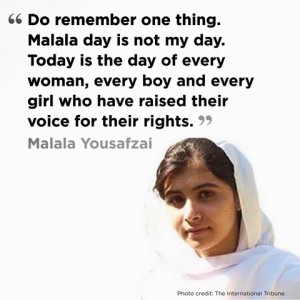

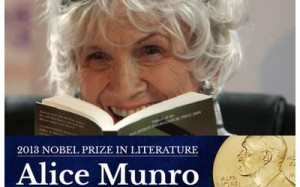

It seems especially fitting that our feminism week of readings falls at a time when some of the main news headlines are the one year anniversary of sixteen year old Malala Yousafzai’s shooting at the hands of the Taliban in Swat Valley in Pakistan (She was targeted for going to school, something the Taliban does not believe girls should do and also because of her family’s outspoken opinions on the importance of girls’ education – her dad was the head of the school that she attended. Just this week, the Taliban issued a new threat saying they will kill her. More information and different links can be found on her Wiki page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malala_Yousafzai) and Alice Munro being the first Canadian woman to win a Nobel prize in literature (she is the first Canadian citizen and only the 13th woman to win the award; here is a link to her first post-award interview: http://m.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/nobel-prize-win-was-totally-unexpected-alice-munro-says/article14850233/?service=mobile#!/

The line most pertinent of our readings this week is also my personal favourite line in the whole article: “[The local paper] called [Munro] a “shy housewife,” [her husband] recalled, and “boy was she ever mad”. It was also interesting that Mr. James Munro identified her as a “feminist before feminism was invented”).

I thought the readings that we were assigned provided a great overview of a complex and fluid phenomenon. As all of our readings underlined, ‘feminism’ is cannot be wholly encapsulated by a single definition or categorization. Hélène Cixous describes gender representation as an oppositional tradition in which women are portrayed as secondary to male rationalist principles and she argues that both men and women can take up the practice of what she calls ‘feminine writing’, while Gayle Rubin provides what I find to be an extremely helpful explanation of the points of both connection and dissonance to the principles outlined by Marx, Engels and psychoanalytic theory, all the while arguing for us to push these theories further, define them more precisely, and pick up where they left off. Luce Irigaray focuses on the subordination of the feminine within the discourse of power by discussing the masculine idealizing tendency “that uses the feminine as a mirror for its own narcissistic speculations” (795), while Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar focus specifically on taking a look at the literary canon and argue that the majority of images of women in literature are really reflections of “negative energies and desires on the part of male writers” (812). Audre Lorde challenges the often cited homogeneity of women’s experience by stating the necessity of also taking into account “differences of race, sexual preferences, class and age” (855). She explains that it is not only a room of one’s own (in Virginia Woolf’s defense, financial independence for women and having the means to support yourself was a huge part of her argument as well) that a woman needs in order to produce fiction, but also “reams of paper, a typewriter, and plenty of time” (855). Lorde also keenly underscores that differences between African-American women are being misnamed and used to separate the members of the community for one another, a practice that she identifies as a danger that must stop. Geraldine Heng provides a focus on the movement of liberation of women in Third World contexts, and she makes the poignant argument that feminist movements in the Third World have “almost always grown out of the same historical soil, and at a similar historical movement, as nationalism” (862). Heng also specifies that it is “a truism that nationalist movements have historically supported women’s issues as part of a process of social inclusion, in order to yoke the mass energy of as many community groups as possible to the nationalism cause (as cited in Anderson 1983). This wide variation speaks to me of the fluidity of the movement and of the need that it constantly has to adapt to political and social circumstances – and I don’t believe that this is a need that belongs only to feminism; I rather believe that this is the principal technique that a movement manages to stay relevant and useful; this grassroots connection to the ones it aims to empower is absolutely crucial in my opinion.