VISA 582/583 is a studio course for graduate students in Visual Arts. The course focusses on the production of independent artwork and the critical analysis of that work.

Natasha Harvey

Huiyu Chen

I used to believe that my passion for art lay in examining the relations between individuals and the world, which is still so true in a way, but now I have begun to realize what my heartwood—the art’s original germinating seed (Warland 24)—truly is: me, the exploration of myself.

Who are you? This question seems so simple, but I have no answer for it. I am definitely not just a name or a bundle of other labels like “Chinese” or “artist”. How could those labels define me and my art? For me and my art, labels are not identifications but limitations. Who are you? I’m just like Alice answering this question “I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then” (Carroll 48). I cannot explain myself to begin with.

Things inside my bodyshell change every minute. I am a container. The relations between myself and the whole world make me myself. If there was only me, I would be empty.

“Poetry is a form of extrasexual procreation” (Fulton 104). This is how American poet Alice Fulton describes her creative process behind her poems. My art for me is the extrasexual procreation of me and the world. Self-exploration is my art-making methodology, and art is my attempt to explain myself, to figure out the relations I have with this world.

“My body’s struggle to express… [is] nothing other than the world’s struggle to express itself through me, as if I were an organ of this single massive body named Nature” (Toadvine 279). The relations and connections between me and nature are too complicated to quantify. I’m trying to express myself by reflecting the irreducible communicative affects that I undergo in the world—my feelings and emotions. However, I don’t know if it is me reflecting myself in nature or if it is nature reflecting itself in me, or even expressing itself directly through me.

Influenced by artist Jeff Wall as I am, I use various media to create scenes—the artificial reality that I created in my grandma’s waste dining room and the scene I set with masks and my old couch. What Jeff Wall said about his photography— “what you see happening happened, that’s all I have to tell you, how it happened is secondary to the fact it happened” (Wall)—influenced me not only on my creative process, but also on how I look at the things that I cannot explain within myself. Different materials have different textures, and different things trigger different emotions. I do not need to narrate the non-narrative things within me and my art, the audience would re-narrate the things of their own by looking at it.

The exploration of materials will continue. The exploration of myself will not end. The creating of art will never stop. I may never give a complete answer for the question “Who are you?” I am just taking things out of my bodyshell to narrate the non-narrative relations between me and the world.

Kayti Barkved

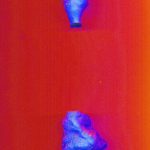

Scott Moore

Tumbling Mustard

Sam Neal

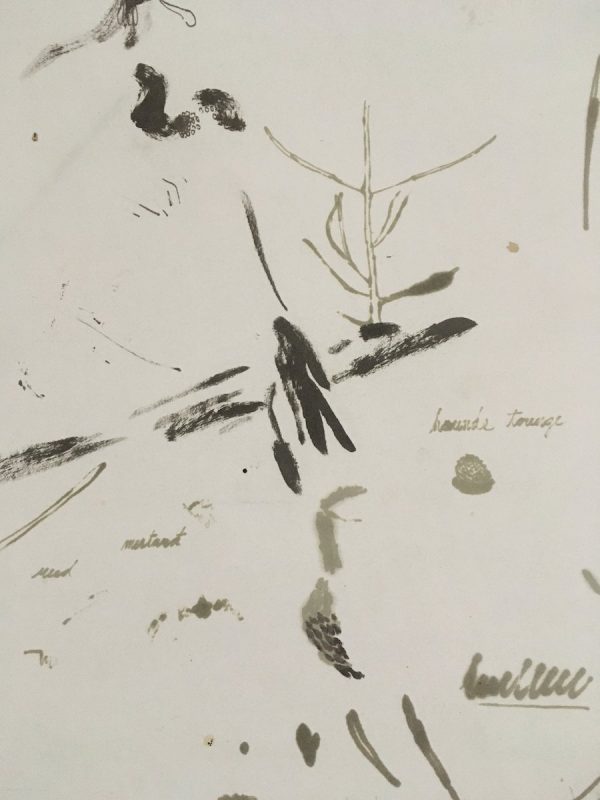

I explore how alternative processes in photography do not have to conform to rules and how the aesthetic of these alternative processes is influenced by nature. The cyanotype is the alternative process that I use. I explore how the body performs with the land to create a tangible piece of art. The resulting piece of art questions how water interacts with objects and humans, how the human performs with nature and how we can document a place through an abstract map.

I have been drawn to how water can appear to change color when light moves across it, how we can see water’s surface and its depths and how it reflects and refracts to create caustics. The process of the cyanotype breathes simplicity, yet the changing ways in which we can manipulate the material and challenge how the cyanotype will be displayed on a wall of a gallery space are diverse. Since the cyanotype was first realized by John Herschel in 1842 and then utilized by Anna Atkins by creating a series of botanical records of algae to make the first photography book, the cyanotype and alternative processes of photography have been challenged in many ways. Contemporary artists such as Susan Derges and Laurie Kang challenge how we can use camera- less photography and how we can manipulate objects and build relationships with the land.

The collaborative nature of the cyanotype process involving myself and the body of water embraces the unknown possibility of what the outcome of the work will be. The process that relies on the collaboration with nature cannot be fully controlled. It is my decision where and when to place the sensitized paper into the water and how long I leave it to expose. How many times the waves wash over the paper is my decision. All of these become part of a scientific and calculative response to the making of the work. Although I open up my body to the surroundings and let nature affect the work in whichever way it wants to, I put these measures in place to enable me to control the initial making of the work and give the best possible chance for a visually striking work. The encounter with the water, however, has its impact on the outcome that I cannot control. Cold weather makes the cyanotype fragile and brittle, freezing the surface of the water that sits on the paper. When the paper dries it leaves fascinating textures leftover by the water that would not have occurred if the performance of the transformation was interrupted. Nature decides the force of the impact with the paper and how it affects it. This can be seen in some of the pieces I have created. Some reflect a sense of calmness and some reflect chaos. Different weather affects the process and the very nature of the environment is the ultimate decision-maker in how the process carries itself into the studio space where it will live.

Brittany Reitzel

Jacen Dennis

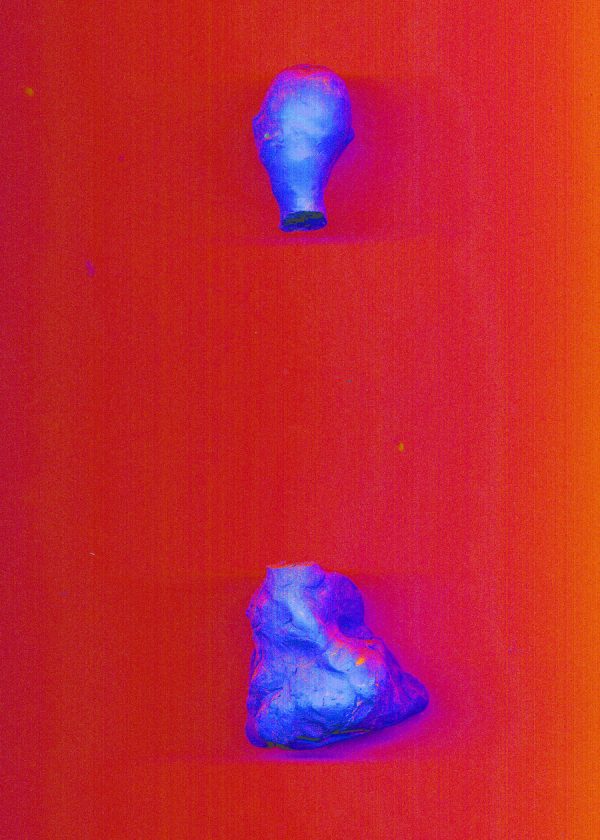

seen and unseen

I position myself as a transgender artist, who started transitioning shortly before my sister died. My artwork links relationship between my gender transition and my sister’s recent death, of connecting a new body to the past, and a past body to the future. I use the method of active imagination to access a link between the conscious and unconscious, and expressive art therapy to transfer those insights into a digitally animated artwork. Utilizing dawning, writing, and verbal journaling I record gender transition and the trauma of a sudden loss as experienced in the body and mind.

The two artworks shown in this MFA Open House, it both nourishes and consumes and her grass that grew thereafter belong together, a reflection of each other by way of what will be an opposite-facing diptych. This particular portion of my final MFA Thesis artwork will be referred to as the seen and unseen diptych.

Both of these works express the idea of physical realities seen and unseen. The experience of the graveside, and of the invasive imagery that pervades my thoughts expresses a morbid need and consequent fear to be aware of what is unseen. Through my journaling and active imagination sessions, this invasive imagery based in the gravesite unseen, under the surface, is driven primarily by a need for continued affirmation in what has happened, in the loss that has occurred. There is also an aspect that is only expressed by a phrase that continues to come to the surface; ‘I just want to know she’s okay.’ What is seen, what is above the ground, is not good enough. The graveside seen, the grass, itself grows and moves and is alive in every way I cannot expect the unseen graveside to be. The animation the grass therefore takes, is dream-like, lethargic, and lacking reality.

The artwork it both nourishes and consumes has an opposite relationship with physical reality both seen and unseen. The ‘it’ in the title references the experience of hormone replacement therapy, of beginning a medical portion of my gender transition. The new hair that grows on my body is affirming and unlike the grass, enforces an experience that is accepted and embraced. As for the unseen, in the development of it both nourishes and consumes during active imagination sessions, the imagery of blood and atrophy occurred regularly. Mirrored opposite to the joy of the visible transformations, the knowledge of the internal is unwanted. Invasive imagery like that of the unseen graveside, but without the impulse to know more of what is taking place. Unlike the unseen graveside, the unseen internal body brings no confirmation of knowledge I need. The knowledge I require is simply evident on my body’s surface.

The continual growth, ebbing and flowing of hair as the torso breathes reflects the dream-like growth and movement of the seen graveside, the grass. Much of my work deals with cycles of various kinds, and the looping nature of the animations support this thematic tendency. The position of the body, lain head to the right, mimics that of the assumed body in the unseen graveside. This links my body’s lasting relationship with my sister, though, my body is no longer the same one she knew.

Follow

Follow