Both Barthes’ “The Death of the Author” and Foucault’s “What Is an Author” are very stimulating, insightful texts that do exactly what Dr. Freilick identified as one of the primary goals of this course – they make us question our assumptions. I strongly believe that this is a foundational exercise of our education and I have always been an avid proponent of the practice of sharply questioning what you believe and what you know.

Having said that, when it comes to soundly convincing me, both of these texts – considered either individually or in conjunction – have a limited effect. I have been exposed to them before in English Lit courses and I made a conscious effort to approach the texts open-mindedly, trying to erase my memories of the fact that they did not sway me in the past either, as it has now been a few years since Intro to Literary Analysis in my English major and consequently more exposure to literature, both of the English and Hispanic worlds. However, I find myself somewhat at odds with some of the arguments that the texts put forth. I agree that the author is a product of society, and I definitely do not believe in seeking the “explanation of a work in the man or woman who produced it” (Barthes 143) – as I believe that that is a very dangerous and pointless trap, as we were discussing in class during out last meeting. This is also certainly a very tempting path to take; I have found myself forcing an interpretation on a text because of socio-historic and biographical information that we have the privilege of knowing about the author – and I have to at times actively stop myself from doing this.

However, I do not believe that we have yet reached – and I wonder if we ever will – the point at which language can ‘act’ and ‘perform’ in a completely empty vacuum. As Barthes points out, Surrealism did indeed contribute to a desacrilization of the Author through its characteristic ‘jolt’, the practice of automatic writing, and the principle and experience of several individuals writing together, yet can Surrealism ever be fully separated from André Breton, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel (yes, I do choose to see them as ‘authors’)? In my opinion, to do so would be to also bring about a loss – while we must take every caution to not let historical and biographical information overshadow and control our view of a work, I believe that it can enrich it. A piece of literature can certainly stand independent of its socio-political context, but is it not also true that grasping this context might also be beneficial? I believe that this is particularly true in texts that share an intrinsic link to moments in history and political movements – for example, as I am conducting my thesis research on the Spanish Civil War, I cannot imagine getting a holistic picture of the literary texts (and films) that I am analyzing without having first understood the historical context of the times. When it comes to Barthes’ argument that once the Author is removed, “the claim to decipher a text becomes futile” (147), I am also not sure I agree – one can certainly parse a text and engage in an exercise of ‘interpretation’ without working in the dimension of the Author.

One portion of Barthes’ argument that I very much admire, however, is his concluding call for making the reader “the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost” (148) and his proposition that the unity of a text lies “not in its origin but in its destination” (148). I think this highly crucial to the practice of reading, but I am just not convinced that it absolutely has to come at the expense of the death of the Author; is there no space for the co-existence of both the birth of the reader and the death of the Author? Undoubtedly such an argument does not pack the rhetorical punch of setting up a ‘life/death’ dichotomy as Barthes unequivocally does in the closing sentence of “The Death of the Author,” but I believe that this is much closer to where the field stands at this time – in my personal experience at UBC.

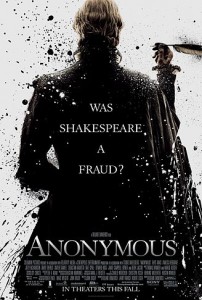

To answer Beckett’s question, I do believe that it does matter who is speaking, and while the work may possess “the right to kill, to be its author’s murderer, as in the cases of Flaubert, Proust, and Kafka” (Foucault 102), I don’t believe that it has. As we have the advantage of time and hindsight (only up to the present date, of course), we can ask ourselves if “as our society change[d], the author function will disappear” (119). Have we “no longer hear[d] the questions that have been rehashed for so long: Who really spoke? Is it really he and not someone else? With what authenticity and originality […]” (119)? I would venture to answer that on the contrary, these are questions that still very much continue to dominate our contemporary literary discourse – just one example would be the relatively recently released film Anonymous (2011) (the film essentially presents the possibility that Shakespeare did not actually write any of the works that are attributed to him). Any B.A. student at UBC who wants to obtain an English Lit major must meet the requirement of taking a 3 credit course focused on either Chaucer, Milton or Shakespeare – bringing to mind the infamous ‘cannon’ debate. However, what is most important thing to keep in mind is not the obligations of an English Lit degree, but whether or not this is a damaging thing to inflict on students, a negatively-impacting the-Author-is-very-much-alive type of view – and to that, my answer is a resounding ‘no’.

To answer Beckett’s question, I do believe that it does matter who is speaking, and while the work may possess “the right to kill, to be its author’s murderer, as in the cases of Flaubert, Proust, and Kafka” (Foucault 102), I don’t believe that it has. As we have the advantage of time and hindsight (only up to the present date, of course), we can ask ourselves if “as our society change[d], the author function will disappear” (119). Have we “no longer hear[d] the questions that have been rehashed for so long: Who really spoke? Is it really he and not someone else? With what authenticity and originality […]” (119)? I would venture to answer that on the contrary, these are questions that still very much continue to dominate our contemporary literary discourse – just one example would be the relatively recently released film Anonymous (2011) (the film essentially presents the possibility that Shakespeare did not actually write any of the works that are attributed to him). Any B.A. student at UBC who wants to obtain an English Lit major must meet the requirement of taking a 3 credit course focused on either Chaucer, Milton or Shakespeare – bringing to mind the infamous ‘cannon’ debate. However, what is most important thing to keep in mind is not the obligations of an English Lit degree, but whether or not this is a damaging thing to inflict on students, a negatively-impacting the-Author-is-very-much-alive type of view – and to that, my answer is a resounding ‘no’.

In order to achieve a cohesive understanding of our assumptions, we cannot push aside questions of “What are the modes of existence of this discourse? Where has it been used, how can it circulate, and who can appropriate it for himself? What are the places in it where there is room for possible subjects? Who can assume these various subject functions?” (120). these are the fundamental questions to the practice of questioning assumptions and sharply analyzing and also questioning the world around us – and my argument is that the birth of the reader does not have to come at the expense of the death of the author; an in-between space is indeed possible, and I believe that this is what we achieve in the literature classes that make up the Master’s and PhD programs that we are currently enrolled in.

Yes, I agree: let him or her alive! The birth of the reader doesn’t implies the death of the author. On the contrary, I think both entities could be constructive for each other. For instance, having some information about the author could help to understand better his or her work. At the same time, I think that when an author realize that he has an audience, he could get from them important feedback and improve his work. So, I believe in a symbiotic relation between these two entities rather than the death of one of them. The “father” doesn’t have to die in order to give his “son” a life. The last one will create his own relation with the readers, and they will decide if they need or not the reference of the author.

By the way, that movie looks very interesting! I heard some years ago that theory, but I didn’t know it was so important that could inspire a movie.