Welcome back ENGL 470!

Prompt: Explain why the notion that cultures can be distinguished as either “oral culture” or “written culture” (19) is a mistaken understanding as to how culture works, according to Chamberlin and your reading of Courtney MacNeil’s article “Orality.

The idea that orality is a primitive precursor to written text is a concept that is deeply ingrained in Western thought and society. Through our education systems, we are taught from a young age to value the beneficial advancements brought upon by innovations surrounding written text. From the invention of the first printing press in the early 15th century Europe to the making of the first forms of writing paper during China’s Han dynasty, we are told that the development from orality into written text was vital in the birth and growth of many great nations.

Even in today’s society where our concepts of communication are constantly evolving due to the influence of the World Wide Web, these flawed beliefs still exist. Cultures around the world who still rely on mainly oral forms of communication are often instantaneously labeled as undeveloped, uneducated, subordinate, and impoverished. This is also fuelled by the way certain forms of communication are treated within North America, today, where oral communication is seen as lesser than the ability to read and write, and illiteracy is treated as a problem that plagues the poor and useless. Orality is often framed within this ideology that those without a written text central to their society are not as well off, in need of help, and are part of a statistic that teaches us about realities of poverty in the US and Canada. Furthermore, many respected scholars within the realm of communication support and advocate these same ideas. In Courtney MacNeil’s article on “Orality”, the Toronto School of Communication places alphabetical writing as “absolutely necessary for the development of not only science, but also of history, philosophy… [and] literature…and of any art”.

However, there are undoubtedly many problematic aspects of this way of thinking that frames communication on a hierarchy. As J. Edward Chamberlain points out in his text “If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?”, this way of judging cultures, where orality is always subordinated by the more desirable and respected form of written text, encourages a “blend of condescension and contempt” for those that fail to fit Western and European standards. Furthermore, even when other cultures do have their own forms of “written culture”, they fail to be recognized as legitimate because they do not fit the confines of the syllabic and alphabetical understanding of writing that governs Western society. This binary structure of orality vs. writing thus fosters an incredibly hostile and toxic environment where other cultures and minorities are appropriated to Western and European ideologies of what is significant, what is respected, what is REAL.

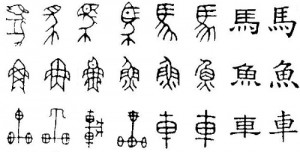

In reality, not only do oral and written forms of communication coexist in their importance, but the defining features of what constitutes as a “written text” are far from limited to Western and European ideals of letters, syllables and alphabets. On page 20 of Chamberlain’s text, he notes that for some so-called “oral cultures”, a written text exists for them but in the form of “woven and beaded belts and blankets…canes and sticks, masks [and] hats and chests”. Moreover, for countries like China that have a very rich and flourishing culture, written text comes in the forms of characters that do not fit the Western standards of a standard alphabet. In fact, many of the original versions of these characters, that have changed from dynasty to dynasty, found their way to be from pictures and stories. Thus, by seeing communication as a hierarchy with rigid rules about what constitutes culture, we are hindering ourselves from the potential benefits of communication that can only happen by seeing spoken word and written text as “mutually interdependent”.

The reality is that “our stories” and our cultures can not flourish successfully from only relying on written text and seeing orality as a thing of the past. Instead, we must realize that all of us are “much more involved in both oral and written traditions than we might think”, and that the hierarchal understanding of the two must be abandoned for us to move forward.

Works Cited

Butler, Chris. “The Invention of the Printing Press and Its Effects.” Flow of History. N.p., 2007. Web. 21 May 2015. </http://www.flowofhistory.com/units/west/11/FC7>.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Finding Common Ground. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2003. Print.

“Invention of Paper in China.” History of China. N.p., 2007. Web 19 May 2015. <http://www.history-of-china.com/han-dynasty/invention-of-paper.html>.

MacNeil, Courtney. “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. N.p., 2007. Web. 21 May 2015. <https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/orality/>.

Olmstead, Gracy. “The Death of Writing & Return of Oral Culture.” The American Conservative. N.p., 2013. Web 20 May 2015. <http://www.theamericanconservative.com/death-writing-oral-culture/>.

Hey Freda! Great idea bringing up all the different cultural interpretations of what literature is. Indeed, I can see someone from an alphabetized writing culture thinking pictographic writing, like characters, as strange, foreign, maybe even antiquated and unsuitable for modern life. And then vice versa thinking for someone raised in a pictographic writing culture.

Your reminder that literature doesn’t have to exist in words but in physical accessories like beads and hats calls to mind things we have today that are not writing, per se, but add to our contemporary cultural narrative as well. What about Tweets, Facebook statuses, Vine videos, and Instagram feeds? Text messages and online rants on fandom forums? Is that stuff literature? Our online materials tell very clear stories about us, yet, I don’t see many universities studying social media “stories” as “serious” forms of literature!

I’m looking around my bedroom right now and, discounting the large piles of books I have here, there are many more things that tell the story of who I am: like musical instruments plastered with stickers, a very messy desk, my highly particular choice of pens… Indeed, many things can be interpreted as literature, depending on how wide we define it of course. Is literature anything that tells a story, relays an experience? Where do we draw the line of what is literature and what is just “stuff”? Or just “communication”? I’m interested to hear what you think literature *is*, at the end of the day. Maybe if we work harder to define what is literature instead of what is superior and inferior forms of *relaying* literature (oral vs. written), we can take a major step towards accepting all forms of literature communication.

I too felt this was a solid post in its combination of ideas from both Chamberlin and MacNeil’s text. I thought I’d add to the discussion of non-alphabetic writing by bringing up Chamberlin’s mention of the “quirt” which told stories of ancient raids (178). What I think is most interesting about this form of literature is that it is much less dictatorial than what I am used to working with in English. As an English major, I suppose I deal in drawing different and sometimes competing readings out of a single text, so I’m not saying that our language is not malleable, but this pictographic language seems to be much more inviting. A word feels more final than a picture.

What’s also interesting is how the ethnographer, with his academic mindset, reads the quirt as fact, whereas the Kainai elder, Frank Weaselhead, recognizes the story told on the quirt as a recounted dream. This sort of discrepancy is perfect for Chamberlin’s approach because it privileges interpretation over fact. The writing on the quirt opens discussion rather than closes it.

Hi Hayden!

Thank you for mentioning the idea of “quirt” from Chamberlain’s text. I agree that its a perfect example of the importance of interpretation over seeing things as black and white / “fact”. It is this unbiased, more open view of culture and story that will help further our discussions rather than hold us back, and we need more of it!

🙂

Hi Charmaine!

Thanks for replying. And yes, I love what you had to say about all the things that contribute to your identity and your story. It goes beyond things that can be written down and I think that is what MacNeil is trying to get across in her article. Perhaps the point to take home is that literature is whatever helps one tell their story, and that is up to each individual and culture. Listening to rankings by scholars halfway across the world, no matter how renowned, doesn’t contribute much if they aren’t living and experiencing that particular culture themselves. Everyone has a story, and it can be told in more ways than one!

🙂