Environmental Sustainability

Williams Lake has a rich environmental history which supports a diverse and unique ecosystem, is essential for the region’s economy, and is culturally significant for both the First Nations people who have lived off the land for millenia as well as for the post-settlement population who know calls the Cariboo-Chilcotin home. Preserving and supporting a sustainable environment in Williams Lake and the surrounding area will mitigate the harmful impacts of resource extraction (e.g. 2014 Mount Polley Mine Disaster), support new and emerging businesses such as tourism, recreation and green initiatives, and help improve relations with First Nations communities. To this end, in their Integrated Community Sustainability Plan, the City of Williams Lake has identified food security and promoting local food, protecting cherished ecosystems, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions as sustainability issues to prioritize.

A walking path in Scout Island Nature Center

Geological Setting

Williams Lake is located on the Intermontane morphogeological belt. It is bounded to the west by the Coast Belt (which includes the Coast and Cascade Mountains) and to the East by the Omineca Belt (which includes the Monashee, Cariboo, and Omineca Mountains). The topography around Williams Lake reflects the combined influence of post-orogenic extensional tectonics (the flat, undulating terrain) and uplift (deeply incised rivers) as well as extensive Quaternary glaciation (geomorphic evidence of glacial lakes, depositional landforms, and icesheet erosional landforms).

Around 180 million years ago, tectonic plates pushed volcanic mountain chains and ocean floor together to uplift the interior plateau as a jumbled heap of mixed-origin terranes (contributing the few sedimentary and metamorphic rocks you can see in the bedrock topography map below). More recently (as recently as 1 million years ago), large eruptions of flood basalt (hot, relatively non-explosive lava) blanketed this jumble of ancient origin bedrock with thick layers of basaltic lava, smoothing out the topography with a thick cap of flat basalt layers.

If you look at the bedrock geology map below, you will notice some older sedimentary origin rock (in green), and extensive igneous and volcanic origin rock (in red). Click on the red shapes and you will notice that most and the largest sedimentary groups are relatively recent basalt deposits from this period of basaltic flood eruption. (map data source)

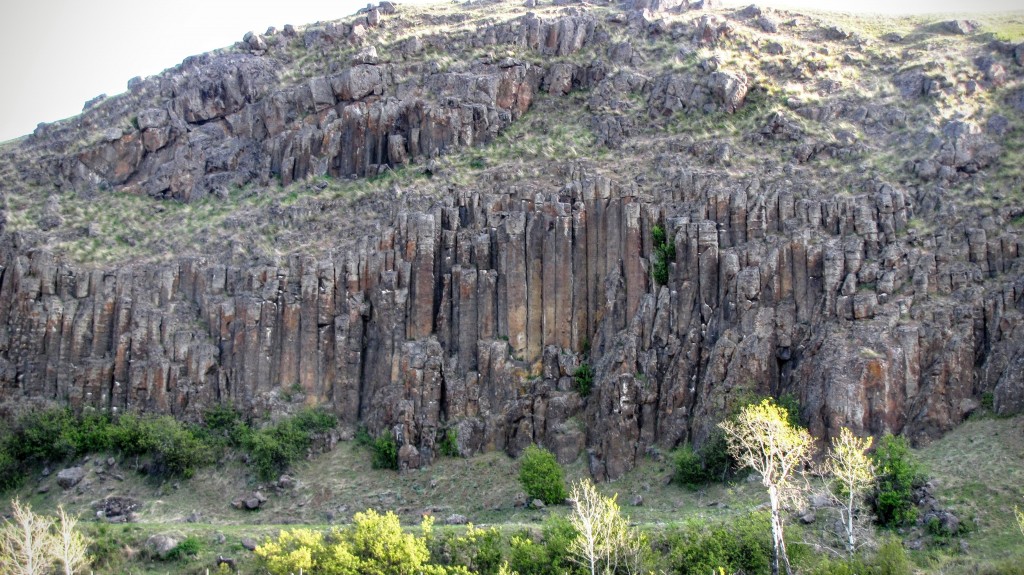

Anywhere where the bedrock topography is exposed around Williams Lake you will notice this thick layer of basalt capping the underlying geology.

Driving through the Fraser Canyon you can see the valley walls capped with beautifully defined basaltic flood layers.

While the basaltic eruptions were beginning to peter out, a new geomorphic agent was beginning to shape the interior plateau. For the last 2.4 million years, the plateau has cycled through numerous glacial and interglacial period, and the erosive and depositional impacts of this ice dominates the landscape today. Superimposed on top of the underlying (often basaltic) bedrock, glacial till and associated deposits blanket the landscape. The river valleys were backed up by ice dams and infilled with sediment through which the river is now downcutting once again. Everywhere you look you will see the geomorphic evidence of the most recent glacial advance.

Glacial Till in Churn Creek Provincial Park. If you see large deposits of unsorted sediment, you are likely looking at sediment that was deposited by ice during the most recent glacial advance.

In an impressive example of an erosional landform resulting from glaciation, a massive flood from a receding glacier carved Chasm Provincial Park out of the bedrock. The cap of basalt is clearly evident at this location.

The Fraser river cuts through glacial deposits in Churn Creek Provincial Park. Were it not for the glacial cycles this canyon might look more like the Grand Canyon, cutting through bedrock.

Ecological Setting

Williams Lake is located in the Interior Douglas Fir (IDF) biogeoclimatic zone, but is surrounded by a number of ecological areas (see the embedded map - data source). The other dominant zones are sub-boreal spruce and pine, and a unique bunchgrass ecosystem dominates in the drier, hotter Fraser Canyon. The Cariboo region supports a wide range of flora and fauna, with 26 BC Red Listed species including the American Badger, Caribou, White Pelicans and the Peregrine Falcon.

Douglas Fir is the dominant tree species and is interspersed with lodgepole pine and a ground cover of pinegrass. The IDF zone is uncommon in BC and is characterized by having Douglas-fir trees aged 1->400 all in the same area. The older, thick-barked Douglas-fir regularly survived frequent (10-20 year), low intensity fires prior to fire suppression activities in the province. In the absence of these fires, fuel loads have built such that the risk of catastrophic fire is much greater now than before the 1900s. Fire and the impact of the previous mountain pine beetle epidemic (which ended in 2007) have significantly affected lodgepole pine and timber activity around Williams Lake. Forest fire suppression and a warming climate increase the severity of mountain pine beetle infestations. Naturally occurring insects and disease such as bark beetles and spruce budworm cause ongoing forest disturbance. Luckily for Williams Lake, the variety of biogeoclimatic zones across the Timber Supply Area provides a wide range of tree species that are expected to buoy the forest industry sector to some degree until mountain pine beetle-affected forests grow back.

Sap oozes out from a hole made by a mountain pine beetle on a lodgepole pine tree.

Climatological Setting

Williams Lake is located in the rainshadow of the Coast Mountains and in the Interior Douglas Fir biogeoclimatic zone, which means that it is quite warm and dry. For the most recent climate normal period (1981-2010), the average monthly temperature ranged between -7.3ºC in the winter and 16 ºC in the summer. Precipitation totalled an average of 451mm per year, ranging from 59mm during the wettest month (June) to 18mm in the driest (March).

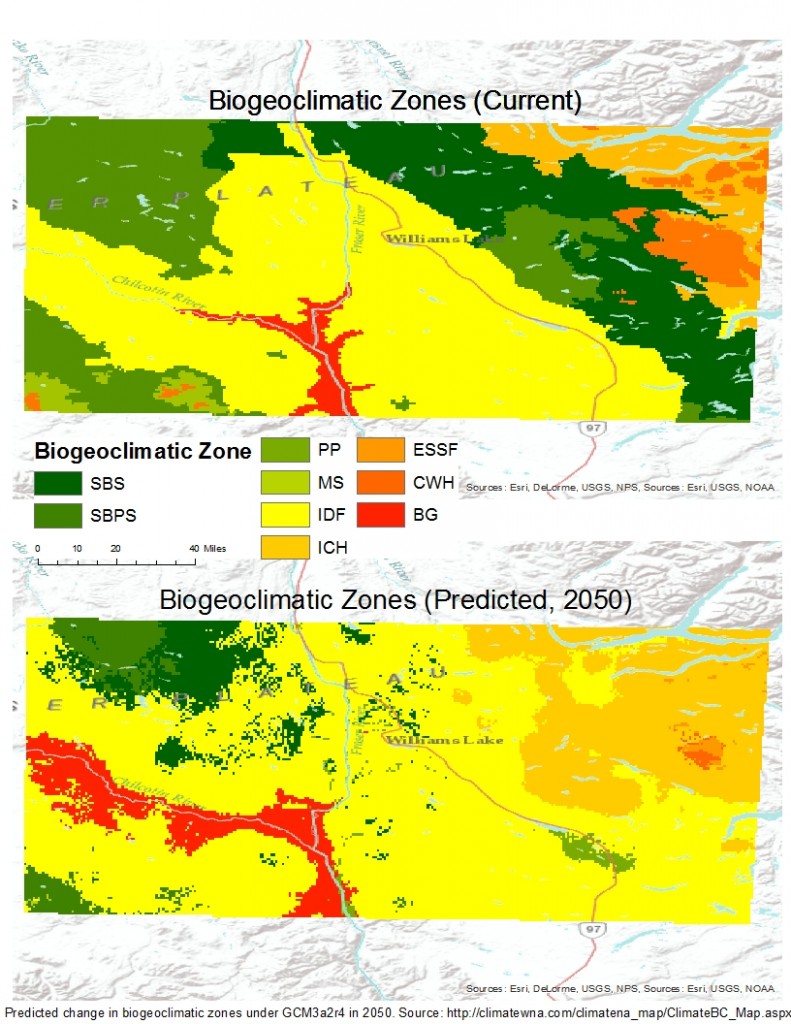

Climate change is likely to hit Williams Lake hard. Rising temperatures and decreasing precipitation is going to lead to a large shift in the dominant ecosystems in and around the city. An interactive map of the impacts of climate change on precipitation, climate, and vegetation distribution can be found here. The possible impacts of climate change on the Williams Lake in 2050 area are summarized in the maps below. A warmer, drier climate may lead to substantial growth of the Bunchgrass, Interior Douglass Fir, Englemann Spruce/Subalpine Fir biogeoclimatic zones, at the expense of the overall diversity.

SBS: Sub-Boreal Spruce SBPS: Sub-Boreal Pine and Spruce PP: Ponderosa Pine MS: Montane Spruce IDF: Interior Douglas Fir ICH: Interior Cedar Hemlock ESSF: Englemann Spruce and Sub-alpine fir CWH: Coastal Western Hemlock BG: Bunchgrass

The bunchgrass ecosystem of the Fraser Canyon. Although it is now heavily degraded by grazing, it stands to benefit from the warmer, drier climate of the future, at the expense of other ecosystems.

Useful Resources

- Mount Polley Mine Spill: a tailing pond breach in 2014 highlighted some serious issues with resource extraction in the region and inflamed tempers on both sides of the issue

- Integrated Community Sustainability Plan – Protecting Cherished Ecosystems

- Endangered species around Williams Lake: a total of 131 species at risk in the Williams Lake municipality, including 27 BC Red List species and 4 COSEWIC Endangered species

- Scout Island Nature Centre

- Local Green News

- Puddle Produce Urban Farms

- Williams Lake 2013 Receiving Environmental Monitoring Report

- 2008 report on the preliminary impacts of climate change in the Cariboo-Chilcotin

- 2009 Sustainability snapshot of the Fraser Basin: a good overview of the Fraser Basin as a whole

- The results of the 2012 Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of the Sockeye Salmon of the Fraser River

Recent News: