Lagos’ housing crisis is a top concern for residents of the city and the hundreds of thousands of migrants who flock to the city each year in search of upward mobility. Solutions are being generated either formally by city planners and state sanctioned development or informally by innovative individuals with the motivation to make housing work.

We detail two developments in Lagos taking different approaches to housing and urban growth – both using the ocean as a basis for residential space. As NLE architect Kunle Adeyemi remarks, “Eko Atlantic is about fighting the water; [here in Makoko] we’re saying – live in the water!” (Ogunlesi, 2016). The following will explore how each neighbourhood plans to address community development in the wake of a housing crisis.

Makoko: Waterfront informality or development model?

From fishing village to squatter settlement

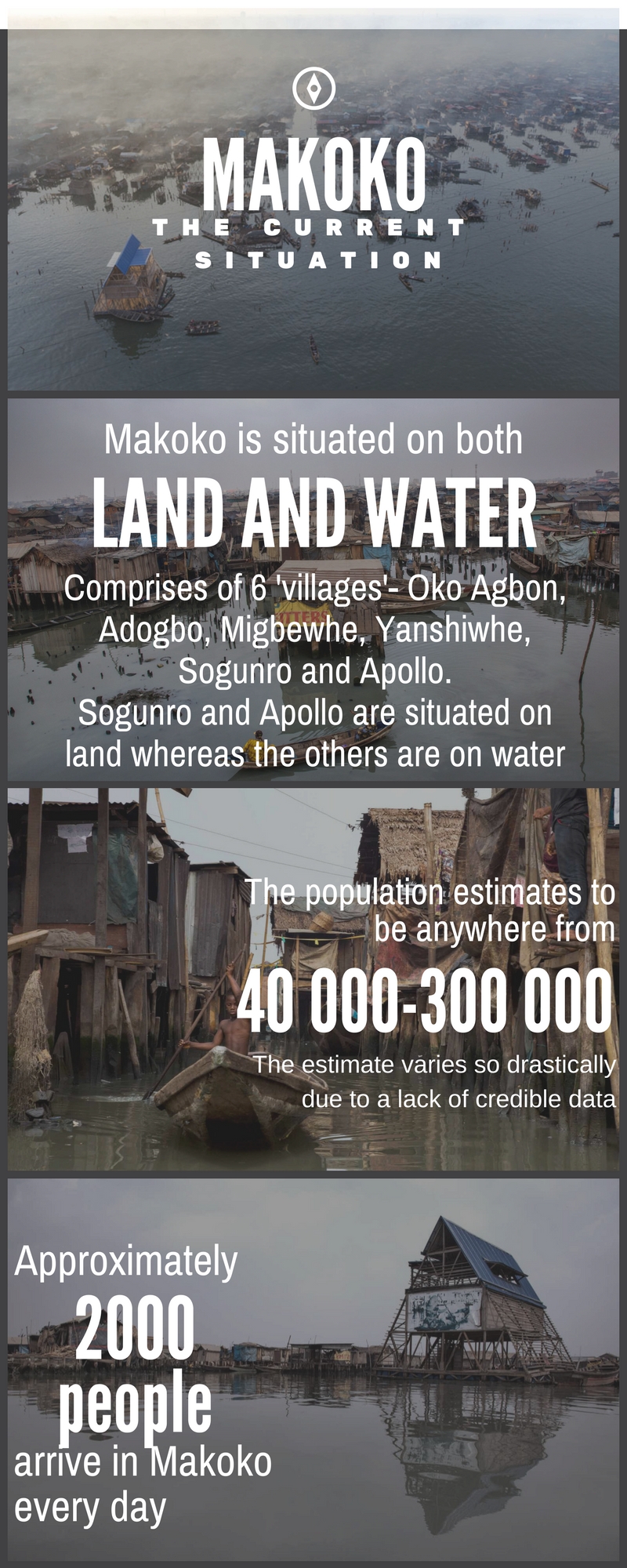

Situated along Lagos’ dense, urban coastline and visible from the main throughway is Makoko, a 200-year-old fishing village-turned-squatter settlement. Makoko originated on land, but as inner city property increased in value, residents of Makoko were forced to build informal housing on stilts and expand outwards into the lagoon. For years, fishing has been a major source of income, but other informal sector activities such as construction and sand dredging have emerged as common means of living for the urban poor (Ogunlesi, 2016). As mentioned above, figures on Makoko are elusive, with estimates of 40,000 to 300,000 people. With a growth rate of 7.5% per annum (Riise & Adeyemi, 2015) and a lack of proper infrastructure, considerably hard questions face Makoko: how will it provide basic, secure services to its ever-increasing population, especially medical services and stable building structures? How will the village defend itself against the effects of rising sea levels, given its precarious build? And how will the government be convinced to not demolish it?

Demolitions & Aftermath

In July 2012, a government-led eviction left thousands of people homeless. Men on speedboats wielding machetes drove through the waterways demolishing houses. The eviction ended when a Makoko resident, Timothy Hunpoyanwha, was shot dead by a police officer (AlJazeera, 2012). Although the government stopped the eviction, they had made their scheme known; Makoko lies close to the city centre, and in order to “restore the amenity and value of the waterfront,” the entire community would have to be cleared. Lateef Raji, advisor to the state governor, claims that “no reasonable society…would allow its citizens to live the way they are living” (AlJazeera, 2012).

Route to re-investment?

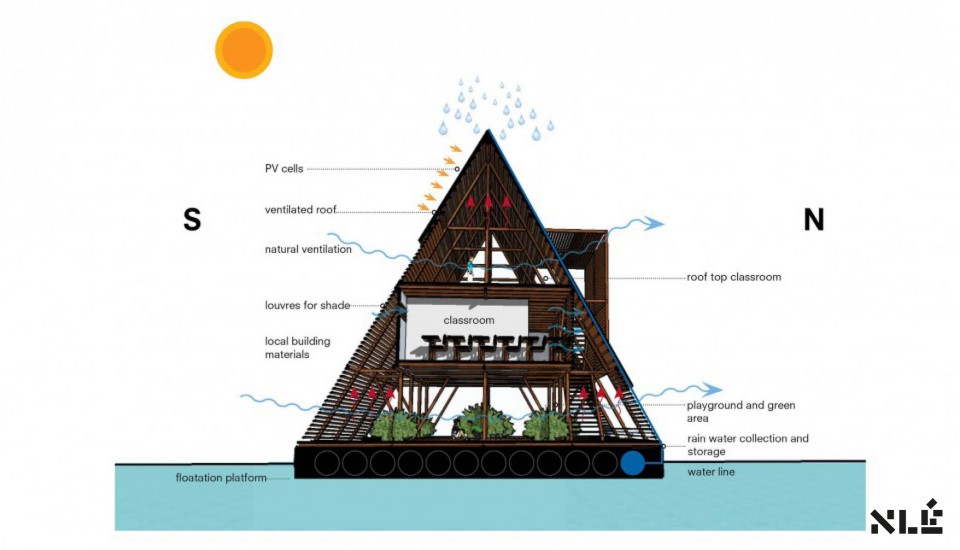

The demolitions attracted the attention of several urban design firms-NLE Architects and Urban Spaces Innovation- who proposed sustainable models of community growth for Makoko instead of its demise. Architect Kunle Adeyemi designed the Makoko floating school; a socio-technological advance that simultaneously upgrades local infrastructure and retains the characteristic features of the community. The school is accessible by boat and was built using exclusively local building materials. It collects rainwater and is retrofitted with photovoltaic cells for solar energy production.

After extensive coordination with the “Baale”, or governor of Makoko, the floating school was operationalized in 2015; quickly becoming the focal point of the village. In 2013, an urban design firm and several local NGOs, including the advocacy group SERAC, collaborated in drafting the “Makoko/Iwaya Waterfront Regeneration Plan” , submitting it to the State Planning Department. The plan emphasizes upgrades through community-based cooperation, economic empowerment, and better infrastructure (Buckminster Fuller Institute, 2014). It looks to increase tourism, provide secure, legal housing that isn’t at risk of flooding, and add green space, among other service provisions. This pioneering vision of urban growth is promising to Makoko residents and could serve as a template for sustainable growth in surrounding slums. The caveat: the floating school prototype collapsed due to wear and tear in 2016, leaving residents anxious that the destruction of Makoko’s most promising development would threaten their future. There may be possibility of an impatient government deciding to proceed with eviction and demolition.

Eko Atlantic: Displacing water in wake of big business and luxe living

Amidst a housing crisis, any major development is newsworthy. Eko Atlantic is not merely a major development; it is nothing short of astronomical.

Why Eko Atlantic

The coast of Victoria Island and Bar Beach have been susceptible to erosion and flooding since the offshore shoal was demolished to allow large ships into Lagos and promote international trade. The breakwater currently in place is undersized and does not provide adequate protection against storm surges and gradual erosion. Therefore, it was necessary for Lagos to rebuild a better barrier to protect the future of the city.

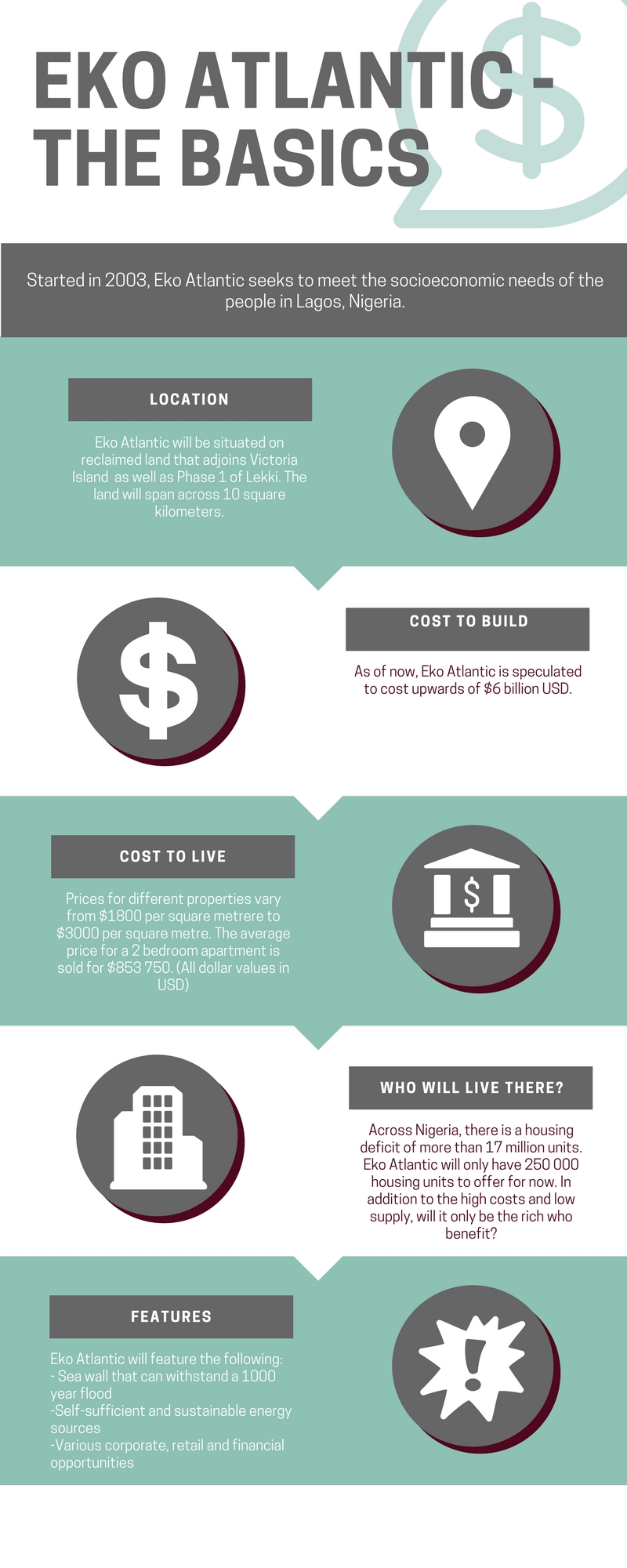

What is Eko Atlantic?

Within the new breakwater, there is a massive opportunity to reclaim land. South Energyx is a major development contractor who took on the bid to build the breakwater – known as the “Great Wall of Lagos” – and dredge and drain the extra area it protects. The urban planners of Lagos see this new reclaimed land as an opportunity to build a well planned, efficient, and attractive city right next to the economic capital of the country. Private companies can purchase lots to develop and build into office spaces, hotels, retail centers, and residences.

Who is Funding Eko Atlantic?

South Energyx, a member of the Chagoury group is solely funding the construction of the sea wall and the land reclamation. They plan to make money by selling parcels of land to private companies for development.

What Lagos Expects

There are regions planned for residences, tourism, as well as financial and commercial activities. The city is expected to house 250,000 residents and provide over 150,000 jobs (Phillips, 2014). The anticipation is that this will promote Nigeria as a shining center for foreign investment and economic stimulation. Additionally, the development will provide housing for the city’s elite and professional (alleviating some of the housing strain), and also attract wealthy expatriates to Lagos.

Sources:

Al Jazeera (2012). Nigeria forces thousands from floating slum. [online] Available at http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2012/07/201272954130169461.html

Buckminster Fuller Institute (2014). Makoko/Iyawa Waterfront Regeneration Plan. [online] Available at https://www.bfi.org/ideaindex/projects/2014/makokoiwaya-waterfront-regeneration-plan

Eko Atlantic (2017). About Eko Atlantic [online] Available at http://www.ekoatlantic.com/about-us/

Eko Atlantic (2014). Eko Atlantic General Progress – November 2014. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuhNrNxuBXE

Ogunlesi, T. (2016). Inside Makoko: danger and ingenuity in the world’s biggest floating slum. [online] The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/23/makoko-lagos-danger-ingenuity-floating-slum

Philips, A. (2014). African Urbanization. Harvard International Review, 35(3), Webpage. Available at http://hir.harvard.edu/african-urbanization/

Riise, J., & Adeyemi, K. (2015). Case study: Makoko floating school. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 13, 58-60. Available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877343515000159

Ventures Africa (2012). Eko Atlantic City: A mammoth new development on the coastline of Lagos. [online] Available at http://venturesafrica.com/eko-atlantic-city-a-mammoth-new-development-on-the-coastline-of-lagos/

Reference for Infographics:

Magdaleno, J. (2013). High-Tech Floating Houses Planned For Nigeria Water Communities. [online] Creators. Available at https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/nigeria-lagos-water-communities-look-like-waterworld

Ogunlesi, T. (2016). Inside Makoko: danger and ingenuity in the world’s biggest floating slum. [online] The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/23/makoko-lagos-danger-ingenuity-floating-slum

Okpamen, E. (2015). Two years after ground breaking, the $6bn Eko Atlantic City is gradually taking shape. [online] Ventures Africa. Available at http://venturesafrica.com/two-years-after-ground-breaking-the-6bn-eko-atlantic-city-is-gradually-taking-shape/

Uwaegbulam, C. (2015). Lead Story Low supply, demand in Eko Atlantic scheme drive land prices higher. [online] Eko Atlantic. Available at http://www.ekoatlantic.com/latestnews/lead-story-low-supply-demand-eko-atlantic-scheme-drive-land-prices-higher/