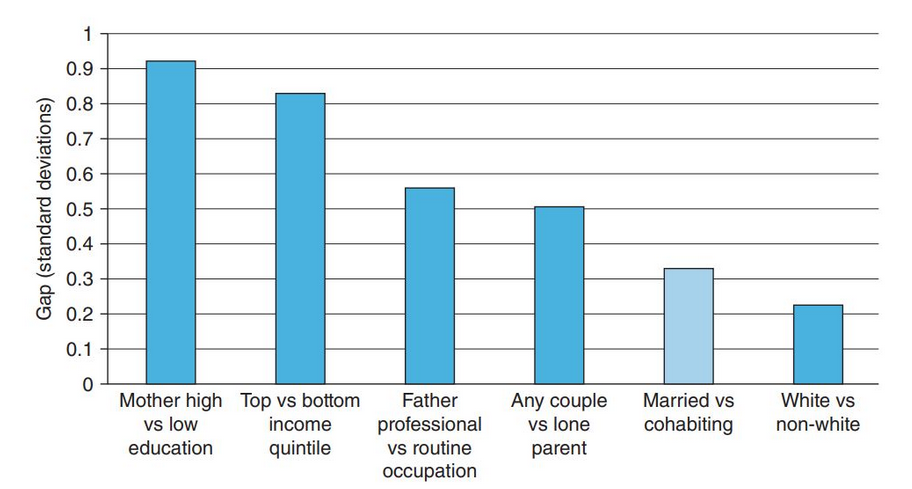

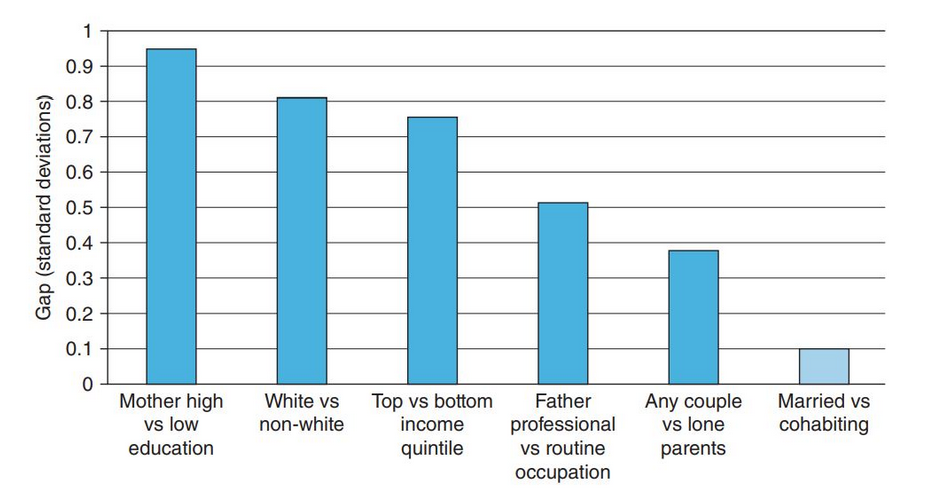

A recent project in Britain based on the Millennium Cohort Study showed less positive outcomes among young children in a cohabiting home than those in a home in which the parents were married (see Figure 4.3). The study looked at almost 19 000 new births across the United Kingdom around the turn of the millennium. The children were visited at ages 9 months, 3 years, and 5 years for assessment of developmental measures. The study found that, on average, children born to cohabiting parents scored lower than those born to married parents on social and emotional development (as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ]) and cognitive development (captured by the British Ability Scales [BAS] vocabulary element). It is important to note that although children born to cohabiting parents scored lower than those born to married parents, the differences were not as large as socio-economic factors such as parental education, family income, and occupational measures (see Figures 4.4 and 4.5). A study conducted in Quebec, however, found that there were no negative associations between academic performance and children living in a cohabiting home compared to children living in a home in which parents were married (Lardoux & Pelletier, 2012). In fact, there was a small positive relationship between the cohabitational relationship of parents and the academic performance of girls.

Figure 4.2 Differences in Social and Emotional Development (SDQ) and Cognitive Development (BAS) between Children Born to Married and Cohabitating Couples, at Ages 3 and 5

Source: Data from the Millennium Cohort Study.

Figure 4.3 Differences in Social and Emotional Development between Children of Married and Cohabitating Couples in Context (Age 3)

Source: Data from the Millennium Cohort Study.

Figure 4.4 Differences in Cognitive Development between Children of Married and Cohabitating Couples in Context (Age 3)

Source: Data from the Millennium Cohort Study.

Research has focused not only on outcomes of young children but also on outcomes of adolescents. By looking at adolescent outcomes, the research is able to take more of the family life history into consideration. Bulanda and Manning (2008) found that living with cohabiting parents is correlated to earlier sexual initiation, a greater likelihood of teen pregnancy, and lower rates of high school graduation compared to those adolescents who grew up in a married-parent household. However, their study found that the simple explanation of parental union instability was insufficient to explain why the negative adolescent outcomes existed. One explanation presented involved the idea of more parental monitoring being associated with later sexual initiation and later teenage pregnancy. The authors contemplated the idea that cohabiting parents may invest less in their parental relationships, leading to the adolescent outcomes that do not differ from those associated with single-parent families.

Cohabitation and Later Marital Quality

Research on premarital cohabitation has consistently shown a negative impact on later marital stability and quality (DeMaris & Rao, 1992; Hall & Zhao, 1995; Lichter, Qian, & Mellott, 2006; Liefbroer & Dourleijn, 2006; Lillard, Brien, & Waite, 1995; Sassler, 2004; Teachman & Polonko, 1990), while one study showed that married couples who have cohabited have a lower rate of dissolution in the first year of marriage, and a higher rate after five years of marriage (Rosenfeld & Roesler, 2019). Researchers are divided on the explanation for this persistent correlation. Early research in the area suggested that selectivity (Lillard et al., 1995; Phillips & Sweeney, 2005; Smock, 2000) may be the cause of this negative impact. Other researchers (Axinn & Barber, 1997; Axinn & Thornton, 1992; Brown, Sanchez, Nock, & Wright, 2006; DeMaris & Rao, 1992; Hall & Zhao, 1995) suggested that the actual experience of cohabitation was the precursor to the poorer outcomes. Another group of researchers see this effect as an inaccurate conclusion based on analysis of earlier cohorts of cohabitors who cohabited when this was not considered a normative pathway to marriage. These researchers point to more recent cohort studies that do not reflect the earlier findings (Brown, Lee, & Bulanda, 2006; De Vaus et al., 2005; Hewitt & De Vaus, 2009; Hewitt, Western, & Baxter, 2006; Schoen, 1992; Seltzer, 2004). However, other current literature does seem to support the earlier conclusions regarding the negative impact of premarital cohabitation on later marriage outcomes (Kamp Dush, Cohan, & Amato, 2003; Kline et al., 2004; Phillips & Sweeney, 2005).