“9. King’s “preoccupation with mapping” (Goldman) is interrelated with the constant returning to Fort Marion. For the Women who fall from the sky, all roads lead to Fort Marion. Goldman suggests that King selected this episode in history because the Ledger Art of the Fort Marion Indians consists of “drawings [that are] acts of Native self-representation” (26). With this in mind, discuss why all roads lead back to Fort Marion in the novel, and be sure to consider the possible parallels between Dr. Hovaugh’s fictional institution in Florida and the historical Fort Marion.”

(Paterson, “Lesson 3.2”)

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, Nam June Paik (1995)

Reading this book was a trip, in every sense of the word. The closest books that I have read that come close to a similar unconventional boundary bending, literary convention squashing style are Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler and, to a lesser extent, Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. That being said, Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water is a very different book than either of the aforementioned. Through his literary project, King is telling a story that I view as more politically minded (for lack of a better word) than either Calvino’s or Haddon’s novels.

But these comparisons are beyond the point of this post, which is: why choose Fort Marion as the final destination of the supernatural, and (literally) down to earth, women of King’s novel?

Marlene Goldman, in her article “Mapping and Dreaming: Native Resistance in Green Grass, Running Water“, notes that Thomas King could have chosen any one of many historical events that highlighted a conflict between the settlers and Natives. So – why Fort Marion circa 1875? Goldman writes:

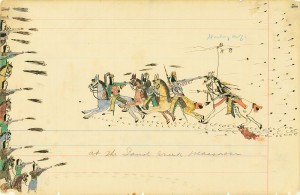

“King may have chosen this incident because it draws specific attention to Native acts of self-representation and to the status of the book…the Fort Marion episode reflexively addresses what it means for Native people to disseminate artistic representations of tribal life in the overarching context of widespread domination by the settler-invader society…” (emphasis added, 24)

King is very consciously presenting his book as a work of Native self-representation. Not only its it a work of representation but it is also a challenge to a domineering culture that obliterates by incorporation. King’s use of this culture’s own tools to reshape expectations is confusing, but effective. He is creating his story in part by using the fabric of a shared knowledge of the Western canon common to most of his readers, only this fabric is getting unravelled, rewoven and patterned out to create a garment at once recognizable, but fundamentally different. This forces readers familiar with these canonical stories to re-evaluate them. He does this with history too, peppering the narrative with notable historical figures significant to settle-colonial expansion, drawing them in a way which promotes critical consideration.

The Western canon is a sort of framework for the reproduction of Western culture – consider the books read in high school Language Arts classes, and the pervasiveness of Biblical tropes in literature. This canon was imposed, through systems of education, on all Canadians, and significantly on First Nations people via the Residential School Act.

At the Sand Creek Massacre, Howling Wolf (1874-1875)

All roads in the novel lead to Fort Marion, and this narrative structure is perhaps used as cautionary tale by the author – history is doomed to repeat itself. I think King chooses this structure in part to illustrate that genocide and displays of dominance were an probable result of these two cultures and worldviews meeting, but that what happens after is less certain. Repression is uncertain, and Indigenous culture has a way of surviving. The prisoners of Fort Marion, entrenched within a bastion of settler-colonial power, use the tools available to them to create representations of their culture, and this action serves as touchstone for the narrative in King’s story. This act of establishing representation, in the face of annihilation (even within Fort Marion, missionaries were trying very hard to convert the prisoners), is what King finds significant.

Concerning Fort Marion and its echo, Dr. Hovaugh’s institution, there are many parallels worth considering. As institutions containing and controlling First Nations people, they serve as tools of the settler-colonial nation-state. Both locations form a thematic map for the narrative – Fort Marion as repeat sign and the office of Dr. Hovaugh’s institution as bookmarks to the journey.

Noting the connection between Dr. Hovaugh and Northrop Frye and thus the positioning of Institution and its garden as the ‘Bush Garden’, I think King uses the Institution as metaphor within his story to connect it to the conventional understanding of what a novel is by evoking Frye and his literary criticism. Also, Dr. Hovaugh starts and finishes the story unchanged, in his office, looking out at the garden and asking for John. There is an inevitableness to Dr. Hovaugh’s fate, similar to the inevitableness of ending up at Fort Marion.

Blanca Chester writes – in an article examining Green Grass Running Water – that “Frye’s structuralist theory reveals a closed system…Hovaugh’s mystical and reclusive retreat to his mythical garden also suggests his own escape into timelessness, into a world of his own mythic making…” (52). This God-complex is challenged throughout the novel, and playfully (thought ominously) in the closing pages:

“Well, it’s good to have you back,” said Babo. “Dr. Hovaugh was very concerned about you.”

“That’s nice,” said Hawkeye. “Maybe next time, we’ll help him.”

“What a wonderful idea,” said Babo. “I think he’d like that.”

“We could start in the garden,” said the Lone Ranger.

Babo smiled and rubbed her shoulder. “Now wouldn’t that be the trick,” she said. “Wouldn’t that just be the trick.”

(King, 427-8)

Works Cited

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, Toronto: 2010. Print.

Hi Merriam

I really enjoyed reading your blog post. You’ve obviously done your research and “At the Sand Creek Massacre” illustration (which I assume is from Fort Marion?) was a brilliant touch. Until you mentioned it, I had not thought of Dr. Hovaugh as a static character whose own immutability illustrates Northrop Frye’s idea of a closed system. How do you think the Medicine Wheel plays into this? The creation tales of the four Indians is essentially the same story repeated four times. In your opinion, does circularity reinforce or present an alternative to the circles that Joe Hovaugh both draws and enacts? I look forward to hearing your thoughts!

Thanks again,

Bea

*Does this circularity*

In my opinion, the circles are presented as alternatives. The circles that Dr. Hovaugh draws and enacts are circles of confinement and serve as parameters of precision. The repetition creation tales of the four Indians are circular in the style of the ‘circle of life’ (for lack of a better descriptor): cyclical in the way life is a repetitive cycle of birth -> growth -> old age -> death -> birth (as symbolized in the medicine wheel). The medicine wheel is a just that – a wheel – it turns, without ever being confined to one of its sections…it cycles through.

You’ve given me a lot to think about here! I guess I see Dr. Hovaugh’s ‘circles’ as being static, and the medicine wheel as being a dynamic circle.

Hi Merriam,

I agree, the reading of this novel was very intriguing. I’ve also learned so much from my fellow students this week. I found a number of this weeks post questions out of my grasp, I was just unable to wrap my head around them. That being said, I have learned so much from reading your post. The link leading to Words and Names gave me great insight into some of the historical figures mentioned in the book.

Thanks for a great post,

Danielle

Hi Danielle,

Thank you for you comment! I agree with you, in that this novel – and the subsequent discussions and observations inspired by it – is a dizzying one to contemplate! I have difficulty as well trying to consider all aspects of this novel, and its far reaching cultural, historical and political cross-referencing, and then tying all that to a renewed look at First Nations construction and identity (I’ve found turning to scholarly sources IMMENSELY helpful on that front! Check out Brian Johnson’s Plastic Shaman in the Global Village: Understanding Media in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water”“, and Blanca Chester’s “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel).