As a newcomer to both Indigenous and media studies, trying to comprehend “screen sovereignty” has been a difficult task. However, scholars such as Dowell have been crucial to cultivating my understanding of the concept. In FNIS 401F, we have also had the great opportunity to explore pieces such as God’s Lake Narrows which I will use in this post to further develop this concept of screen sovereignty.

My understanding of screen sovereignty is when groups that are usually disadvantaged, talked over, and/or ignored by popular media finally have the opportunity to create art in the means that they prefer. This art also has the appropriate means to reach the intended audience. True screen sovereignty derives when there is no concern over how an audience outside of the intended community will react to their work. The piece is created from free will and a desire to share a culture, language, history, etc. that has not traditionally been largely shared.

Dowell (2013) defines visual sovereignty as “… the articulation of Aboriginal peoples’ distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collection [of] identities through aesthetic and cinematic means … [by] producing [their] own images” (p. 2). This is an “act of self determination” (Dowell, 2013, p. 2) that recognizes the Indigenous presence in Canada remains dominantly Euro-Canadian space. This definition of screen sovereignty includes the presence of political dimensions that shift where power is placed, thus making the viewer uncomfortable. This process inverts the gaze of the viewer, forcing them to experience the piece in ways that they aren’t accustomed to. Using these practices, this type of storytelling can become intergenerational, as did the loss of many cultural practices with residential schools. Through the screen, these products can be shown to every generation after the creator is gone, as the history and culture will continue.

Dowell proves her points further by discussing the relationship between the Lower Mainland and screen sovereignty, in addition to her own work. She begins with transition towards an environment that is beginning to embrace Indigenous creativity and thought began in the 1980s with the Chief Dan George Media Training Program at Capilano College. As an employment program that taught basic skills in media production, many of these graduates went on to create Indigenous films. Dowell continues to tell the advancement of Indigenous screen sovereignty with discussion of the Oka Crisis in 1990. She pronounces this event as key inspiration for the Indigenous population to get involved with media, which then irked the creation of the Imagenation Aboriginal Film and Video Festival. When representing the Oka Crisis, and other Indigenous topics, Indigenous storytelling has been taught and evolved as more of a community involved effort than an individual one with most of the recognition of the director. Dowell describes the creation of a new piece as an, “Act of sovereignty to bridge these ruptures and repair Aboriginal social relationships through the process of media production” ( 2013, p. 3). The implementation of Indigenous-specific media training programs has created an ever-growing group of artists, especially in the Lower Mainland in British Columbia. This group has fostered an environment where Indigenous artists can share their thoughts, beliefs, language, or any other part of their lives that they want to share.

Since the 1980s when Indigenous media programs began, several graduates from the program at Capilano and others have created countless pieces to fill the existing gap for Indigenous pieces. Kamala Todd is one of the many of Indigenous artists that is creating art that continues to shift attention and the ownership of space to an Indigenous focus. In her short film, Indigenous Plant Diva https://vimeo.com/115933550 , Todd “write[s] Aboriginal presence onto the land” (Dowell, 2013, p. 14). The purpose of the film is to foster an appreciation for plants and their uses. The film features, ‘T’Uy’Tanat’ Cease Wyss, who shares some of her extensive knowledge of plants, while shots continue of the more urban Vancouver landscape (her blog here). One of the shots showcases plants growing in cracks between buildings that is juxtaposed with the Vancouver city skyline. Dowell asserts that this intersection of knowledge of plants and the urban Vancouver landscape is still at the crux of knowledge of the Squamish peoples. She states that, “This asserts visual sovereignty by articulating the longstanding connection that Coast Salish people have with the land in Vancouver and by repositioning Vancouver as an Aboriginal city” (Dowell, 2013, p.16). Indigenous Plant Diva is one of many pieces that transfers the perspective of the Vancouver from urban city and returns it to the original and rightful owners of the space. Little by little, this increases the influence Indigenous storytellers have. This also alters how they move within some spaces, and how others perceive their movement within this space when Indigenous People have more associations with a particular place.

Importantly, screen sovereignty welcomes projects that puts Indigenous audiences first. This allows artists to primarily produce for their community, which is not difficult in Vancouver as the home of one of the largest Indigenous populations (Dowell, 2013). While their community is the main audience in mind, one of the goals of Indigenous screen sovereignty is to raise awareness of the population and their stories to non-Indigenous viewers.

Next, I’m going to look at God’s Lake Narrows more closely as one example of screen sovereignty.

Though it is not a film, it is still a form of visual art that represents the community of God’s Lake by an individual that grew up there. It is an immersive and unique experience that while is different from a film, it still provides a personal look into the God’s Lake Narrows community. Using the radio from God’s Lake gives a unique insight into the community for outsiders. Here, listeners can hear topics such as calling numbers for bingo and calling for an ATV because someone needs to drive to work.

Earlier in the post, I defined what screen sovereignty can look like. The emphasis is on the freedom to create work meant to resonate strongly with one specific community, but could be shown to those outside the intended space and non-Indigenous people. The God’s Lake Narrows project does this through a range of text, photographs, and audio. God’s Lake Narrows is unique in the way that it is directed for the most part at a non-Indigenous audience. After describing why reserves may seem closed off, Burton says “There are differences between you and I”. He continues to describe the community where he spent the first part of his life. He says “The only people that casually go through God’s Lake are here to fill the White People’s Jobs: nurses, teachers, police, conservation officers”. Since God’s Lake is a place that usually only hosts Indigenous Peoples, it is the to commendation of Indigenous screen sovereignty that this community is represented.

Burton et al. help to form context for specific situations in God’s Lake, with support from visual and audio tools. Burton writes that, “You know this person sacrificed his income for his four-wheeler and you know why his porch door is so worn and torn”. Following this statement is a photo of a house with snow surrounding it and an icy road. From the photo, any viewer can see that it appears to makes sense to own a four wheeler rather than another vehicle. Burton et al. lay out out the process of understanding so it is accessible for all audiences. A four-wheeler makes sense with the snow and to transport yourself and your family from between houses. Visual and audio devices used in the God’s Lake project justifies the reasons for decisions city dwellers would have difficulty understanding, while also humanizing the people that these issues affect.

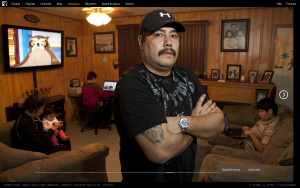

God’s Lake Narrows contributes as an excellent example of a post-colonial production of ideas as “Fourth World cinema” (Dowell, 2013, p. 2) for an Aboriginal audience. In order to do so, they have had to reconfigure the means of production to “… overturn unequal power dynamics to claim their right to self-representation” (Dowell, 2013, p.5). Burton et al. challenge the power dynamics using a photo of a man, presumably in his own home or a family members, looking straight into the camera. The figure of authority in this project is placed onto the subjects of the God’s Lake community; this is a unique circumstance considering the usual influence of those living in reserves. Burton et al. is flipping the norm on its head. Burton assures the audience that though he is aware of the issues in God’s Lake, that “As shitty as it might have been at times, I realize that God’s Lake is the place that has given me distinction in this world”.

With the formation of screen sovereignty, Indigenous stories are no longer being completely overshadowed and pushed aside for more Western-centric media. Accordingly, the implementation of Indigenous media education and the support of a creative community has fostered the creation of projects designed for Indigenous communities. The star of Indigenous Plant Diva, Cease Wyss, tells viewers that “I always know in my heart and my mind that I am connected to this land for many centuries” (Kamala, 2015). Screen sovereignty provides the opportunity to create an inclusive environment for artists to produce art that is able to express any topic and to carry on this information through generations. With continued support and funding, projects such as God’s Lake Narrows and countless others will provide Indigenous communities with high quality work, inspire other Indigenous artists to create art, and continue to educate non-Indigenous communities.

For some information on the current Indigenous Independent Digital Filmmaking program, click here.

References

Burton, K. L., Smith, A., Fellows, C. (2012) God’s Lake Narrows. Retrieved from http://godslake.nfb.ca/#/godslake

Dowell, K. (2013). Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World. Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, pp.1-20.

Kamala, T. (2015, January 4) Indigenous Plant Diva: https://vimeo.com/115933550

Wyss, C. (2014, May 7). Indigenous Plant Diva. Retrieved from: https://indigenousplantdiva.wordpress.com/